Amy Elkins’s Parting Words & Black is the Day, Black is the Night.

This week I spoke with Amy Elkins about her recent exhibition at Aperture Gallery and the two projects it included: Parting Words and Black is the Day, Black is the Night. Both explore issues surrounding capital punishment and her correspondence with male prisoners serving death-row sentences.

Liz Sales: Congratulations on a fantastic show!

Amy Elkins: Thank you!

LS: The exhibition comprised two bodies of work that you submitted to the Aperture Portfolio Prize?

AE: Yes, I submitted two bodies of work that are directly connected, and they selected me for both. They thought it would be more impactful to show them side by side. I couldn’t have been happier with the way it all turned out in that space.

Poem excerpts from a man who has been in prison since the age of 13. He was retried as an adult at 16 for attempting escape and was sentenced to life in solitary without possibility of parole at a super max prison. He has taught himself to write poetry over this time.

LS: Could you tell me a little about each?

AE: Black is the day, Black is the Night is a project that revolves around direct communication, through written letters, with seven men scattered around the country. Most of them were serving death row sentences; two of them were serving life for non-murder crimes committed as juveniles. At first, this was just a writing project. It slowly developed into an exploration of concepts surrounding isolation, memory, distance and time-passing.

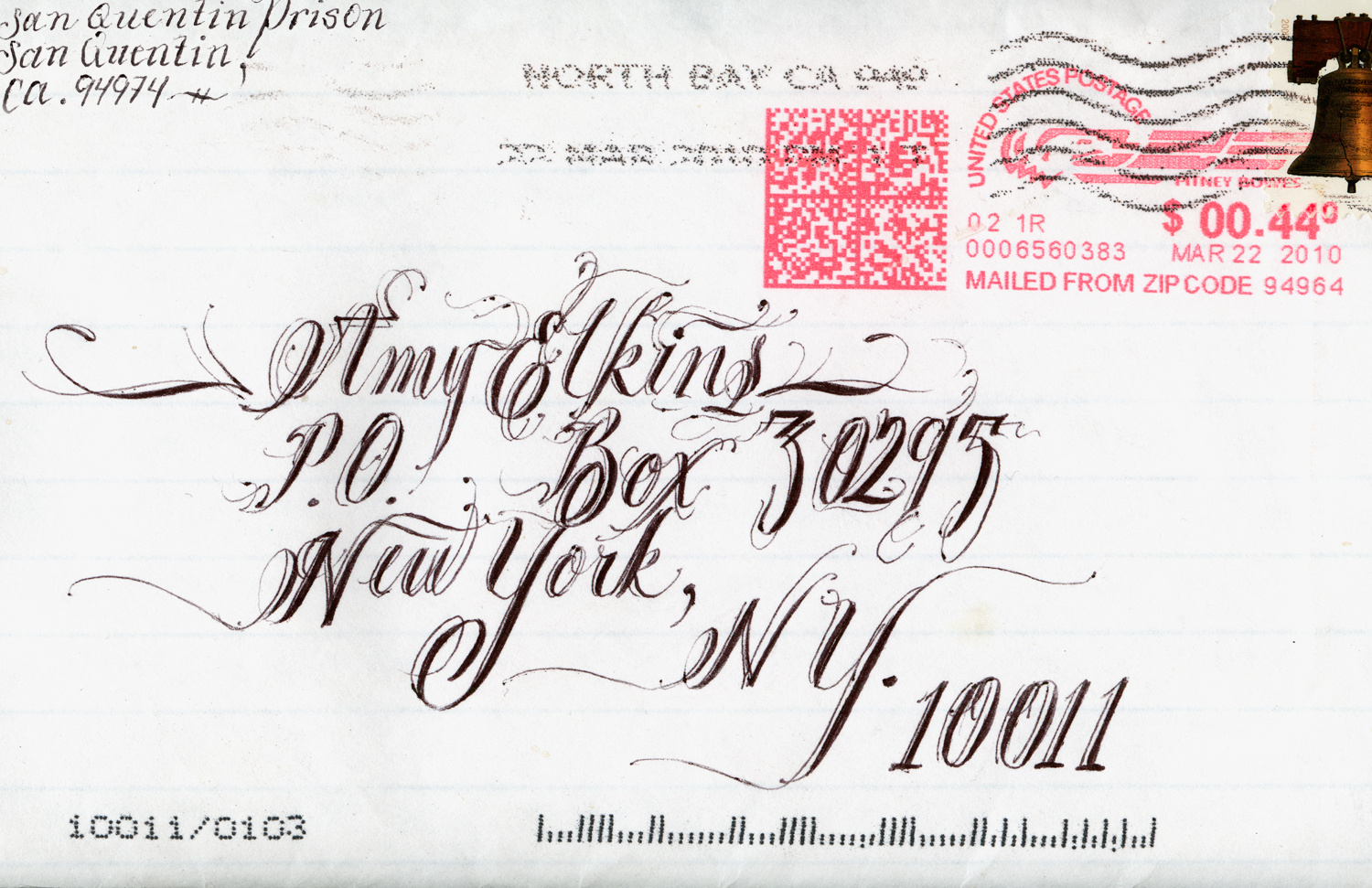

The project is made up of tangible pieces of evidence from our correspondence, like scattered letters, cards, returned mail and torn envelopes. It includes black on black text pieces that reflect the inaudible voice of a man who has been in solitary confinement most of his life— his words to me helped set the pace for the project. The remaining works are to me the most important. Portraits and landscapes created to reflect the time each man I penned with had served and how that time might have impacted their sense of self, others, memories and environments from their past.

LS: Right. The sublime capital “R” Romantic landscapes that are included in the show stood out to me. Could you talk a bit about how these images tie in to the rest of the work? They seem to echo the vast sense of isolation that might accompany incarceration.

AE: The landscapes are definitely meant to explore that vast sense of isolation, longing and loneliness of empty, open places. Early on in our correspondence, I had asked each of my pen pals a string of questions about what homesickness felt like, looked like, smelled like and sounded like. They were modeled after questions that a writer had asked me in regards to a show I was in years ago, and they made me really think about my roots. So each of them wrote back, and their answers were amazing, thought-out and full of regret and longing for a past they would most likely never see again.

Thirteen Years out of a Death Row Sentence (River)

A pen pal serving a death row sentence describes being baptized several years ago. The Father had to reach through the bars to touch him, even with such restrictions he remembers the touch as electric. Despite the act of the baptism he feared it wasn’t good enough to save him. He longed to do a full submersion baptism in a river, like Jesus had. This image was constructed out of his description of the river he wished to be baptized in using appropriated images which were then composited to account for the amount of years spent in prison.

I sought out imagery through google searches that echoed their descriptions and went from there. The first composite image I made was of the sky. I layered and layered the sourced material until I had as many layers as years he had spent in prison. Nineteen years, nineteen layers. It was made for a man who went into prison at the age of thirteen. He is now nearly forty years old and has spent over two decades in prison, primarily in solitary confinement. He was the first to write back about his homesickness, and his answers really struck me. His desire to see something as simple as the open sky stayed with me as it’s something most of us take for granted.

Nineteen Years out of a Life Sentence (Sky)

A pen pal serving a life w/o the possibility of parole sentence in a supermax prison (solitary) described being able to see the sky through a metal grated skylight in the small concrete exercise area he was permitted in alone for one hour a day. The additional 23 hours were spent in isolation. This image was constructed out of his description of the open sky he wished to see, using appropriated images which were then composited to account for the amount of years spent in prison.

Several other landscapes in the project were made out of descriptions given to me by the additional men I wrote with. All of which I found equally captivating, haunting, charged a river one wished to be baptised in, a forest once frequented as a child, a Texas death row inmates dying wish, a haunting memory of the ocean, a teenage hideout, the desert landscape.

LS: What was their take on the compiled images you made for them?

AE: They responded with a lot of intrigue and curiosity. Some decorated their cells with the images, and some seemed confused about what the images were, as if they were damaged in some way.

One response I loved getting, “I must admit to you that when I first received your letter two days ago I could not stop myself from feeling so overwhelmed by this longing of being in a place as lovely as that. I really do wish to convey my appreciation for [your] bringing these places to me right in my cell, where it makes my mind run wild.”

LS: That’s wonderful. As I understand it, of your original seven pen pals, one has been released, and two others have been executed. Could you talk a bit about how the lives and deaths of these men have affected you and your work?

AE: This is a question I could answer with pages upon pages. But to keep it short – the things that unfolded within my years of writing these men did take a hold of me in ways that I hadn’t foreseen. I was pretty blown away that within months of starting a project that looked to Capital punishment one of the seven men I wrote with was executed. Years later when the second man I wrote with was executed it hit much harder. We had several years of letter writing behind us and he had been fighting to the last minute with appeals in an attempt to save his life. It was the hardest part of the project for me and one I could in no way have anticipated. As for the man who was released, his letters started to taper off far before his release. In these letters, he seemed very eager to start his life again. We were in touch briefly after his release and it seemed he was doing great.

LS: You mentioned your roots. What is your relationship to incarceration? Where did your initial impulse to reach out to these intimates come from?

AE: I do have my own roots with the U.S. prison system. I’ve had several family members go in and out for various things, so it’s not something that is too abstract within my upbringing.

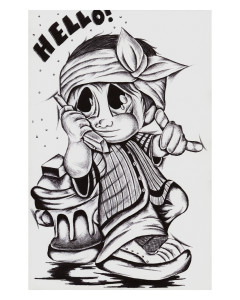

Ballpoint pen drawing on paper, folded into a card- sent from a then 33 year old man who has been in prison since the age of 13. He has been primarily in solitary confinement since the age of 16

Initially, I stumbled across this website for inmates seeking pen pals from various prisons around the country. It sparked my interest, but I had no project in mind. I was sort of haunted by that site for a while. I remember telling people about it. It made me feel really uncomfortable—this idea of clicking a button and finding thousands of men serving death-row sentences, all of them waiting for their execution to be carried out or fighting with appeals. I kept finding myself going back to that site and scrolling as if it were one of many social media sites we are all so drawn to. It felt very similar. The profiles were pretty basic, showing: age, location, religion, a profile picture, sometimes artwork. But below all of that, there were always links to their crimes and sentences.

LS: How and when did this project start to bridge the gap between life and art?

AE: It took me a few weeks, maybe even months, to decide what I wanted to do. I remember my boyfriend at the time warning me that it seemed exploitative to do a project about these men. I didn’t think so. I still don’t. I wanted to tell stories about men who have probably been forgotten and are far removed from everyday life, and that is what I attempted to do with BITDBITN. I have exhibited the work a little, but never in its entirely. The project is so dense I feel a book is the best way to share and get the stories out there. I have been working on getting one published and hope to have it out there in the world at some point.

LS: Your past work is concerned with our ideas of masculinity. This one seems to be as well. Why did you choose all male pen pals? What do you think is particular about the male experience of incarceration? How do you think this particular experience manifests in the work?

AE: Yes almost all of my work deals with masculinity and when I started this project I thought of it that way. The project of course became about so much more. But initially I wrote to several men in an effort to explore notions of hyper masculinity and their drive towards violence. What unfolded was so much deeper and poetic in scope. Rather than focusing on masculinity, we explored concepts that every human faces throughout various chapters of their lives: time, distance, memory, identity..

13/32 (Not the Man I Once Was)

Portrait of a man 13 years into his death row sentence, where the ratio of years spent in prison to years alive determined the level of image loss.

LS: I noticed that you use various visual strategies to obscure your imagery, like text, layering and manipulating photographs digitally according to the amount of time the inmate has been incarcerated. This could be read as a direct metaphor for incarceration, but I was wondering if it was also a response to the idea that the mug shot should be seen as a vestige of physiognomy because, in a way, by obscuring images of these men, you are returning your subject’s personhood.

AE: I thought of the various ways of obscuring as a fairly direct reflection of the memory collapse, imagination, notions of identity or identity loss, etc that couldn’t help but be muddled after being so far removed from the world. When thinking of how to approach making work about such concepts, it only seemed suited to completely obliterate, fabricate, construct or deconstruct the images in a calculated way. So each was distorted based off of direct sentences and ages of each man involved in the project.

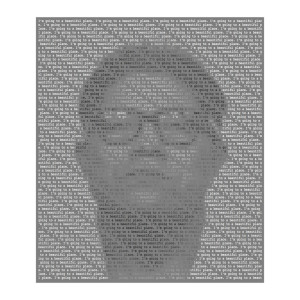

LS: Parting Words are mug shots of men executed in Texas, recreated with text and gradations so that they appear as recognizable portraits at a distance but dissolve into readable text—these prisoners’ last words—as the viewer approaches. Can you tell me a little bit about these works?

AE: Parting Words was actually an offshoot of BITDBITN. My first pen pal was executed three months after we started writing. He was in the state of Texas. When I went to find more about his execution on the Texas Dept. of Criminal Justice I found the other 400-plus men and women who had been executed, and my project was created out of that information—all provided by the state of Texas. Mug shots, last words, age, crime.

Ignacio Cuevas, execution #39, age 59

LS: What made you decide to incorporate the last words of executed men into your work?

AE: There was just something so damn haunting about being able to look up all of the prisoners who had been executed. It’s like reading an insanely mesmerizing novel that you can’t put down. You can start reading about the first man executed in 1982 and work your way all of the way to people executed last month, last week, yesterday. I would start by reading their last words, some of which were angry, haunting or non-existent. But some were just so heartbreaking. I would often feel compelled to read about their crimes. It took years to read through all of their last statements, make notes, dates, and pull quotes, etc because I had to work on this in small batches and take breaks often to keep from getting too worn out from the entire process. On top of that, just keeping the notes and dates, execution numbers, age, all organized. It was just a tremendous amount of work.

LS: It’s also layered and complex and very compelling. Thank so much for helping me unpack it.

AE: Thanks, I appreciate it.