Interview with Daniel Terna

Daniel Terna is a lens-based artist whose work is marked by absence. His images balance the emotional with the conceptual. We sat down with him to share food, drinks, and conversation shortly after the election.

Martha Naranjo Sandoval

Can you tell us a bit about yourself?

Daniel Terna

I’m the child of immigrants. My folks were not born in this country. Still, it sounds so strange to say that because I’m just a New Yorker.

Groana Melendez

Where are your parents from?

Daniel

Dad was born in Vienna in 1923 and grew up in Prague, which was at that time in Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic). Mom is also Jewish, Eastern European, but comes from Colombia. She was born in Paris after the War, but grew up in Bogotá. In 1959, when she was 12, her family moved to Brooklyn.

Martha

How did they meet?

Daniel

They met in a therapy group for children of Holocaust survivors. My dad is a survivor, and my mom is the daughter of survivors. At that time there was a movement around supporting first-generation children of survivors, exploring how they dealt with growing up in an environment where their parents were psychologically fucked up because of their experiences in the war. My dad was a speaker, and he saw my mom afterward on the train and asked her to get a cup of coffee. They got married three months later. She was 35, and he was in his late 50s.

Groana

How do you identify, especially since you’re adopted?

Daniel

I identify as an ethnically Colombian, culturally New York Jew. I have no cultural connection to Colombia. I identify a lot with being your typical over-analytical pseudo-intellectual New York Jew. The Colombian thing rarely comes up because nobody really knows or asks. Somebody today thought I was from Lebanon. My birth mother was from Bogotá, but I was born in Manhattan.

Martha

Have you been to Colombia?

Daniel

No. I started asking my mom for some information about my birth mom. Every time I think about it, I’m like, “I need to make this into an art project.” Then I get stuck, because I’m like, “I need to call the lawyer that was involved with the adoption.” Then I’m like, “Do I need to record the conversation? How do I record it? What kind of camera does it need to be? Can it be the computer camera, or can it be my iPhone? Do I need a setup? Do I have a camera on the lawyer’s end, so do I call beforehand to tell them that I’m going to call them?” Then I don’t do anything.

Martha

You just get caught up in technicalities?

Daniel

Which might just be an excuse not to want to open a can of worms. But I did start looking into it, and the crazy thing is the lawyer just died. So that’s another one of those things where I wonder, What if my birth mom died right now? Maybe she’s in Queens; maybe she’s in Bogotá. What if I just missed that by a day? How awful would that be? Because I spent the last two years thinking about doing it, and then I didn’t do it, and then I did it, and now she’s dead.

Groana

Stop!

Daniel

It’s so Jewish. It’s very Jewish, that sort of anxiety, like worrying so much you don’t get anywhere. You’re standing in one place. You’re just standing in one place worrying.

Martha

Like a Woody Allen character.

Daniel

Like a Woody Allen character. Yeah. But I’ll do it. Don’t worry. I’ll do it somehow, but what if I have siblings? It’s weird. I probably do have siblings.

Martha

You don’t know what’s waiting for you on the other side.

Daniel

No, I don’t. Every Colombian I meet is like, “You have to go to Colombia, it’s awesome, I’ll tell you where to stay.” I have a standing invitation at an artist-residency in Medellín.

Martha

I get the hesitation, though, because you don’t know what’s waiting for you and it’s easy just to guess instead of confronting it.

Daniel

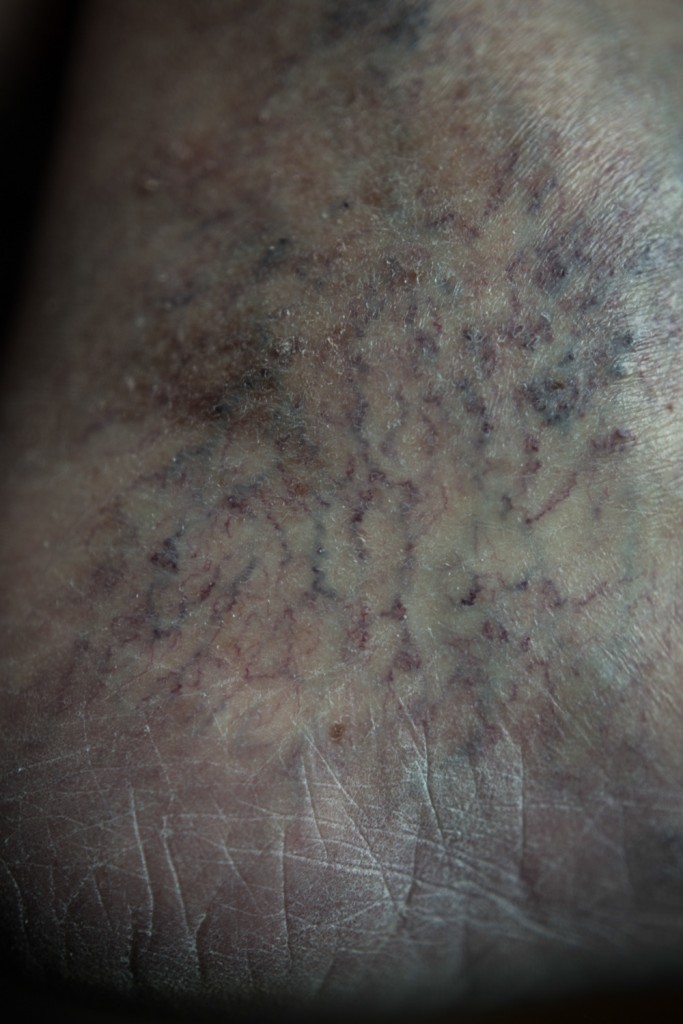

My dad says that I should use his story and experience in my art. He’s like, “It’s a very special situation that you still have access to a Holocaust survivor, and you should use me as much as you can.” With these newer pictures of his skin, I’m doing exactly that: looking closely at his body.

Groana

It sounds like a collaboration because he’s urging you to tell his story.

Daniel

I don’t know if I would call it collaboration. I’ve collaborated with another artist, and it’s a very different experience. With this, he’s more game to do stuff, but I don’t know if he would call it collaborating because he’s more like, “Do your thing. I’m here for you, and if you want to do this idea with me, great.” I use his body and the objects in his studio and his paintings as props, but there isn’t an active conversation going on.

Martha

In our classes at ICP there were a lot of people working with family. It’s interesting.

Daniel

For me, it comes from a fear of his death and wanting to go to places emotionally that we just wouldn’t under any normal circumstances. My father’s long life and his eventual death is the elephant in the room. He says that with his first wife, who was also a survivor, the Holocaust was the elephant at the dinner table. Through my pictures and my work, I have a portrait of my dad, and if I have kids I can say, “This was your grandpa. This guy.”

I’ve always had a fear of his death and anxiety about losing him. I grew up knowing that he was old and that he would die when I was young, so I’ve always been preparing for it. But he’s 93 now and very active and healthy. I think many of us photographers want to make work about our families. I think we’re all trying to understand ourselves better.

Martha

For me it’s not about death, but rather memory as it relates to personal history. Both my parents are orphans, but they are very young, so I never associated them with mortality. It makes sense that you have a closer relationship with death.

Daniel

My dad is an artist, and he paints because the paintings are going to outlast him. His art is a record of his survival. He paints with acrylic because it lasts longer than oil or he covers it with a veneer after he’s done painting so it’s damage-resistant. When people come to look at his paintings, he starts scratching them. He’s like, “See? Nothing is happening. They’re good. They’re going to outlast you; they’re going to outlast your grandkids. If you’re going to spend money on this, it’s going to be made well.” I think a lot of that is his personality, but I also think it’s interesting to think about it as his desire to make a little mark on history. His paintings are essentially documents of him, portraits of his psychological state.

I started taking pictures of his skin and his wrinkles because I was interested in texture. His paintings are very textured as well; he uses sand and pebbles. He wants blind people to be able to see them. When you look at them you can see light and shadow; I wanted to do that with his skin. I wanted his skin to be my canvas. I wanted to make pictures that could relate to that physical sensation. I don’t know if I succeeded, but they’re not bad pictures.

Technically, I had been shooting with a flash, and that work was beginning to blend with some of my commercial work. It started to go in a direction that a lot of other people were headed, so I started thinking of the assignment Nayland Blake gave of breaking your own rules or setting boundaries. I decided not to use a flash. I put all these magnifying lenses on the camera so I could get really close. I also wanted to make something that was about going back to the beauty of optics, which to me meant using natural light, really soft focus, and doing something that wasn’t so trendy.

Martha

When I saw them, it was not what I remembered from your show or from what I know about you. It was very interesting.

Daniel

Yeah, it looks different from what I had been doing.

Martha

Also, you don’t want to get into the trap of yourself.

Daniel

Exactly. I wanted to break it up, to try not to have a visual style—or even a style of personality. Sometimes I can be really depressing and sometimes I can be, in my opinion, hilarious. I have a huge variety of interests and approaches, which is sometimes to my detriment. While there are recurring themes of isolation, absence, labor, my relationships to others and specific sites, I don’t think my work is identifiable by a specific visual style. Sure there are strategies I use myself because they’ve worked for me in the past and I have a lot of trust and confidence in the instincts I’ve sharpened over the years, but I can’t entirely say that everything I do looks like it was done by me, Daniel Terna. I could see myself having a solo show and someone thinking it’s a group show.

Martha

Sometimes the story wants to be told a certain way.

Groana

When did your dad become a painter, and did you get into the arts because of his work?

Daniel

My dad started drawing in the concentration camps. One of the first camps he was in was Terezin, in Czechoslovakia. Terezin was a gated fortress concentration camp, but by most standards of the time, it was not so bad. There was a degree of freedom of movement so that Jews could congregate. Terezin was a hub of intellectuals, so there were a lot of famous painters, musicians, composers, singers—all kinds of artists. They got together and had these sessions and even informally taught those who would listen, like my dad, who had been taken out of school.

He became interested in the arts. He was like, “Okay. I want to be an intellectual. I want to be involved with this kind of community and live my life (if I survive) like this.” That’s where he got exposed to some artists that were drawing on paper, what little they could find. When he was in some of the worst camps later on (Auschwitz and later Dachau), he drew with a twig in the dirt. If a Nazi walked by, my dad could easily erase what he had made. He was teaching himself. After being liberated in 1945, he went back to Prague and discovered that his father, brother, and everyone he knew had been murdered in the camps. He married his first wife Stella, whom I made a film about (My First Wife Stella), and in 1946, he went to Paris and started taking a few art classes there, sketching and painting. He’s been doing it for his whole life.

But I didn’t get into the arts because he’s a painter. I was into photojournalism, especially war photojournalism. I always looked at the names of photojournalists in the New York Times, and I wanted to be just like them. I wanted to photograph in Afghanistan or Iraq when the wars broke out. In high school, I started taking pictures. The first things I shot were the Jews in Borough Park. I just wandered into buildings and businesses and openly photographed them.

Martha and Groana

Then what happened?

Daniel

I went to Bard, and I started seeing fine art photography, and that started shifting my perspective. I started reading Susan Sontag and learning about the problems with photojournalism, and I realized that what I really wanted was danger. I wanted the adrenaline rush, but I didn’t care enough about making pictures of people in trouble and telling the world about them. I didn’t care about doing that myself. Pornography is a really strong word, but I see some photojournalism as this twisted form of media entertainment.

I realized I couldn’t do it. An adrenaline rush was the wrong reason to be a photojournalist in a war zone. I took a class with photographer Gilles Peress at Bard, a human rights class, and I told him I was interested in being a war correspondent. He sat me down and said, very seriously, “I’ve lost a lot of students to war, who wanted to go to war, who got killed, and you will get killed if you go to war.” I laughed, and as a result, he body-checked me. He lifted me up and threw me to the ground. This was in front of some people, but it was really intense, and I was like, “He’s not kidding.” It was a supremely bold statement on his part, and it really cemented what he meant. He’s an incredible person, a true intellectual and deeply affected by the wars he’s photographed and the Rwandan genocide. I still see him around Fort Greene.

Groana

Why didn’t you end up in a journalism school instead of Bard?

Daniel

I did journalism in high school, and I loved journalism, and I still love journalism. One of the reasons I love photography is because you go into these unknown places. I think that’s why a lot of us are photographers. You have your camera, and you just go. Especially if you’re younger, you’re like, “Okay. I’m just going to go explore with this camera.” You discover people’s stories and talk to people, and sometimes even pretend to be someone you’re not, which is what I did a lot of times. I looked at colleges for journalism. I was looking at Boston University because I thought maybe I would be a reporter. But then I went to Bard, and I studied art history and photography, and the photo program was so intense that I ended up really dedicating myself to it. I also worked on the school paper, the Bard Free Press, eventually becoming the Editor-in-Chief, which is something I’m really proud of.

One of my photography teachers was An-My Lê. She photographs with a view camera, but she works within fast-paced worlds, such as army bases, the military in training, even shoots on aircraft carriers. She works with subject matter that a photojournalist might be interested in, but she doesn’t approach it in the way that a photojournalist would—with an SLR, shooting a lot of frames. She takes many steps back and is like, “I’m making landscapes and pictures of huge systems.” I loved how she perceived the world, instead of documenting up-close the pain of others, which is this endless conversation we can have over and over. Every time you see a picture of a dead Syrian child washed up on a beach, and say, “This is a powerful picture. This picture will get the world to change, to get off their asses and fix the refugee crisis.”

That conversation is always happening, and it doesn’t seem to stop, but it doesn’t seem to help enough. I have faith in the new power of virtual reality, like Clouds Over Sidra, where they made a documentary in a refugee camp. They set up a VR camera inside a tent. You see groups of kids walking right past you, and it’s like you can touch them. You’re there, and it’s so effective. It’s a really intimate picture of a situation in the world that is hard for us to imagine ourselves. It’s been really amazing as a technology.

I would love to use that kind of technology with my dad. For my thesis, I put a GoPro on him. The idea was to get the viewer to be in this old body that was moving on the stairs, and I was trying to think of a way I could relate his trauma and his survival to people, and I don’t know if I accomplished that. I don’t think I dug into it deep enough. After I did that, you started seeing this VR stuff coming out. I would like to do things with my dad with that kind of technology. What is it like to be a 93-year-old taking a shower, cutting your toenails, eating, just being in your body.

Groana

You still wouldn’t get to the experience of being. You would be watching him. So it would be more visual porn.

Daniel

Yeah, but you could also do this GoPro kind of thing with VR, in a way. You could. I don’t think you could feel exactly what old age is like, but that shouldn’t limit one from trying it. I thought, “How can you make somebody feel a physical sensation by looking at a photograph?” I tried to do that with some of my photography early on in grad school, and I don’t know if I failed or succeeded, but I was thinking about when I used to go fishing. I remembered the feeling of the fishing line on my finger. Or if you ever played the piano, the memory is so intense that you can almost feel it on your skin. You could feel the weight of the keys or the feeling of the fishing line, so I had my dad put on his socks, or tie his shoe, or comb his hair and brush his teeth.

Martha

How did you start 321 Gallery?

Daniel

The gallery started with my buddy Mekko Harjo. We wanted to show our work, but we knew it was impossible to be noticed by any galleries. It was 2012, which is actually not that long ago, but it feels like an eternity. We put up a show. Then I did a second show a year later. Two of the artists who were in that show, Tin Nguyen and Tom Forkin, asked if I wanted to team up and convert the space into a functioning gallery that mounted shows more frequently. I said yes.

Now Tom and I are working constantly at the gallery, helping people realize their projects. We’ve done 22 shows, including three art fairs. Well, we’re about to go to our third art fair, NADA Miami. Which is a ludicrous thing to think about in comparison to the election.

Shifting away from the gallery, I’ve been thinking that all these Trump supporters have identities, and I wonder who they are. It’s the first time that I felt the liberals were almost mean and overlooking a huge amount of people, especially when Hillary said, “A basket of deplorables.”

That kind of rhetoric is so offensive, and people knew that it was offensive then, but now we’re sitting here thinking, “Oh, my God, we’re fucked.” Who are we to sit on our overeducated chairs and judge a lot of white people in America who are not as educated and have been barely scraping by? When I go to D.C. in January, I want to see who these people are. Even saying, “these people” sounds so fucked up.

Martha

Of course they’re not all in the same.

Daniel

No, of course not. Also, can you blame them for being pissed off? It’s a weird position to be in. When Eric Garner was killed, I saw this moment that photography was about to have. Charlotte Cotton had just made Photography Is Magic, and she closed the book on that way of making work. And in a way, I’m thankful that conversation has died down. I need a long break from it. For what seemed a long time we were seeing the kind of work that Charlotte Cotton was really putting on this pedestal. I don’t give a fuck about that shit at all right now. It makes me angry to think of making work about the medium, photography about photography. It’s like when Daft Punk comes out with a new summer hit that gets overplayed everywhere. It’s exciting for a week, and then you just want to turn it off or leave the room.

When Garner was killed, I thought we were going to see a lot of work about people, and humanity, and emotional subject matter. I thought my interest in photojournalism and the problems I had with it would coalesce into something. We’re seeing work being celebrated now by artists who have been making socially-concerned work but were overlooked for a while.

I think this election has woken up all of us, and that includes artists. I haven’t seen energy like this since 2003 when the war in Iraq started.

Groana

What are you working on now?

I’m still working on the skin and canvas idea, and playing around with masks and theatrical setups with my dad and sometimes my mom. Meanwhile, I’m working with an amazing designer, Rory King, finishing the publication of my From Several Angles Over Several Days project, which I first showed as a photo installation at Baxter St. at CCNY in the 2015 juried show. I’m also helping my dad curate a large show of his paintings at St. Francis College in Brooklyn Heights, opening in January. And most recently I began giving him these assignments to make political paintings, and photography will be incorporated into it. Definitely a new, unusual direction for both of us, but something to do in reaction to the current climate.

Daniel Terna (b. Brooklyn, NY) has participated in select group exhibitions at MoMA PS1 (NYC); the International Center of Photography (NYC); Foley Gallery (NYC); Baxter St. Camera Club of NY (NYC); New Wight Biennial (UCLA, Los Angeles); BRIC Arts Media Biennial (Brooklyn, NY); New York Film Festival (NYC); Eyebeam (NYC); Museum of the City of New York (NYC); The Wild Project (NYC); the Carpenter Center for Visual Arts (Cambridge, MA); Armory Center for the Arts (Pasadena, CA); Contemporary Arts Center (New Orleans, LA); and Gallery Tayuta (Tokyo, JP). Terna was a resident in the Collaborative Fellowship Program at UnionDocs, Brooklyn, and was awarded the Cuts and Burns Residency at Outpost Artist Resources in Ridgewood, NY. Terna graduated with a BA in photography from Bard College and received his MFA from the International Center of Photography-Bard. He runs and co-curates 321 Gallery, Brooklyn.