Interview with Andrea Wolf

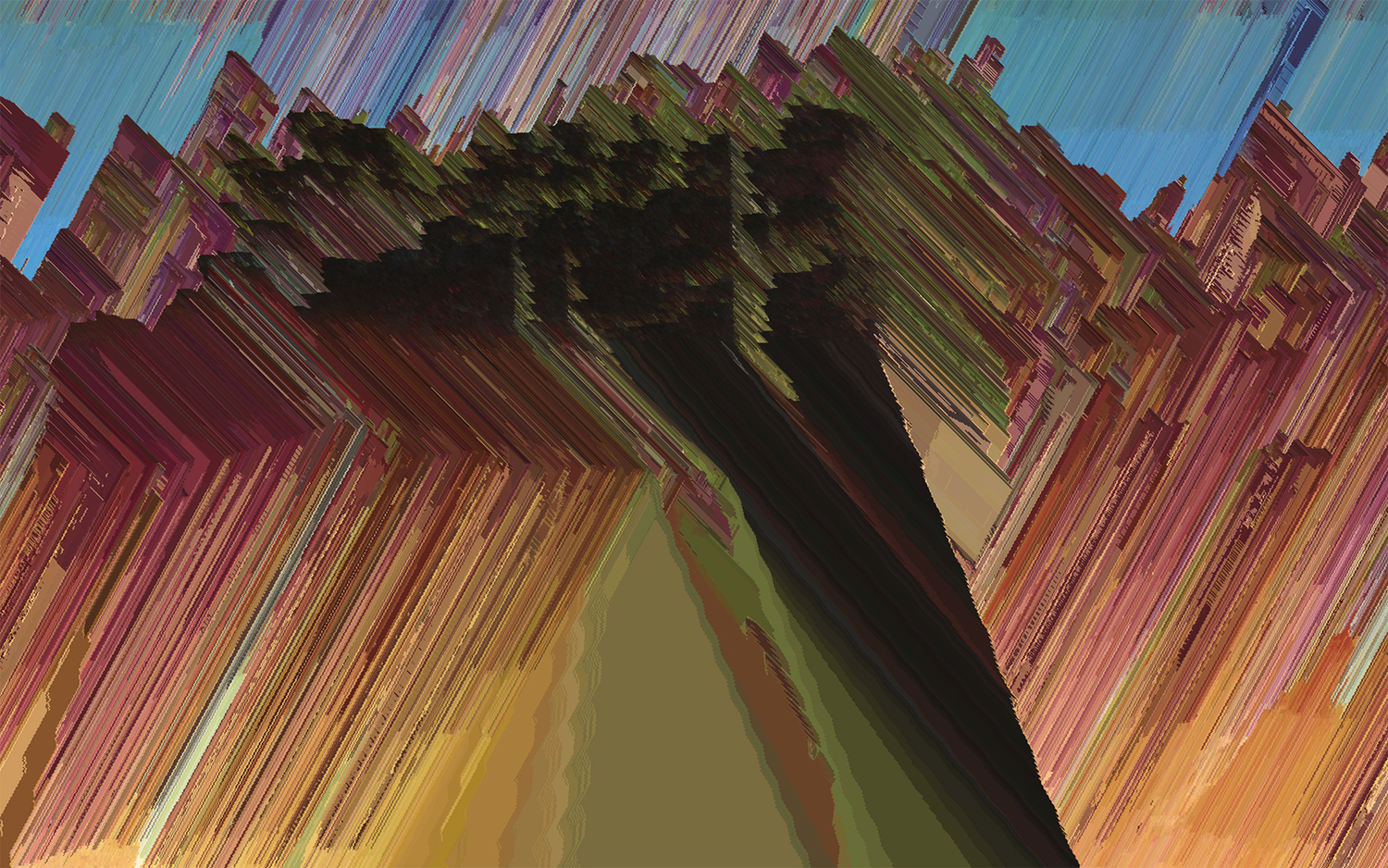

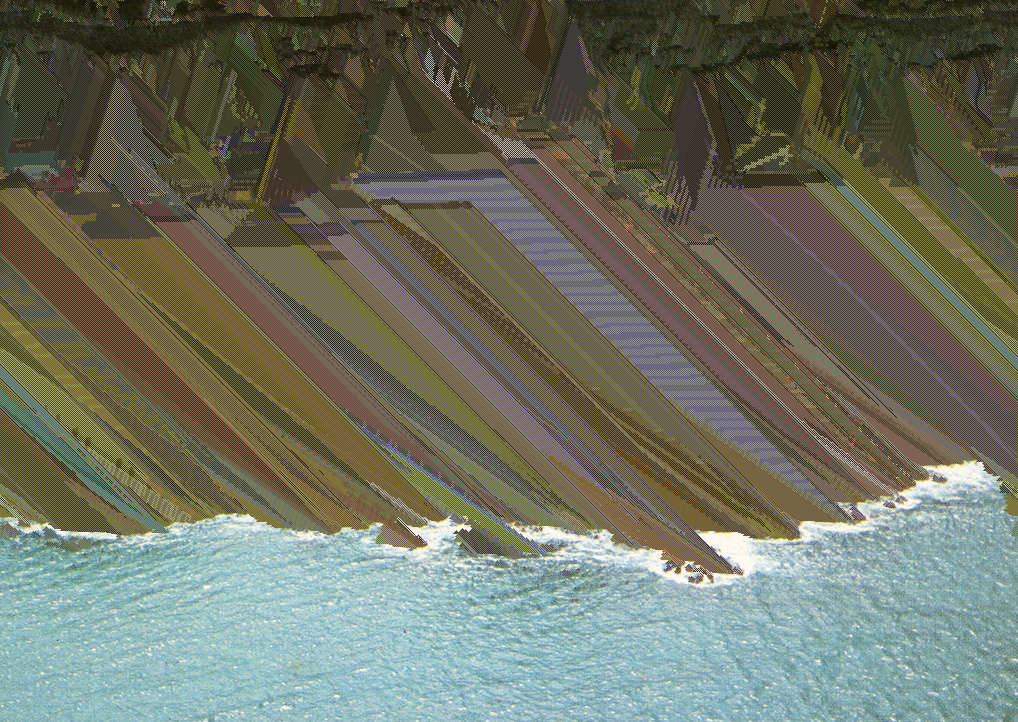

Andrea Wolf is an interdisciplinary artist interested in how images accrue meaning culturally. Her project Weather Has Been Nice uses algorithms to decompose images taken from mailed postcards.

Martha Naranjo Sandoval

We’re going to talk about a couple things, but let’s begin with Weather Has Been Nice. How did you start this project?

Andrea Wolf

About three years ago I discovered an open source pixel-sorting sketch and processing by Kim Asendorf, but it was only for still images. I liked how the pixels shifted, distorting the original image and also endowing it with movement. I was also curating a show for Miami Basel that focused on landscape and technology. Those two things started to merge, and I thought it was a very interesting way to explore landscape by decomposing it. Memory is a very important aspect of my work. I already had a few postcards, but I wasn’t into collecting them yet. Then things just started to click. I had the idea of working with landscapes and I had these postcards that show idealized scenarios which connects with the discourse of tourism and the question of what you are supposed to remember. Decomposing these images shows that landscape as memory is not only something outside ourselves, but also a construction. It’s a personal construct and a social construct.

Martha

I was thinking about all that needs to happen to these postcards before they arrive to you. The photo been taken, the postcard been designed and printed, then been bought and written on and sent. Then someone else receiving it and then discarding it, and then you finding it and scanning it and turning it into something else.

Andrea

In general I like working with found footage and appropriation. I share that feeling about the story of these objects. Things that are so personal end up in flea markets or junk shops. I’ve always thought it would be very interesting to document the history of even just one postcard. But that’s another project entirely.

I decided to work only with written and mailed postcards. When I began collecting postcards, I needed a restriction; a criteria of selection. There might be aesthetic criteria too, they had to be in color, and I was specifically looking for landscapes because I was trying to explore them visually. Then the fact that they had been written and mailed became really interesting. I’m fascinated with the social and the personal; the relationship between personal memory and cultural practices of remembrance. I had to consider how to make this more evident in the pieces themselves, But I didn’t want it to be something very explicit. Finally I came up with the idea of inviting different sound artists and sound poets to create soundscapes with those texts.

Weather Has Been Nice. Sala de arte CCU, Santiago Chile, 2016.

Martha

This project has gone through several iterations. Every time you show it, you want to bring something else to the table. It’s not a closed project; it feels like an evolution. How did you decide to be so open?

Andrea

It wasn’t a conscious decision. The media I work with lends itself to this kind of progression. Also, making one piece requires so much work and production, and after I show it I start to think about what else I could do, or what I could do differently.

I’m comfortable thinking of my work like an open-ended series. It’s more complicated in terms of a commercial point and determining how to sell the work, but by showing different versions you also see it grow progressively.

I think the installation for Weather Has Been Nice, as it was presented at NEW INC’s Showcase at the New Museum and then at Sala de Arte CCU in Chile is at its peak. Those where large-scale installation but now I’m thinking of producing smaller, individual pieces for each postcard,

I have a show coming out next year in a gallery in Chile that is a different context for showing this project. I have the idea of making individual pieces for each postcard, and then also the idea of making prints and flipbooks. There are so many things that I can do, particularly with this project. If I continue finding more postcards and scanning them, why would I limit it? Why would I say “No, it’s done”? No one is telling me it has to be done. If there’s a point where I feel like I have to move on, I will.

Groana Melendez

I work mostly in photography, and I can keep going because it’s my family and my family keeps growing. But it’s nice to hear you talk about a different kind of process and still being open-ended because in the end, everything you do is part of your practice.

Andrea

It’s open-ended, but it’s also limited. You establish some rules or some common practices for a specific work or series to develop. It’s not that suddenly I’m bringing in portrait postcards. It has a line. It has a path. I’m sure it’s the same with your photography practice.

You trace borders and frontiers, and some of them you can push, which is also interesting. Some of the most interesting things in the work happen by mistake –for example, I might be projecting something and I see the reflection on the floor and I wasn’t looking for that, but it looks great and maybe that is the thing.

I think it’s a disservice to you and your work and your practice to limit yourself. On the other hand, it’s important to work within certain ethics and logic and specifications for each project.

Martha

What I really like about this project is that we usually think of moving image as the progression of different images, twenty-four images per second. What happens in Weather has been Nice is not that, but it’s still moving image. It blew my mind when I realized that instead of being a video in the common sense it was an algorithm that in real time was affecting a still image. I like how it subverts what moving-image can be.

Andrea

When I started, I wasn’t aware that I was subverting what we understand as moving image. I was interested in unraveling or unfolding an image. I was reading a really cool book by Bill Viola, Reasons for Knocking on An Empty House. It’s essays and his writings. It’s kind of like an artist’s sketchbook.

One of the essays resonated a lot with me. It was about how HD image has prompted this obsession with being very realistic, with high fidelity and getting sharper and sharper, and at the end of the day that’s not necessarily the most real image. If you only give image the value of a mimetic representation, then maybe it is, but what does an image really is when you think about the real image?

An in this essay he writes, “to search for the image that is not an image, not a realistic rendering, but an artifact. ” That resonated and stuck with me. In many ways that’s what I think about memory and that’s what I think about the images of ourselves and of the world that we put out there, so I just wanted to question our methods of representation and the value we bestow on images. I mean, this is a super real image of a landscape when it’s kind of unfolding before your eyes. Also, we have this need to create logic out of what we see, even if it becomes very abstract and with geometrical shapes, a lot of people still see a landscape in the abstracted version of the first initial image.

Martha

I also wanted to talk a little about REVERSE and how it influenced your practice to be in charge of this huge project for so many years. [REVERSE is a non-profit artist-run organization dedicated to expand the conversation in Art and Technology].

Andrea

In many ways it was a great experience. It made me more aware of my administrative counterparts when I’m an artist, and helped me understand the expectations of a gallery or an organization—like the importance of meeting deadlines and sending images when you’re asked for them. When I was running REVERSE I couldn’t understand why I had to go after artists to get their images for a press release.

It also helped me be more organized in general. At the beginning REVERSE took away from my practice. Preparing the space and figuring out how it should work consumed so much time and energy. But it also allowed me to engage with a much broader artist community than I would have just working in my studio by myself. My network grew so much, and not just visual artists, but sound artists and curators and organizations doing similar things.

It put me in a position where I knew more people and also had to look for more people. If you’re curating a show, it takes you away from your regular group, your social connections, and your comfort zone. It opened a lot of new opportunities for me to learn, to see, to rethink my work. I saw so many performances and different artists and works going through the gallery and that clearly influenced the way I was thinking about my work.

Even though REVERSE took some time away from my main studio practice, I had a privileged seat in watching a lot of different artists who were in a similar point in their careers as I was, and maybe a few who were further along and a few who were just starting out. It gave me a lot of inspiration and information.

Martha

How did it all start?

Andrea

It was like a real estate marriage. I had this idea of how cool and interesting it would be to have an art space with art studios, and a gallery and build a community. I had a vision of a place where I would like to work and be as an artist, but I wasn’t actively looking to make it happen. If I had planned it better I probably would have gotten a few partners.

I had to leave my apartment because they were raising the rent and it just didn’t make sense for me to stay there. I lived in Williamsburg, near REVERSE. One day I saw that a really cool spot—a garage in a great location, that now has been turned into a fancy restaurant— was available for rent. I wasn’t looking for a commercial space, but I like real estate porn, so I called.

I met with the broker, and I was like, “This is cool, but I actually need an apartment.” So he showed me another place a block away. It was crazy: upstairs there was the apartment, and downstairs it was this small warehouse open space. I can be very impulsive, and I got super excited. I talked with the friends I was planning to live with about the upstairs situation. I also have a good friend who works in construction, and maybe two or three weeks before this we had been talking about the idea of having a space. He said, “If you ever do that I’ll help you build it up.” He had done that with other spaces. I called him and I was like, “Piro, remember our conversation? I think it’s happening.”

A lot of things just came together. I had very good friends who supported me. It sounded like a great idea to live there and have the space. I already knew enough curators and artists. I had been showing as an artist. I had the community from ITP. I knew that I could put the word out there and that to kickstart it I would invite curators to guest-curate.

I had my business plan to build walls in the larger space and create studios to rent out to artists, which would help sustain part of the space. I didn’t anticipate the amount of work involved in not only building it, but also managing it. So I just jumped in and went for it, and it grew like a monster.

I try to be a little bit more conscious in my decisions now. It was great, but maybe it’s better to think things a little bit more through. On the other hand, if I had thought it through more I might not have done it. I think that at some points in your life you have to take those leaps of faith and go for things, but I’m older and more tired now.

REVERSE Art Space.

Martha

It was a great space. It also reminds me of what you’re saying about your work. You had limits. It was meant for a special kind of art that might have had a hard time finding a home.

Andrea

That was definitely one of the missions. I didn’t want to limit REVERSE to new media or art working with technology, but it became super clear that that was a common thread. It was very natural because of my art practice, and because of the people I know and my ability to understand work that other places might have turned away. I was very happy to push it in that direction. But we established that it was more a conversation about technology than technology was a requirement for every exhibition. For example, we could have exhibitions about painting and architecture. This idea of being interdisciplinary and trying to understand how technology affects us as a society, culturally, and also how it affects the art-making process. A lot of people working with art and technology came to us because we were one of the places offering a space for it.

Groana

A lot of the things you said about managing REVERSE reminds me of us [Martha and Groana] working together right now.

Martha

I think we get carried away by thinking, “It would be awesome to do this.” Then when we’re doing it, it’s like, “Oh, this was so much more work than we thought it’d be.” It is not only curating the list of artists, but reaching out, researching, coming up with an interview strategy, then meeting up, recording, editing the recording, transcribing, editing the interview, reaching out again with the artists, picking the images…

Groana

Any words of wisdom?

Andrea

My advice is, don’t think about all the work that’s involved; just follow through. Woody Allen says that comedy is tragedy plus time. We tend to forget because if we didn’t, we wouldn’t do anything. Imagine if you remembered how terrible you felt during pregnancy or how difficult birth was—no one would have more than one child.

These are things that you learn. Then for the next big project you might be able to set boundaries a little better because you will know how much you can do. And—this is very important—you have to learn to listen to yourself about how much you want to do.

I also learned that sometimes you have to invest to make good things good and to achieve the outcome that will eventually get you the financing you need. I also value my time. It’s important to put a price on your time. Like, how many other things could I be doing while I’m transcribing that would get me further toward my goals? Where should I put most of my effort? Is it really in transcribing or is it in editing the interviews and diagramming the book and thinking of all of it together? Of course we are limited by our resources, but sometimes you have to invest a little in order to get much more out of it.

I had to make a decision. I couldn’t continue with REVERSE and have my practice. I had to decide which one was more important for me, and which one to push forward. I chose my practice, because for me REVERSE was like a super big art project. I didn’t want to be a gallerist first and foremost and an artist on the side.

So, my advice is to push through. You’re already in it, so make the best out of it. And think of all the good things you will get out of it. Not only in what you make or what you accomplish, but in having interesting conversations with different artists.

Martha

You’re right.

Andrea

It wasn’t easy to learn all this. Believe me. I probably still don’t apply everything I’ve learned.

Martha

This project was born out of a studio visit. I met with a curator, and he told me that my art was not Latin American enough for his show. I said, “What is that? What does that mean?” Then Groana and I decided to showcase Latin American artists to explain how so-called Latin American art is not a thing.

Andrea

I think that goes in line with an older view of Latin American art. It’s someone that has an image of Guayasamín, the painter from Ecuador, or, very political art. I think that’s still part of it, but nowadays the boundaries are so much more blurred. My art would probably not be Latin American at all for that curator.

It’s very important to consider what it means to be an artist from Latin America. How much does that really define you or your art? What does it mean to be an artist from Latin America in New York? I can see how that could be an easier place to situate yourself because there’s a specific market for it.

I have a lot of issues with paperwork that asks you to define yourself and your identity. I’m from Latin America, but I’m also Caucasian and I’m also Jewish and my grandparents are from Eastern Europe, so what do I mark? It’s great when you can check more than one box, but it’s a very limited view of what a person is. I can’t help but think of Deleuze and Guattari and El Devenir [Becoming]. This idea of identity as something that is constantly transforming. I understand we won’t get bureaucracy to see it that way.

It still feels very binary, and I think the world in general is moving to a different place. I wouldn’t know what to tell that curator. Maybe he should visit more studios of artists from Latin America and see what they’re doing. Maybe his opinion will change. I would like to have a definition by his standards. I bet it’s very political or ethnic.

Martha

I don’t think there’s a degree of how Latin American you can be. I think that whatever I do just because I am Mexican, it’s Latin American art. We were really upset. That’s why we’re starting this, because I think there’s a way of defining what’s not you in terms that feel comfortable to you.

Andrea

I know a little bit of your work. You work a lot with your family photos, and they’re not photos from a typical midwestern American family. People think that if you’re from Latin America, you can’t be blonde or have very light skin. And there is an expectation that Latin American art will be related to crafts. It’s very ignorant—not only about the current state of affairs, but also about history. The Spanish, the Portuguese, the Italian, the French, the English all came to Latin America and grabbed their piece. At some point there was a mixture, and something different will come from that. I’m getting upset.

Martha

When it first happened, I was very upset. It’s hard to respond to something like that. I know it’s unlikely that anything I’m going to say will change anyone’s mind. But his comment empowered us.

Andrea

That’s great. And I understand the feeling of not knowing what to say in the moment. I would probably ask the person to define Latin American art—not to correct him, but just to know what he thinks. C’est la vie. That’s too French.

Groana

It’s not Latin American enough.

Andrea

Yeah.

Groana

Tell us how you got into art, how you became an artist.

Andrea

I actually studied journalism and communications back in Chile, and people in Chile tend to make a big point of it, like, “Oh, she’s a journalist and an artist.” I’m like, “I’m not a journalist. I don’t work as a journalist. Yes, I studied that and it’s not like I’m denying it, but just because I went to college and got that degree doesn’t make me that.” I worked in all type of media while I was studying and I came to the realization very early on that I didn’t like journalism, but I liked documentary films.

I always liked working with research and nonfiction material. I did my last semester in Barcelona and I loved it. I saw that they had a master’s in documentary filmmaking so I went back to Chile to graduate and then went back to Barcelona to study documentary filmmaking.

I liked more the theory classes than the actual practice just because they were going through all the subjects that I’m really interested in: the meaning we give to images, specially as an index of truth, cultural visual operations, and collective memory and storytelling. So I got very excited about all that and then… – I’m taking the long road to answer this, but it’s just that it wasn’t like a specific moment when I was like, “I’m an artist”.

I actually wanted to stay in Barcelona and it was much easier to stay as a student and it wasn’t as expensive as it is here to study, so I enrolled in this Masters of Digital Art because I loved editing and video and I saw a lot of classes there that I thought could be helpful in my practice. I had classes of programming, this is going to show how old I am because our classes, I think it was the last year that they taught programming with Action Script, but we also had Pure Data and stuff like that. And, oh my god, did I suffer at the beginning. I was like, “What the hell am I doing here?” I never saw myself as a technical person. With video, yes, that came super natural to me. Editing, I loved it.

Then after the first month of being like “What am I doing here? What is this?” I started making peace with it and I saw the amount of opportunities that open up when you are able to control the tools to create the work that you want to do. Not that I’m a great programmer, but that was something that interested me. And when I started working on my thesis project with another friend, an artist, it proved to be useful. It was the first time that I actually started using home movies and we programmed this whole project.

It just was this kind of natural progression that took a while to settle and understand. I was still thinking “I’m going to do documentary film”. I’ve always been very interested in film in general, so I didn’t see that right away, but things just kept taking me back to thinking of film even in a different way and not as a movie that you have to watch in a theater.

Then for different personal reasons I had to go back to Chile. I had this online project that was memoryFrames and I showed it to some people that were working with art and technology and they invited me to join an exhibition that they were curating, but I needed a physical interface and I had this idea of a machine that would emulate the metaphor that we were doing on the online version, but I had nothing done. I had a month to build that. It was kind of horrible, but also great. There was a moment when I was in Chile that I had to find my place that I realized that was what I wanted to do and that I had to start reaching out to the community of people working with Art and technology.

There was this one time that I met this very well established artist in Chile with a long trajectory. Again, he thought I was a journalist because the person who introduced us told him that. We started talking and he was like “Oh, but you’re not like interested in doing an interview. You’re an artist.” That was the first time that I had to say, “Yes, I’m an artist.” It takes a while to feel comfortable with that statement – years. But at some point being in Chile I said “Okay, this is what I want to do and this is where I have to put my energy.” Things started happening and exhibitions started to pop-up and then I applied to the Interactive Telecommunications Program at Tisch, NYU. The only program that I applied to was ITP. I got accepted. I got a scholarship from NYU.

I came here and at some point I felt the same that I felt with the Master’s in Digital Arts in Barcelona. I was like “What the hell. This is so much technology.” I just don’t like technology for the sake of technology, I only like it if it allows me to say something. Here I am now. I can’t shake it off. I guess it’s part of me.

If there’s one thing that I really appreciate of the American culture is this idea that you can reinvent yourself and that maybe you should. That failure isn’t a bad thing. The important thing is when you show your strength and how you recover from that. That is a big contrast with what I was telling you about Chile and how I’m still labeled as a journalist. “Yeah sure, but not really.” I chose a different path than the one I did when I was eighteen going into college knowing really nothing. I think it feels good to be able to have flexibility. As an artist I think also it’s good to have that flexibility because you see so many artists sometimes trapped in a successful formula. Many times that is also a demand from their galleries and the market. I assume that if you become like a super big artist, you have all this pressure to continue being that successful. I think it’s great to have the freedom to explore within your own artwork and within your own practice and not be stuck with something.

I just learned how to knit, so who knows? Maybe my next work will be like a knitting piece. I don’t think so, I don’t think I’m going to get that good, but I think it’s good to have that opportunity. In general, I’m more drawn to artists that are versatile and ductil; you can see that in their work.

Groana

You mentioned being really interested in documentary. Do you see your practice being documentary in a way?

Andrea

No, but I can see the relationship. I don’t deny being a journalist. I think that what I went through really informs my work. I choose to work with materials that come from real life of real people. I work with other people’s memories, so I have this interest in nonfiction as a starting point, but then what I do with that is not necessarily what you would expect from a documentary film.

This allows me to question methods of representation and social discourse and a lot of things we are taught to believe and pursue. I’m not saying that documentary films can’t do that. Some of the French filmmakers of the New Wave era did it beautifully, like Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Agnès Varda. Or the Dadaists like Buñuel from Spain. I think that was a super interesting time of questioning the value of the image and storytelling. The challenges now have gone a little bit further than back then, but I like to go back to the roots because I really like their work.

Martha

I haven’t made that connection between your journalist background and Future Past News, which is like journalism but in a very different way. [Future Past News is a Virtual Reality installation that juxtaposes a 1937 newsreel with today´s news]

Andrea

That’s the most journalistic piece that I’ve done. I was editing the present news and writing all these texts to scroll down the screen. I took it very seriously and I think that’s probably because of my foundations. I also wanted to be very accurate with what we were showing.

I think it’s pretty far from what a lot of journalists practice today. I don’t know how many media professionals are questioning what they hear from different political or social actors or putting things in context. Either they have an idea of fake objectivity they want to pursue and they lack context, or they have a very biased point of view but aren’t honest about it.

I don’t think I was thinking about that either. It was just like it was so much in my face. I had this newsreel from 1937, with all these things happening and they’re all these things happening now. It just felt so similar… And when I talked to Karolina Ziulkoski about it, we were both like, “yes, it’s crazy, we need to do something with it” I think it was more like giving context to something. It’s really crazy because we’ve received some very hateful comments on social media from Trump supporters. They’re really good at trolling.

Martha

I guess it never crosses your mind when you put up a work like that.

Andrea

I had a sense it was controversial, but because it’s art I thought it would be viewed by an audience that had similar thinking and beliefs. But then it’s online and it’s out there and it’s on social media and anyone can see it. If I had to choose again the main image to promote it, I would probably pick something different—we have one that shows Hitler in the old newsreel and Trump on the phone.

Of course, I’m not saying Trump equals Hitler. In context, I’m saying the situations are very similar. I think that what he does is very similar to the way dictators and populist fascism work. I think that in choosing that image we narrowed the conversation. It was very easy for people to be binary about it.

Martha

And people can choose not to see the full conversation. Some people just read headlines and assume that the note is about something.

Andrea

What’s even more dangerous and worrisome nowadays is that a lot of people get their news from Facebook. That means they are only looking at items that are tailored for them from outlets and people that share the same views. That narrows your worldview so much, and it kind of exalts the ideas you already have. I wish people read the headlines from different media. I can’t deal with Fox News, for example, but I still like to know what they’re saying because I think it’s important to be informed and to get different points of views.