Amanda Gutiérrez, flâneuse redefined

Walking is rarely an end in itself. It is a way to get from one place to another. In a city like New York, it is a way to get from one meeting to another, or from one espresso to the next. To walk in New York City is, above all, to walk in a hurry. The Belgian-Mexican artist Francis Alÿs once said the following regarding his “artistic walks” throughout Mexico City’s downtown. “Walking, in particular drifting, or strolling, is already –with the speed culture of our time– a kind of resistance.”

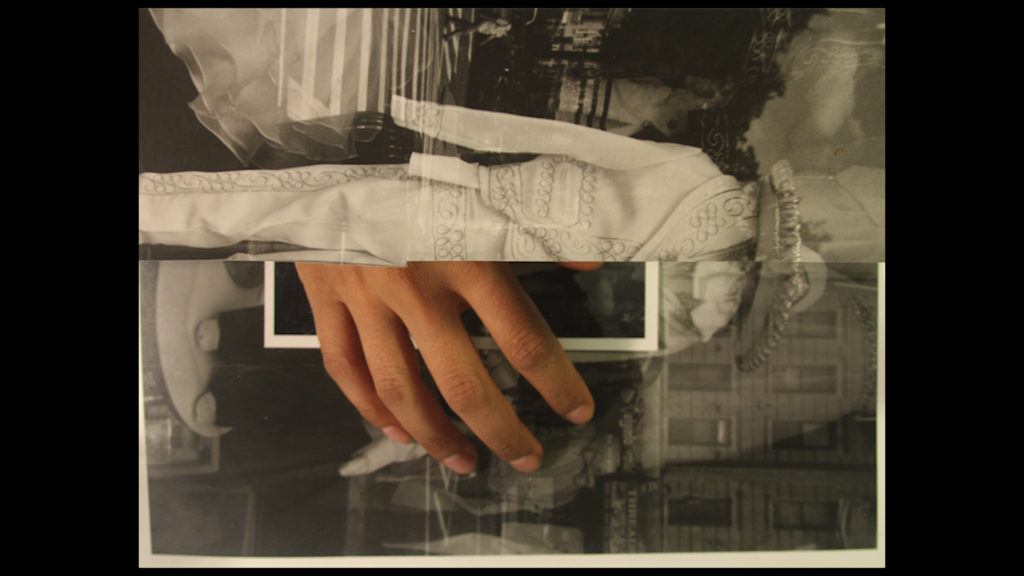

Mexican artist and activist Amanda Gutiérrez left Mexico in 2002 to pursue an MFA program at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where she began investigating the public space–mainly, specific neighborhoods–through walking. Over the past two years, she has continued her artistic practice in the streets of New York City, where she currently resides. Her exhibition, Walking in Lightness at Baxter St – a series of collages, photographic prints and a video– announces, even from its title, that walking is a central element, if not the central element, of the show. The works in the exhibition are all explorations of one of the most eclectic neighborhoods in Brooklyn, Sunset Park, where the predominant presence of Mexican immigrants makes her feel at home. The pumpkin flowers, fruit stands, mariachi clothes, huitlacoches and aguas frescas, which are sold along the barrio’s main street add to this sense of familiarity. In the video that has the same title as the exhibition, we see the hands of the artist manipulating a series of prints in the dark room while we listen to her narration:

I’m walking on a street that seems

familiar to me even when I have

never been here.

That is where other people with

cultural similarities concentrate,

revolt…

Eat and share things that are mute,

invisible to others.

Amanda Gutiérrez could be understood as subversive, strolling through the city at her own pace and opposing the convulsive rhythm of capitalism that sustains a metropolis like New York. But to begin to analyze the work of Gutiérrez, one should not only think of the walk as a criticism of the vertiginous rhythm of modernity à la Alÿs, but also, and above all, as an exercise of a human right.

The history of walking should ideally be, as Rebecca Solnit points out in Wanderlust: A History of Walking (2000), “a history of freedom and of the definition of pleasure.” However, the possibility of walking like this, freely and pleasantly, is determined by aspects of gender, race and class. It is the social and political conditions of the different regions around the world that determine who can enjoy the pleasure of walking and who cannot. Let’s think, for example, of Mrs. Dalloway-–the protagonist in Virginia Woolf’s famous book of the same title– who starts her day, one morning in June, by going out of her house to get some flowers. 1 While women (we must add, white upper-class women) could dare to wander and feel the bursting atmosphere of London in the twenties, today (almost a century later) a woman in Mexico, Honduras or El Salvador would put herself in position of vulnerability by doing so. Put in, say, Ciudad Juárez, Clarissa Dalloway would go get the flowers with fear. After sunset and in certain areas, she would perhaps not leave the house by herself at all.

Let’s pause to reflect on the following: in Mexico, more than seven women are killed each day. Moreover, in the last ten years more than 23,800 women have been killed: one of the highest femicide rates in the world2. In Mexico City, where Amanda Gutiérrez was born, walking alone through the city, like a flâneur 3 –or rather, a flâneuse– would not be free of risk. In her video piece, we hear Gutiérrez talk about the violence that women have suffered in Mexico during the past decades, violence which has moved her to live abroad and exercise certain rights more freely, such as that of walking alone:

“Why did I come here?

The safeness that I can’t find in

my own space.

The opportunities to keep walking

over my own shoulders.

(…)

I cannot describe the feeling of

seeing women with less luck

disappearing.

That’s why we are moving here

At least that is why I moved here.

Where there is some noise on the

sidewalks.”

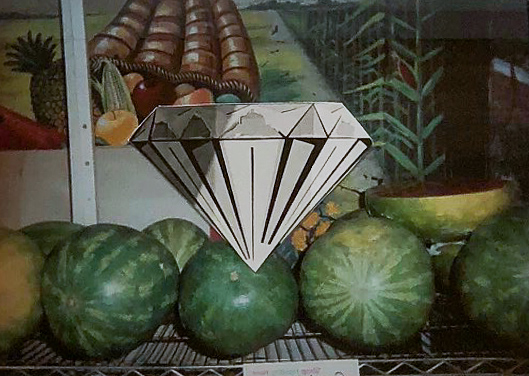

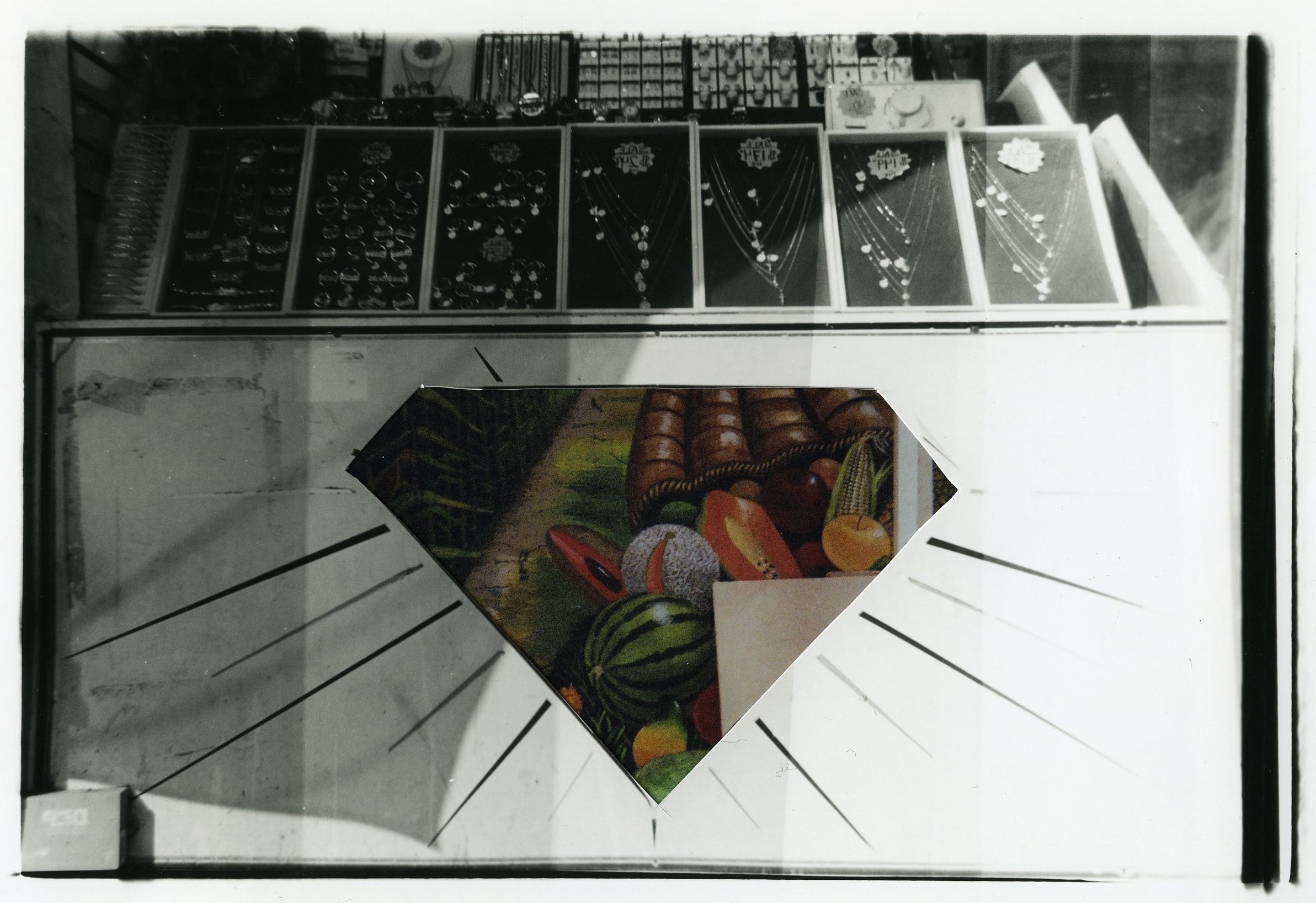

It often happens that neighborhoods populated mostly by immigrants are constantly constructed by adapting original rituals and iconic symbols from the cultures left behind. Be it Sunset Park, Harlem, or Chinatown, they all become a representation of a “paradise lost.” In the diptych Paradise Memories 1,2, (2017), Gutiérrez explores this idea by photographing the oldest Latin-American grocery store in Harlem, which has a mural of a rural dream-like scenario: fertile corn fields and harvests of tropical fruits. In an interview, Gutiérrez mentions that what attracts her to this mural is how these romanticized depictions function as a “placemaking” of neighborhoods, capitalizing on the sense of identity for the community.

Within that same line is the colorful series of photographs Calibrando Exotificación (2018), composed by nineteen C-prints of one single image in which we see four pineapples and a bunch of bananas hanging. This image could well be a photograph of any fruit stand in any Mexican market and is reminiscent of those spontaneous sculptures that Gabriel Orozco photographed in the 1990s –- images with infinite metaphorical possibilities. Here the pineapples and the bananas are barely leaning one against the other, almost affectively and somewhat vulnerably, like relatives who suddenly looked up to pose for a family portrait.

The nineteen C-prints that integrate this series are Gutiérrez’s experiments in the color darkroom: different time exposures deliver prints that are so dark, or so luminous, that the image is barely perceived; different contrasts and color intensities produce prints that are so excessively cold or warm that the image gets lost behind the prominence of color. However, rather than reducing this series to a mere formal investigation of light, color and contrast, one ought to ask: what is the calibration of color and lighting needed to reach the “right” degree of exoticism? What is the proper combination of exoticism and universality that international artistic products require to be validated by American institutions? How “Mexican” does the art produced by Mexican artists needs to be? What does it mean to be a female Mexican artist today in the global art world?

If Sunset Park provides Gutiérrez a spectacle of pineapples, bananas and papayas — a choreography of aesthetic codes that every Latin-American immigrant understands and extols — she seeks to find some tension in it. Her work hopes to dismantle any sort of national cliché. Although her work in Sunset Park starts with an appetite similar to that of an ethnographic researcher, one who tries to shed light on the codifications of the color, fauna and flora of the neighborhood, it does not acquire that flat nature of purely documentary photography. In her work, Gutiérrez does not present Sunset Park through a lens of nostalgia, but rather highlights how porous and malleable the different cultural identities are when they exist in and adapt to new geographies. In her explorations along Sunset Park’s 5th Ave, the combination of more than one nationality unfolds and suggests a plural temporality. Gutiérrez says, “Where today live Mexicans, Syrians, Lebanese and Asians, before that were Puerto Ricans and Dominicans and, tomorrow, who knows.” It is part of Brooklyn’s essence that diverse cultural practices intersect and impact one another. One of Gutiérrez’s challenges is to document this coexistence (which is not always harmonious) with just one disposable camera and without portraying a single person. In her work she has decided to never portray people, much less immigrants, “because of the state of vulnerability in which these people live already.” The result of this restriction is that the images become a bit more difficult to codify, demanding that the viewer renounce a passive stance and become an active participant in the understanding of the work.

In her series of collages, contrasting cultural and aesthetic symbols overlap and cohabitate the same frame. In Paradise Memories 3 (2017), a photograph that depicts four glass barrels filled with tropical aguas frescas juxtaposes another photograph of plants growing wildly in, the artist tells me, a vacant lot located just in front. In Similacrum 1 (2017), Gutiérrez shows us the outside of a laundromat maily frequented by women from the Middle East (we do not see the women in the image, of course). A notice with the slogan “If you suspect terrorism, call the NYPD” is attached to the laundry’s glass window. Below this black and white image is a fragment of a color photograph showing a piece of the yellow roof of the building located directly in front of the laundry (the building is a McDonalds, but we don’t see that either). This single frame contains the harassment experienced by Middle Eastern immigrants along with its counterpart: the popular bright-yellow symbol of the “American dream”. In both of these collages as well as virtually all of the pieces that compose Walking in Lightness, what may at first glance seem to be mere aesthetic explorations of transcultural dynamics, at second glance are, ultimately, pieces loaded with political meaning.

I will conclude by going back to the very beginning of the show and talk about the series of black-and-white photographs the viewer sees when entering Baxter St. The titles of these series are key. The first of them, Asimilación cultural o de cómo aprendí a ser ligeramente blanca 1, translates to Cultural assimilation or how I learned to be slightly white, and consists of four monochromatic prints of the same image, each one of them printed with different gradations of light. The image shows a trio of girl-sized mannequins wearing first communion dresses behind a store’s glass window. In the first print, the image is totally “burned” or underexposed, that is, it is almost a black print, and the mannequins are not even visible. In the second print, the image appears, but with just enough light to barely see some girl-like figures. In the third image, these “girls” become a little clearer, and by the fourth print these “girls” are completely whitened.

For a Mexican viewer like myself, these series of images ranging from black to white immediately refer to the terrible racist structure experienced within Mexican society. Racism in Mexico is perpetrated daily and, for many, sometimes invisibly. The logic of white supremacy that arose with the arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century and the consequent marginalization of indigenous people, has dragged through to the present in a very profound way. This is in part due to the overwhelming publicity of whiteness as the representation of success and power in the culture of global consumption. 4 As explained here by sociologist Mónica Moreno Figueroa, the idea that ultimately all Mexicans are children of both indigenous people and Spaniards, that is, the myth of mestizaje, is what serves to hide our deep racism. Our reality is that there is a hierarchy of skin color, and consequent practices of oppression against the dark skinned (morenos), the indigenous, and the Afro-Mexican are practiced every day in many ways. Racist practices are even perpetrated in intimate family dynamics.5 Federico Navarrete in his Alfabeto del racismo mexicano (Malpaso, 2017), sums it up in this way:

“In our social life we Mexicans place ourselves continuously, and are placed by others, on a chromatic scale that associates whiteness, natural or artificial, with beauty and privilege, power and wealth, and its “opposite”, that is, dark skin, with ugliness, marginality and poverty. This pyramid of phenotypes (…) allows us to determine, almost automatically, who deserves our admiration and envy and who our contempt and our pity.” (Navarrete).

The racial discrimination against the Mexican brown population only increases when crossing the United States border. In Asimilación cultural o de cómo aprendí a ser visible (2018), which translates to Cultural assimilation or how I learned to become visible, a triptych that follows the same formal exercise of applying different light gradations to one same image (the image of two boy-sized mannequins wearing the typical formal Mexican “charro” gowns), Gutiérrez reminds us how when brown Mexicans migrate to the United States, they are drained of any cultural heritage just to be rendered “illegals”. Their migratory status and the constant threat of getting deported relegate them to labors that accentuate their social invisibility, such as cleaning dishes behind kitchens. The discourse of white supremacy and xenophobia that has resurfaced so strongly in the United States during the last years has become an inescapable subject-matter for Gutiérrez. One of the many great achievements of these last series of photographs, and perhaps of Gutiérrez’ entire show, is that with the use of very simple imagery, she manages to bring light to an array of resistances. The imagery obtained from her repeated walks in just one neighborhood in Brooklyn highlights the many daily encounters which are invisible to most city-walkers, who rarely, if ever, notice the politics of their immediate surroundings.

—Lorena Marrón

Endnotes

1. The book opens with this phrase: “Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.” A few paragraphs later, Woolf beautifully addresses the atmospheric experience of Mrs. Dalloway walking in London: “In people’s eyes, in the swing, tramp, and trudge; in the bellow and the uproar; the carriages, motor cars, omnibuses, vans, sandwich men shuffling and swinging; brass bands; barrel organs; in the triumph and the jingle and the strange high singing of some aeroplane overhead was what she loved; life; London; this moment of June.”

2. (CEPAC)

3. Walter Benjamin described the flâneur as the essential (obviously male) figure of modernity, a sort of urban spectator/detective of the city in the XIX century.

4. Navarrete, Federico, Alfabeto del racismo mexicano (México: Malpaso, 2017), 19.

5. Moreno reminds us of the well-known dynamic that, when only a few minutes after the birth of a baby, family members ask if the baby came out dark or white (“güerito”).