Photography and Violence 2: Sontag vs. Butler

What does it mean to protest suffering, as distinct from acknowledging it?

Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others.

In last week’s entry, I inaugurated my participation in this blog with a quote by Jay Prosser, from his book Picturing Atrocity (2012):“Atrocity is going on all around us —he said— the least we can do is acknowledge it.” In the third chapter of her book Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), Susan Sontag explains how we have acknowledged suffering since the Christian depictions of hell or representations of famous biblical decapitations (like that of John the Baptist). But when did we start to use the iconography of horror to express our disagreement? Sontag recalls Jacques Callot’s (1592–1635) eighteen etchings titled Les Misères et les Malheurs de la Guerre (The Miseries and Misfortunes of War) from 1633, which depicted many atrocities committed against civilians by French troops during the invasion of his native Lorraine in the early 1630s.

In his etching No. 5, “Plundering of a Farm,” Callot uses both image and text to describe a scene in which soldiers murder, kidnap, steal and rape.

Here are the fine exploits of these inhuman hearts

They ravage all over, nothing escapes their hands

One invents forms of torture to get some gold,

The other, having committed 1,000 crimes, encourages his accomplices

And all in accord, they maliciously commit

Theft, kidnapping, murder, and rape.

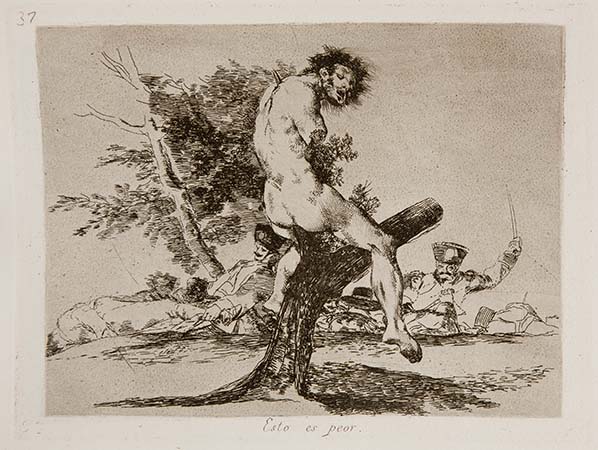

Between 1810 and 1820 Goya created Los desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War), a series of works that could be seen as a “visual protest” against violence, specifically the atrocities perpetrated during the occupation of Madrid by French troops during the Peninsular War (1807–1814). He used various sketches to narrate violent scenes, such as the depiction of a disfigured body found mounted on a tree, and also included a brief caption which, rather than serving as a description of the event, functions as an expression of dissent by the artist: “This is worse” wrote Goya below one of these pieces.

Is Goya’s “protest” implicit in the image, or is the caption the element that “protests”?

At first it’s easy to agree with Susan Sontag that, when it comes to photographs, the image cannot offer itself an interpretation; that protest requires a caption in addition to an image to have any sort of political meaning. But we can also take another second and contest this view. Judith Butler, in her book Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (2010), explains that framing already presupposes decisions and practices that leave substantial losses outside the frame. Inclusion and exclusion already affect the political meaning of an image. Despite the fact that Butler agrees with Sontag that we need captions and analysis, the frame, she argues, is never neutral. The image has already determined what will count, whose life will be grieved, what is perceivable and what isn’t.