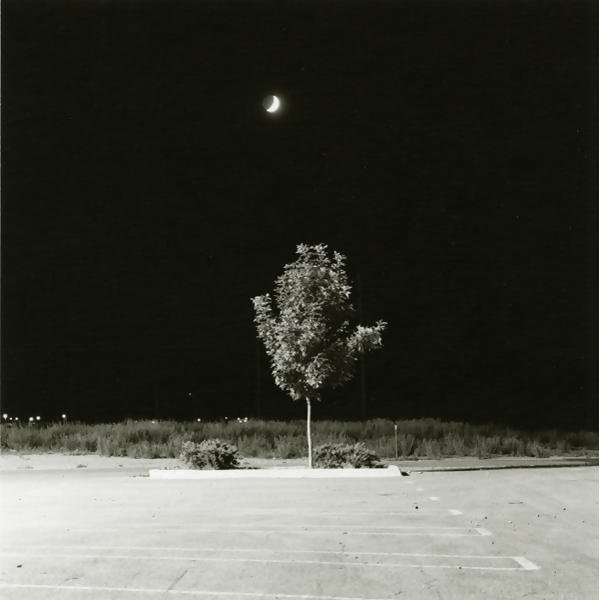

The moon was the first photograph

There’s a Lucinda Williams song that she often opens shows with called “Pineola,” concerning the immediate aftermath of the suicide of the poet Frank Stanford in 1978. He was most well known for the massive, unhinged epic poem The Battlefield Where the Moon Says I Love You. At his funeral, his Pentecostal family was shocked to see so many people in attendance; they had no idea that he was widely well-regarded – or even regarded at all – as a writer. Anyway, I bought What About This: Collected Poems of Frank Stanford sight unseen just after it came out this year.

It became clear pretty quickly that if you did a word cloud on these collected poems, “moon” would be pretty high up there, like in definite article territory. I wasn’t the only one who noticed this, apparently; the Readings section of Harper’s soon ran “Lunar Phrases,” a little collection of references to the moon in Stanford’s verse. Here it is:

And the moon /?Was a dead man floating down the river

the moon?/ was the blind eye of a fish?/ in the back of a cave

the moon was a salt lick?/ for her cattle of darkness

the moon?/ It is a piece of butcher’s ice

the moon full and flowing this side of Ozark / Smoldering like a burnt tick

Night and her moon?/ Like a widow with child

the moon like a bleeding toenail?/ the dancers will pass by

moon hung together with dark?/ like camp dogs in a ditch

The moon was swollen up?/ Like a mosquito’s belly.

the moon.?/ It was a clock with twelve numbers

the moon?/ Was a piece of stationery?/ In a drawer she would not open.

The moon is your old shirt.

And the moon was his white piano

And the moon was a body.?/ I don’t know who put coins over her eyes.

the moon?/ Flinching behind the trees.?/ It was a white flower?/ Afraid to be cut down from its dark stalk.

the moon, the old cow?/ That chewed its way out?/ Of the darkness in our fields.

the moon.?/ It was like the light blue handkerchief?/ She gave him to go with his dark suit

the moon wades a creek?/ Like an albino with a blade?/ Fixed to a stick.

Now the moon was a fifty-cent piece?/ It was a belly I wanted to cut open

the moon in the woods flashing?/ Like a girl running in her panties.

The moon went back into its night?/ Like a blue channel cat in a log.

I liked these excerpted in this way not only because the metaphors are so good, but also because they are for the most part concrete. Like you could make pictures based on them. Like you could put a bunch of those pictures together and make a book of them: the block of ice, the bleeding toenail, your old shirt, an old cow. And they would all be the moon.

And they would be sad.

Mary Ruefle in “Poetry and the Moon”: There is a greater contrast between the moon and the night sky than there is between the sun and the daytime sky. And this contrast is more conducive to sorrow, which always separates or isolates itself, than it is to happiness, which always joins or blends.

That’s another quality of Stanford’s metaphors: isolation. Also a quality of photographs.

Ruefle says later: [T]he moon was the first poem, in the lyric sense, an entity complete in itself, recognizable at a glance, one that played upon the emotions so strongly that the context of time and place hardly seemed to matter. “Its power lies precisely in its remaining always on the verge of being ‘read,’” says [Charles] Simic, speaking of photography, and I see the moon as the incunabulum of photography, as the first photograph, the first stilled moment, the first study in contrasts.

I had to look up “incunabulum.” Wikipedia: “incunabula,” Latin for ‘swaddling clothes” or “cradle,” which can refer to “the earliest stages or first traces in the development of anything.”

The moon is the cradle of photography.