Day in Ellis Island, 1951: Erika Stone Portfolio

Erika Stone doesn’t remember the exact day but in 1951 the adventurous photographer spent a day at Ellis Island. A German immigrant whose father was held at Ellis Island briefly, before he moved the family to New York in 1936, Stone didn’t photograph Ellis Island with the gaze of a passerby, but with the awareness of a passer-through. This previously unpublished portfolio of Ellis Island photographs shows a glimpse of how Ellis Island functioned before its closing in 1954. On its first day of operation 700 immigrants passed through Ellis Island in 1892. Before the first immigration station opened in 1855, at what is now Castle Clinton, immigrants arrived directly at Manhattan’s various harbors and entered without being monitored.

Discovering how people lived, survived and thrived in urban conditions was Stone’s primary photographic direction. In the vast archives of Stone’s work we find sophisticated street photography compositions, casual glances of lovers in the park, exuberant neighborhood personalities, and the playfulness of children. A street photographer making frequent trips to the ethnically diverse neighborhoods of New York City’s boroughs, Stone photographed people from various walks of life, unimpeded by racial and economic divides marking the times and places in which Stone worked. Born in 1924, Stone studied photography at the New School of Social Research with Berenice Abbott and George Tice. A member of the New York Photo League and a stringer for Time and Der Spiegel in the 1940s, Stone made hundreds of photographs before, during, and after raising two boys in New York City.

Home to the world’s largest immigrant population, the US counts 41 million New Americans among its population. As conservative political conversations point to strategies for thickening walls of separation, a recent Pew study shows that US population is more accepting of New Americans, although it’s really by a small percentage. During its first year nearly 450,000 immigrants passed through Ellis Island, while this year alone 300,000 migrants and refugees have arrived in Greece, trying to reach other EU countries.

As we live through the world’s largest refugee crisis on record, will European Union countries ever view migrants as “New Europeans”? Are the processes of immigration reform in the US transferrable to the EU? Are the motivations for building Hungary’s razor wire fence really so different from “The Great Wall of Mexico”? I’m using the term migrant in reference to displaced people with uncompleted legal processes of claiming asylum, fleeing war-torn countries, and economic migrants. I pose this question because the value we place on migrant and refugee lives changes how we talk about them, how we choose images to portray this urgent humanitarian condition. David Cameron, Britain’s prime minister, asserted that Britain was doing “enough” for migrants and refugees, but quickly moderated his position after being “deeply moved” by seeing photographs of Aylan Kurdi. To look at photographs of people in crisis without establishing a social value for such lives is a grave mistake.

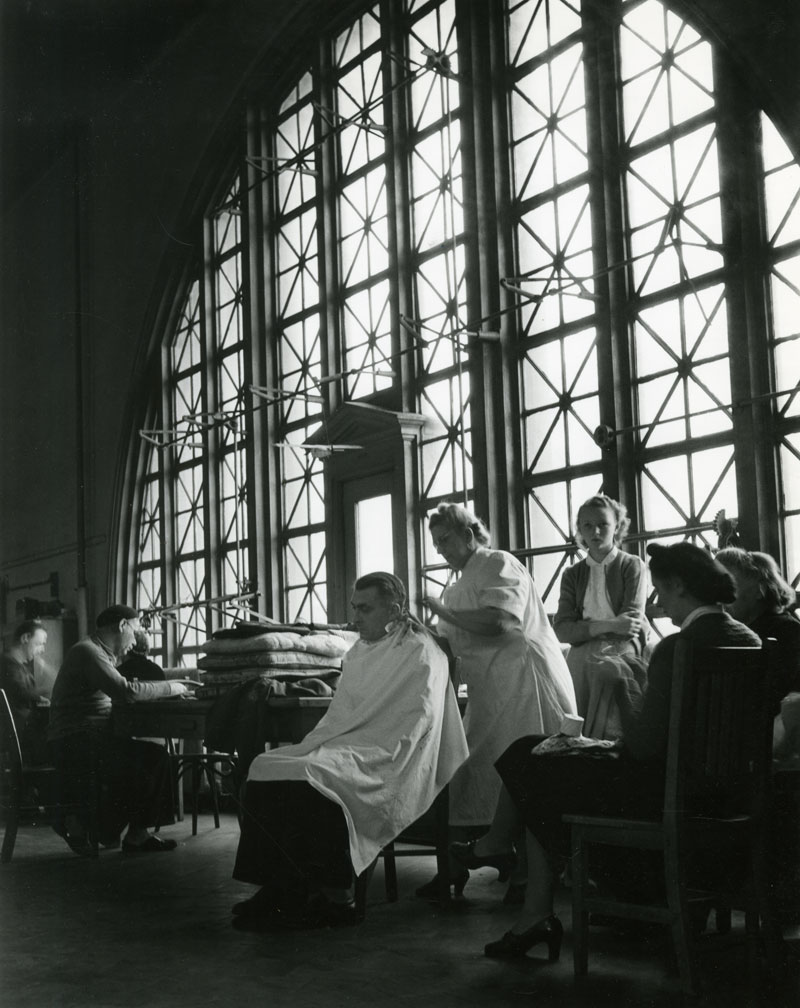

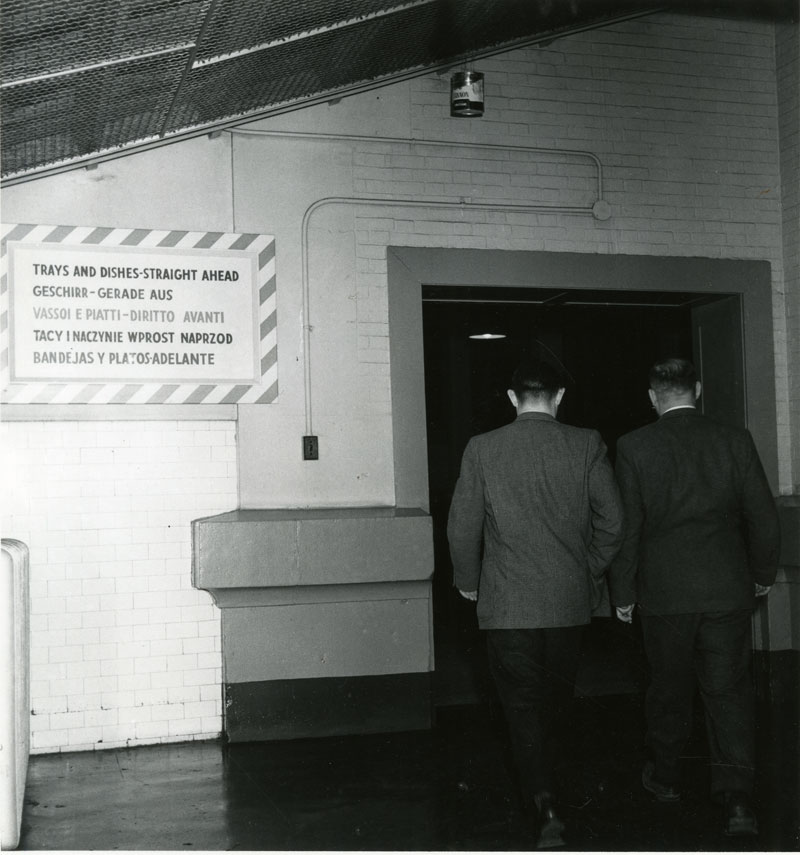

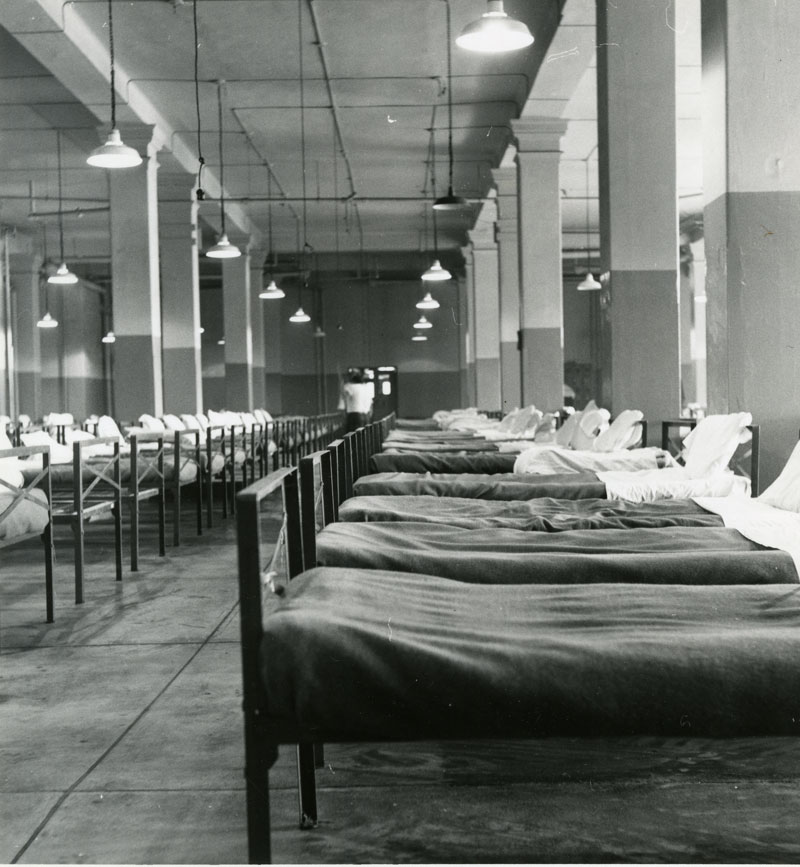

The Nov. 13, 1950 issue of LIFE featured an editorial on Ellis Island with photographs by Alfred Eisenstaedt and a text describing the Island as a “…gray and gloomy place suddenly full of bewildered people who have become victims of American politics.” Stone’s focus on the Island was not limited to the concerned photography ethos of the ‘40s and ‘50s New York: Stone takes us through the daily rituals of living in limbo: sleeping, eating, socializing, grooming. What we see in Stone’s photographs of Ellis Island is very a different view from Eisenstadt’s in 1950, and from Lewis Hine’s longer series. Both Eisenstaedt and Hine focused on people and their physical markers of displacement, while Stone captured unexpected daily contexts, such as two men walking to the dining hall, a flood of light illuminating the back of a neck close to the blade.

When Erika Stone made these photographs in 1951, one million people had yet to find settlement, due to the migrant crisis of WWII, according to a UN report. Revisiting Stone’s photographs in comparison to today’s images of immigration control and containment brings us closer to the larger history of photography centered around the human experience of crossing borders in order to live.

Day in Ellis Island, 1951

An unpublished portfolio of photographs by Erika Stone

Erika Stone, The Barber, 1951. Photograph courtesy of Erika Stone.

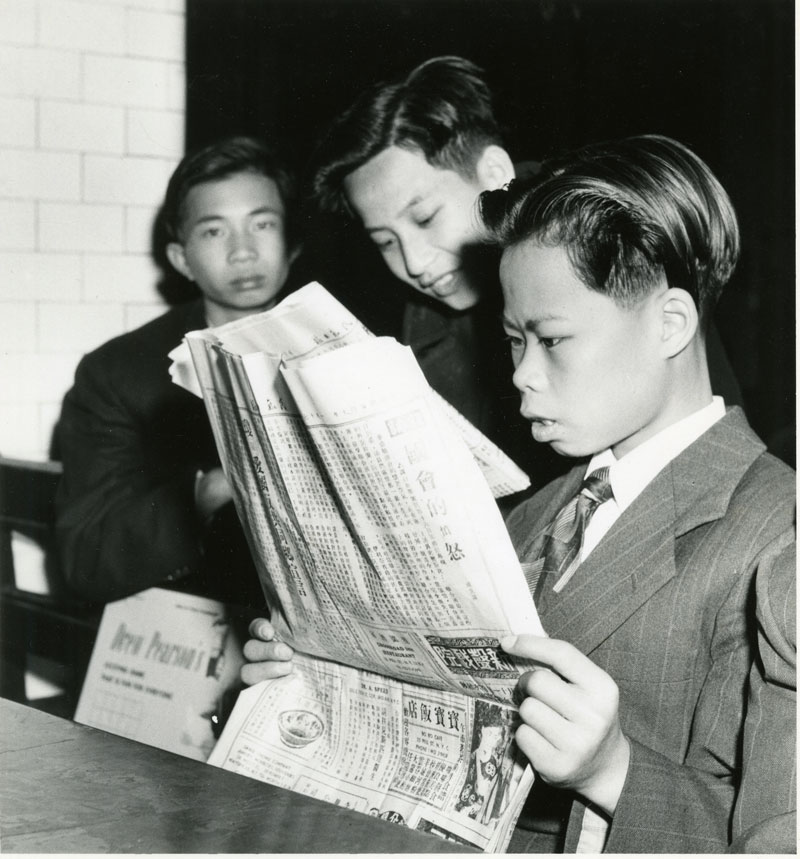

Erika Stone, Boys Reading, 1951. Photograph courtesy of Erika Stone.

Erika Stone, The Dining Hall, 1951. Photograph courtesy of Erika Stone.

Erika Stone, The Dining Hall, 1951. Photograph courtesy of Erika Stone.

Erika Stone, Entrance to the Dining Hall, 1951. Photograph courtesy of Erika Stone.

Erika Stone, A Family Room, 1951. Photograph courtesy of Erika Stone.

Erika Stone, Arriving at Ellis Island, 1951. Photograph courtesy of Erika Stone.

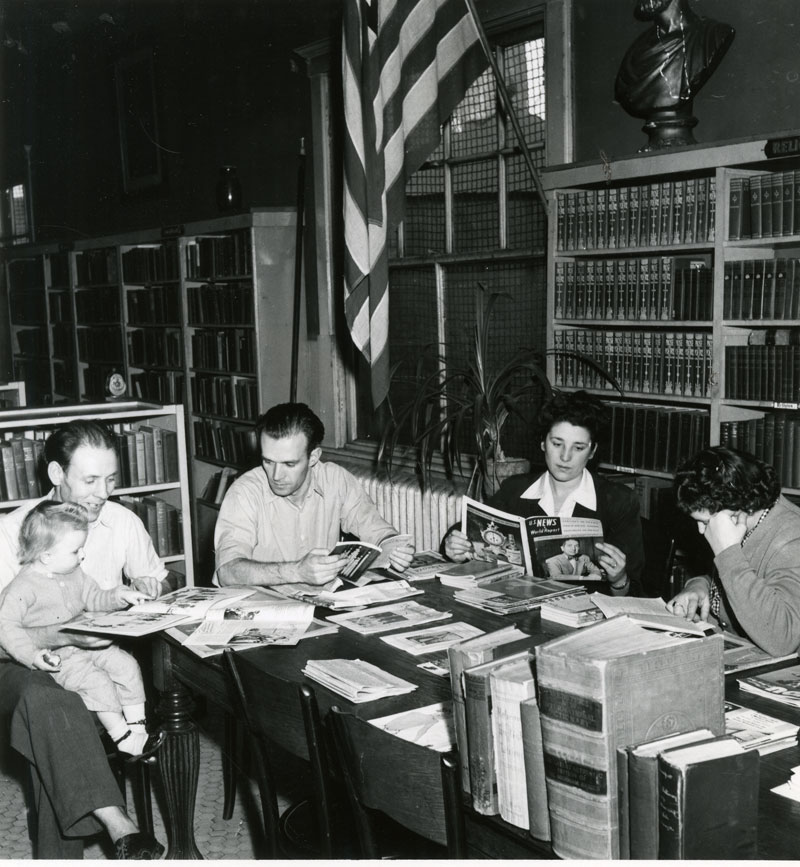

Erika Stone, The Library, 1951. Photograph courtesy of Erika Stone.

Erika Stone, Single Beds, 1951. Photograph courtesy of Erika Stone.

Erika Stone, Luggage, 1951. Photograph courtesy of Erika Stone.