Elliott Jerome Brown Jr. and the Paradoxes of Representation

Author Ralph Ellison prefaces his 1952 novel “Invisible Man” with a matter-of-fact explanation for the narrator’s invisibility: “I am an invisible man,” the story begins. Not in a literal way, as the Invisible Man from H.G. Wells’s 1897 sci-fi novella, or not due to a “bio-chemical accident to my epidermis,” either. His invisibility occurs, he writes, “simply because people refuse to see me.” As a young black man coming of age in early-twentieth century America, Ellison’s narrator – whose name is never disclosed – struggles to find his true identity living in a society where his individuality goes unrecognized because of the color of his skin. “When [people] approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination – indeed, everything and anything except me.”

Although this milestone of American literature was released over 60 years ago, the importance of a conversation about black representation today feels more urgent and pertinent than ever. As the duality of “how people perceive you vs. how you portray yourself” goes back to the cultural forefront, some artists use their personal stories to drive the narrative.

In a simple song, the photographer Elliott Jerome Brown Jr. builds upon Ellison’s invisibility concept, adding intimacy and the domestic space to ignite a conversation about contemporary black representation, queerness, and identity.

Her caress, a proposition to meet the front of the mirror, or an offer of protection for where I am. She offers a timeline – if not now, then later. At noon I’m scheduled for body awareness training. After all, I only realized minutes ago that my handwriting dabbles in illegibility. I’m told I won’t sweat, but that I’ll feel big inside like I can breathe again., 2018

Brown drew inspiration for the show from Billy Preston’s 1971 album “I Wrote a Simple Song,” whose title song alludes to the perils of altering artistic expression to conform to an idea that’s expected from you. It describes a song that was originally conceived as a private conversation between songwriter and muse, but embellished for commercial use, and in the process, altering its true essence.

They took my simple song, yes, they did

They changed the words and the melody

Made it all sound wrong, yeah

Now it sounds like a symphony

Preston was a famed African-American musician who frequently collaborated with The Beatles and the Rolling Stones. He allegedly struggled to reconcile his homosexuality with his relationship to the church, and never came out publicly as a gay man; he was posthumously outed by Keith Richards in his 2010 autobiography “Life,” where he writes: “[Preston] was gay at a time when nobody could be openly gay, which added difficulties to his life.” The lyrics to “I Wrote a Simple Song” are directed towards a woman:

That song was personal

Because I wrote it for you

It’s yours and mine, girl.

Like the unnamed narrator in Ralph Ellison’s novel, whose attempts to define himself through the expectations imposed on him by others are rendered inauthentic, Preston talks about the compromise of artistic integrity in lieu of outside expectations with “I Wrote a Simple Song”.

The nine pieces Brown brought to a simple song speak to this tension between the public and the private, the intimate and the distant, the personal and the collective, the visible and the invisible. They portray intimate slices of black life – himself, family, friends – that contain elements which are often obstructed from the viewer. The faces in his photographs are rarely ever the focal point. The subjects are often distanced from the viewer: turned away from the camera, seen through a mirror reflection, or with their eyes closed. Some have their faces blocked by a visual element – either as part of the composition, or as an external sculptural artifice. There’s a palpable distance between sitter and viewer, and the narrative thread is left ambiguous on purpose.

He gave and he gave,/but he wouldn’t have given at all if I didn’t let him in,/if I didn’t cover my body in soap three times,/swish oil between my teeth 47 minutes ahead of the time,/that I expected him (Wounded), 2018

Brown has always been interested in “how intimate experiences are revealed as both personal artifacts and sociopolitical stimulus.” In one of his earlier works, “The Ramble (2012),” a series he completed during his freshman year at NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, he references a well-known gay cruising area in New York’s Central Park. Exploring and exposing such an intimate detail of the gay experience allowed him to open up and feel more comfortable about sharing his sexuality with the world. “I became more interested in how we make our private lives public and how much of ourselves is influenced by public histories.” As a gay black man, the idea of identity and representation takes center-stage in his work, a concept that has permeated his images from the start, but flourished after he started using his own body to express the intersection of queerness and blackness.

From The Ramble series, 2014

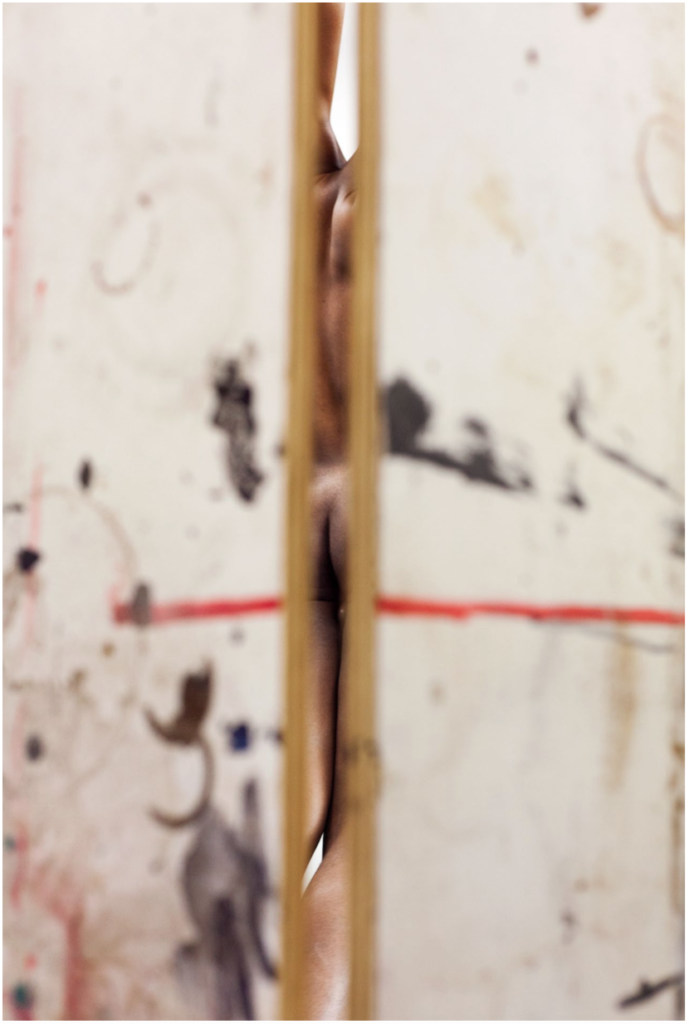

A self-portrait from those earlier days, “Pendulum (2014)” speaks to that dynamic. In the image, his nude body is seen through a sliver in what appears to be a wardrobe or a closet. He has his back to the viewer, and he’s dangling from the ceiling, holding on to an object. The object can’t be seen in the picture, but the tightness of his muscles – from his shoulders all the way to the bottom of his thighs – gives away the tension. The work is emblematic of how he likes to tell a story, and it became a recurrent theme is his images: the sitter looks away, so that the viewer can look in. “That image blew me away in that I can still discuss whatever it is I want to discuss at that time and not necessarily have people preoccupied by my identity, or the identity of the sitter,” he said.

Pendulum, 2014

While it’s a known part of history that black representation in the arts has been overlooked in this country, addressing representation in black photography by African-American photographers has been especially abysmal. The first issue of Aperture dedicated exclusively to the “photography of the black experience,” for example, came out just a few months before President Barack Obama left the White House. Entitled “Vision & Justice,” the issue was inspired by an 1864 speech by Frederick Douglass, “Pictures and Progress,” where the abolitionist hero spoke about the transformative power of photography. Still in the dawn of the new medium, Douglass could already envision the tremendous role that photography would play in shifting people’s perception, as he underlined the importance of representation. He was “intent on the use of this visual image to erase the astonishingly large storehouse of racist stereotypes that had been accumulated in the American archive of anti-black imagery,” the historian Henry Louis Gates explains in the issue.

Brown takes this concept further. The biographical information in his photography is not usually what drives the image. “I’m interested in the residue of presence or activity, which encourages a slower, more ambiguous reading, versus an image that explicitly shows that action,” he says. In a way Brown plays up a paradox of sorts; he represents by not representing.

Grandma & Grandpa through the mirror, 2015/2018

–Muri Assunção