Herve Guibert, Ghost Image

Herve Guibert’s L’Image fantome was published initially in 1982. The English translation, Ghost Image, by Robert Bononno, I have came out in 1996, from Sun & Moon Press, and is available currently from Green Integer Press. The book is comprised of short written pieces which were published originally in Le Monde. A posthumous volume, La Photo, inéluctablement, was published in 1999, which has not yet appeared in English.

Guibert, known primarily for his books, also photographed. Several years ago I saw an exhibition of his photos at the Cultural Services of the French Embassy, on upper Fifth Ave., just below the Met, & I have a book published by Schirmer/Mosel. From 1993! (It seems so not so long ago).

The pieces in Ghost Image are short, some the length of a paragraph. Although notable photographers are mentioned (Henri Cartier-Bresson, Diane Arbus, August Sander), the pieces discuss photography in the everyday: Family photos, identity photos, album covers, film stills, etc., as well as the acts of photographing, the tensions & disappointments of it. I enjoyed particularly an account of an adolescent infatuation with a still of Terence Stamp in the Fellini film Toby Dammit (in which Guibert mistakenly refers to the Stamp character as the devil, when in fact Stamp is more a Swinging London version of Faust, who has sold his soul). There is a diaristic aspect to the writing – family episodes are recounted, memory is intertwined with photography – and it is public and brief, in a form that is perhaps more familiar to blog readers of today. Truly, it seems prescient of so much web writing now, although with a much more delirious perversity and greater powers of observation:

. . . I recall an incident that made a great impression on me when I was 8 or 9 years old. My sister was 12 or 13 at the time, and her breasts were just beginning to develop; high and firm, we had already seen them at the beach the year before, but that was the last time, because the following year they were covered up by a bra. That morning, it must have been a Sunday, my sister was locked in the bathroom. My father was at the door, camera in hand, trying to get in. He said, without hiding his intention, that he wanted to photograph his daughter’s breasts, because at that age, the moment of their initial formation, they are at the height of their beauty, and if they weren’t photographed then, that state of perfection would be lost. That was the extent of his argument. At the time, he sadly renounced his failed attempt at appropriation through the image and fought against that limit; he wanted to push back by a notch the phase of abandonment, of renunciation and at the same time, extend his role as a father in order to assume that of a lover within the conventions of voyeurism, for between the father and the lover, desire was probably not very different. . . “Inventory of a Box of Photographs”

Photography, in Guibert’s book, is a multiplicity of effects. It is a technological reinforcement of morbid curiosities, it facilitates social controls, it supplants memories, dreams and perceptions, replacing them with its own mediated Olympus of illusions.In “Photographic Writing” Guibert finds photographic aspects in descriptive writings by Goethe and Kafka – looking backward from the perspective of the technological present to a pre-photography concealed in language. Without any direct quotations, I find traces of Walter Benjamin, Siegfried Kracauer and Roland Barthes in Guibert’s considerations of the social aspects of photography. Barthes makes an appearance as “R.B.” in “The Photograph, As Close to Death as Possible” which is an account of Guibert approaching R.B. to photograph him with his ailing mother, who in the interim, died. Guibert presents his own lust for photographing in equivocal terms: it is morbid, it is fetishistic, it is selfish. & the compulsion can be sweet as well.

Written with almost aphoristic brevity, these episodes of photography seem both exceedingly particular & also informed with much larger ideas. To continue with photographic metaphors, these vignettes are like snapshots, fragments which indicate a much larger whole. I last read the book in what must have been 1996-1997, when the translation was published. Rereading it has been as stimulating as I can recall it to have been, with what seems new finds:

A Japanese dancer from the Sankai Juku group dances with a peacock. His entire body is very white, powdered with white clay, and his head is shaved. He wears nothing but a plain linen loincloth tied around his waist and stands out in relief against a wooden backdrop to which varnished fishtails and enormous fins from some cetacean have been attached. He embraces the peacock like a woman in a swoon, and the pattern on the bird’s plumage extends his loincloth with a gold-flecked train. We can see that the peacock’s thighs and feet are very muscular, like an ostrich, but the dancer keeps them bent, broken at the joints, and immobilized in his left hand, pressed against his side. His right hand encircles the peacock’s neck, stretches it, plays with it as if it were a delicate instrument, squeezes it almost to the point of strangling it. Everything is limited to a few contractions, and to the flow of blood, which he must feel and control with his palm: the Japanese dances a kind of slow-motion tango with the peacock, he dances with the peacock’s fear, with its vital fear of death. It really is an extraordinary moment, one of great tension, great beauty. But when the dancer releases the terrified peacock, we no longer know where to look, and our eye, which wanders between the dancer and the bird, loses its orientation. The peacock is nothing but a big terrified fowl who scratches around stupidly and snares itself in the cord that restrains its feet. The dancer is nothing but a dancer gesturing slowly. Our fascination has worn off, and rather than be deceived, we prefer to divert our gaze to the empty space between them, where the magic was created, the site of a latent photograph. Morever, when the Sankai Juko group came to Paris, many people, many photographers, returned to the performance with their cameras mounted on tripods. They bought seats in the front row and waited for the appearance of the peacock. They fired away – they were guaranteed beauty. That eminently photographic image, however, doesn’t belong to them (what is it that eludes photography here, except the infintesimal movements of contraction of the peacock’s neck, which are essential to the dance?), it belongs to the dancer, and he has decided that this will be a dance and not a photograph. And we might reiterate that beauty, like theater, is tied to the ephemeral, and to loss, and can’t be captured. Only I would prefer that photographers put more dance (or theater, or cinema) into their pictures, just as the dancer had put photography into his dance. – “Dance”

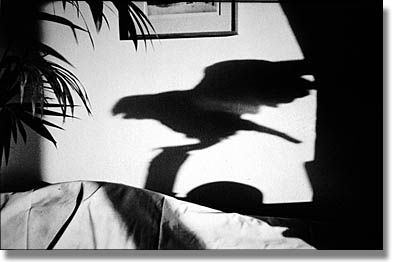

Herve Guibert, L'ombre de l'oiseau, 1982

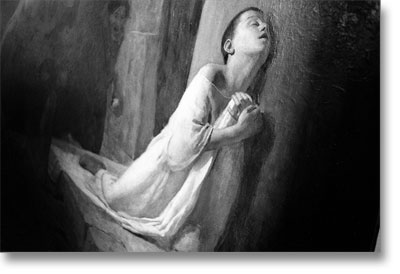

Herve Guibert, St. Tarcisius, 1990