Horror of Photography : Dillon DeWaters

Try, for a moment, to image what it would be like if you were the last person left alive on Earth. There are about a thousand reasons why such a thought is terrifying; you’re utterly alone, there’s no one to talk to. Even if you manage to survive on your own for years, the knowledge that the human race ends with you is always in the back of your thoughts. It’s not surprising, then, that literary and cinematic history is rife with works of fiction based upon this scenario. Part of what makes this notion so terrifying is the unknowable, post-human reality that persists (we can only assume) after we have all perished. This is an invisible future, shaped by forces that are outside the scope of human vision. For Dillon DeWaters, “making visible the unseen”, in his words, is one of his motivations as an artist, and he does it quite well.

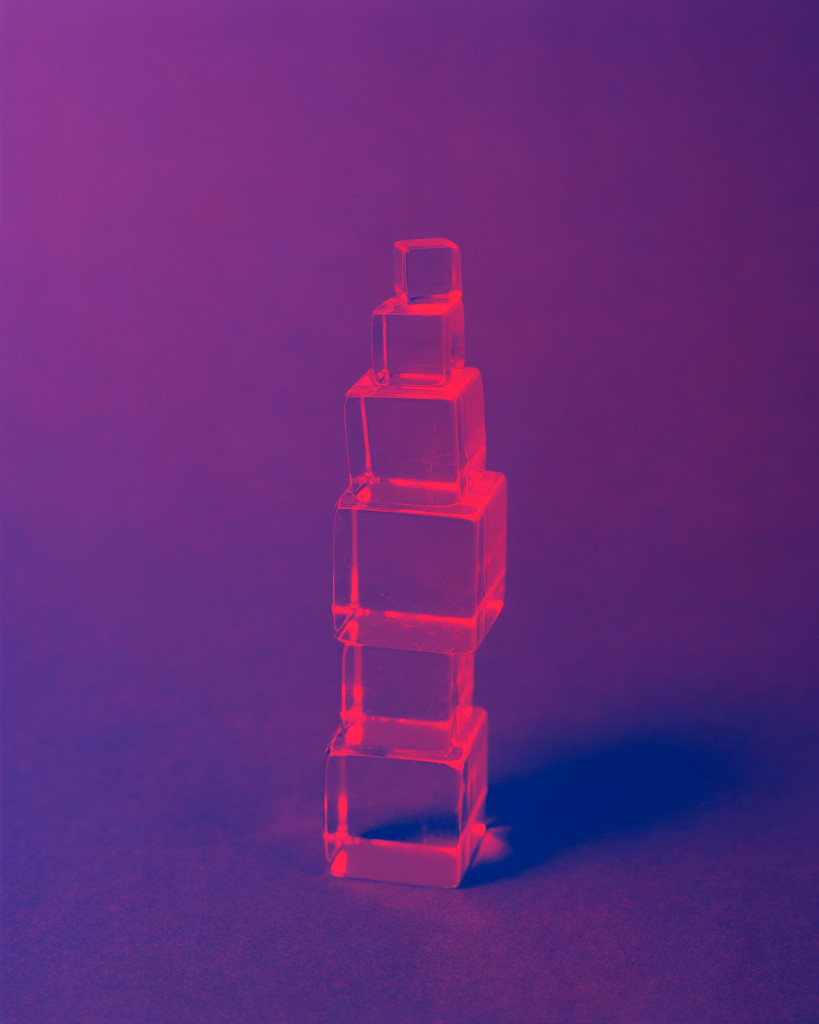

Dillon’s process is fairly straightforward in description: It largely consists of multiple-exposures with colored gels on medium-format film and minimal post-processing. He gets almost all of his effects in-camera at the time of exposure, not digitally. But, as is often the case, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Combining exposures in this way causes ripple effects from the first images to wash over and alter the way the second is rendered on the film. The result is typically a strange hallucination of both and neither image simultaneously. For Dillon, the unseen that he’s striving to make visible shows up where the two overlap. It’s no minor feat that Dillon achieves these seemingly effortless effects completely in-camera, given the unpredictable nature of his process. Dillons has found a way to divine a visual order from this invisible and unpredictable process.

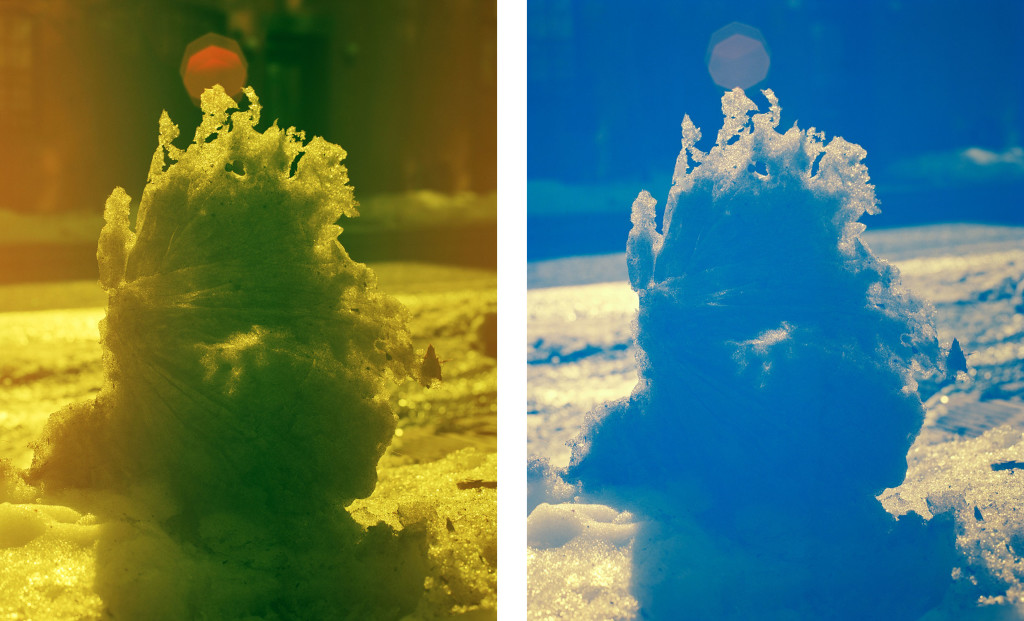

When I visited his studio, Dillon and I talked as much about reading as we did about photography. A voracious reader, Dillon names a wide range of literary influences, from Walt Whitman to the speculative fiction of H.P. Lovecraft. Nods to these influences show up in his titles. One of his current projects, Weapon, Shapely, Naked, Wan, takes it’s title from Whitman’s Poem Song of the Broad Axe. Whitman lived in and around Ft. Greene Brooklyn, and was a major advocate for the creation of the park that bears the neighborhood’s name. Many of Dillon’s recent images recount a photographic ghost-hunting expedition of sorts in Ft. Greene: his multi-exposure process revealing the underlying nature (no pun intended) of the park and it’s environs, taking the words of Whitman as a cue.

And despite recent infusions of figures in Dillon’s images, the human form appears more as a spectre or outline than a straightforward portrait. Slivers of light, faint outlines, and obscured features read to me like Dillon’s hallucinatory riffs on Sugimoto’s wax figures: they are filled with references to life but they aren’t exactly human either. In Dillon’s mind, these figures provide the context of narrative to the images; they give us as viewers a way of inhabiting this world Dillon is recording. The human figures in the work are less active participants in a storyline than they are uncertain detainees in that weird limbo between being and nothingness. Dillon told me that he’s striving to allow this nothingness to be a participant in his work; if that’s the case the deck seems fairly stacked against us.

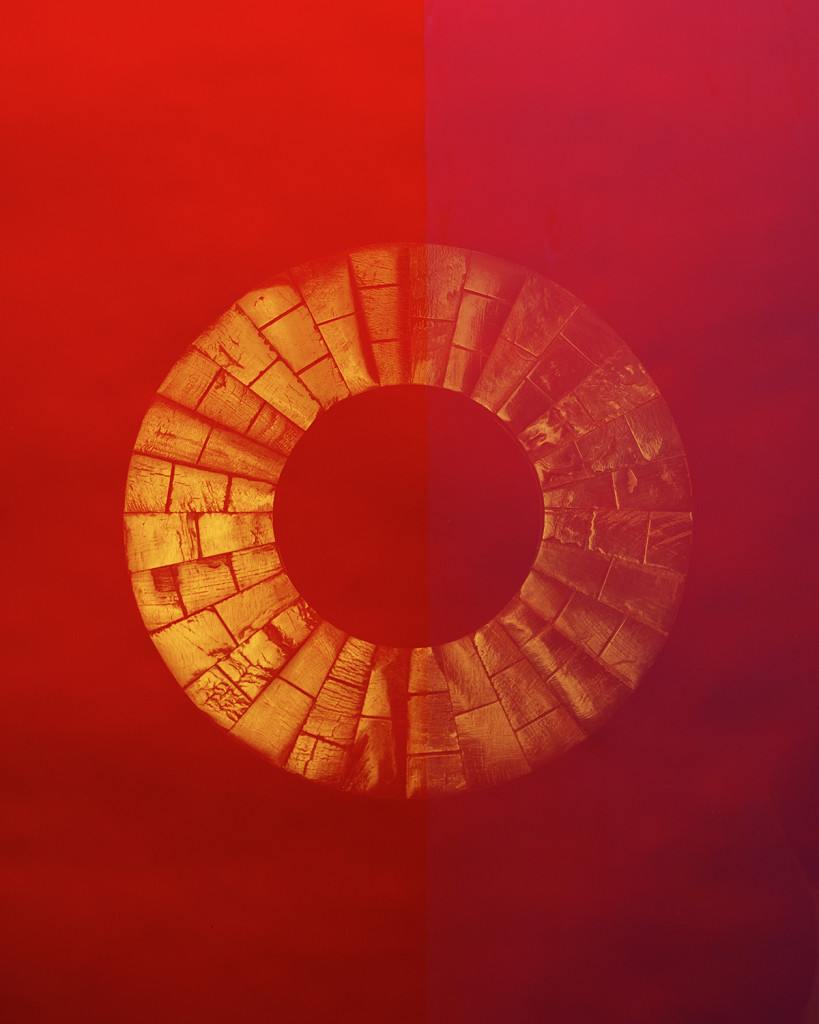

The title of this post, if you haven’t already guessed, is taken from Eugene Thacker’s book In the Dust of this Planet: Horror of Philosophy Vol. 1. In this first volume, Thacker takes the idea of nothingness, the unknowable, and what he describes as the-world-without-us as his starting point. “The-world-without-us”, he says, “is the subtraction of the human from the world” and lies “in a nebulous zone that is at once impersonal and horrific”. With requisite nods to the philosophical history of nihilism, Thacker proceeds to examine these ideas through the horror genre in literature, film and popular culture. In particular, speculative fiction, a big influence for Dillon, plays a leading role in the way human culture has attempted to grapple with the limits of human knowledge, and the fear of forces both natural and supernatural that lie outside the threshold of our senses. And in a lot of ways, this is exactly what Dillon is doing in his work. Rather than use words, (or as in the case of H.P. Lovecraft, an economy of words) Dillon uses an economy of visual forms and allows us to, paradoxically, gaze into this nothingness.

This oxymoronic “manifestation of nothingness” is explored in depth in Thacker’s book, and in particular, his chapter Six Lectio on Occult Philosophy. This section systematizes the ways in which the unknown, the supernatural, and the “weird” intersect with the human world; magic circles as in Faust, strange radio signals from deep space, incantations, seances, etc. Dark clouds, fog and mist are a common motif as well. Which brings us full circle to my question at the beginning of this post. Thacker says that “the mist in these types of stories is not only itself vaguely material and formless, but in many cases its origins and aims remain utterly unknown to the human beings that are its victims.” He names M.P. Scheil’s 1901 work The Purple Cloud as a “blueprint” for the mist motif in speculative fiction (he actually says that “In The Purple Cloud [..] it is through mist that the hiddenness of the world manifests itself “) The story is that of the last man on earth, told through his diary entries, after an ominous purple cloud descends upon civilization and wipes out everyone in it’s path. I’ll leave you two entries that seems eerily appropriate for Dillon’s work:

Alone that same day I began my way southward, and for five days made good progress. On the eighth day I noticed, stretched right across the south-eastern horizon, a region of purple vapour which luridly obscured the face of the sun: and day after day I saw it steadily brooding there. But what it could be I did not understand.

[…]

Always—day after day—on the south-eastern horizon, brooded sullenly that curious stretched-out region of purple vapour, like the smoke of the conflagration of the world. And I noticed that its length constantly reached out and out, and silently grew.

Dillon’s website can be found here