Interview with Alejandro Yoshii

Alejandro Yoshii is an interdisciplinary artist whose defining act is the touch. We caught up with Alejandro a few weeks after he presented in A Mexican Tertulia at Baxter Street in collaboration with Celebrate Mexico Now.

Groana Melendez

Can you tell us about your artistic background? Do you have formal training in art?

Alejandro Yoshii

I came to the U.S. to study art, I did an MFA in Fine Arts at Parsons the New School. Before that, I studied Communications in Mexico and worked in advertising and graphic design. Painting was always part of my life, I was making paintings all the time but I didn’t have any academic training until I came here.

Once I started the MFA, I stopped painting and began doing other things. I think that happens a lot when you go to grad school. They challenge you to do something different than what you were doing before. I started doing more installations and sculptures and even performance. I’m exploring many different media now. I don’t feel myself fixed into a label of a painter or a sculptor. I like to work around the ideas and concepts and then later decide the medium.

Martha Naranjo Sandoval

What I like about your work is how it is so much about touch and it is also about you in particular, being there, touching something.

Alejandro

Like imprints of my body.

Martha

Yeah, you are like, “I was here, and this is my index of me being here.”

Groana

You even have a work titled “I am here.”

Alejandro

I know it sounds like a strong statement like I want to be in my work. When I went back to Mexico one time, I was talking with friends, and they reminded me of a prank I pulled in middle school. My class went on a field trip to a nature reserve and research center in Mazatlán, where I’m from, and I made an imprint by the lake there. I just drew this thing, like a footprint of an animal with six fingers. Later on, the teacher came to the classroom and said, “I need to know who did this because the researchers thought it was an actual footprint. They took a sample and sent it to Mexico City to investigate it.” Then they realized it was just a joke. The teacher was so embarrassed and wanted to know who did it. I had to confess that it was me. Maybe what I’m doing now, putting my body in my work came from this experience. I don’t know, but it was a funny and bad thing to do at that time.

Also, I kind of like to work around the body, and question the notions of the body and how we see ourselves and others. I think it’s related to my background of being Asian in Mexico. I’m Japanese-Mexican. People don’t see me as Mexican at first, and I have to explain that I was born in Mexico, but my family is Japanese.

Then, when I’m in Japan people see me as Japanese, but I don’t speak very fluently. There is always this sense of not belonging to a place, and the only place I think we truly belong is in our body. It’s like the only physical place we live and exist.

Groana

That’s so beautiful. I never thought of that. I’ve also made work about belonging and not belonging, and I never thought, “The place you do belong is in your body.” Can you tell us about your family background?

Alejandro

My maternal grandparents immigrated to Mexico before the Second World War. My grandfather came first, followed by my grandmother. My mom was born in Mexico, and she went to Japan to study marine biology. There she met my dad and brought him back to Mexico.

Groana

Oh, wow—I didn’t realize both of your parents are Japanese.

Alejandro

My mom is Mexican-born Japanese. Basically, I’m Japanese, but I was born and grew up in Mexico.

Groana

Do you ever go back to Japan, or did your parents ever take you?

Alejandro

I studied there for a year in high school.

Martha

How’s your Japanese? How do you relate to the language itself?

Alejandro

My Japanese got better when I was there. I speak some Japanese at home, like the term pocho but in this case mixing Japanese and Spanish.

There are many stories about the Japanese immigration to Mexico. In Chiapas, there is the little town of Acacoyagua that is the first place where Japanese immigrants settled in Latin America, as an organized immigration. It was called the Enomoto Colony. In the main plaza of this town, there is a memorial for the immigrants, on the back of it there is a haiku that says something like “summer grass, battles of the heroes, traces of a dream.”

I’m very interested in that. I’m going to Mexico in December, and I want to go to Acacoyagua Chiapas. I’m curious to learn more about it. There are some descendants of these immigrants and many people who have Japanese last names.

When my grandfather went to Mexico, he was single at that time. There was this thing like matchmaking for Japanese who immigrated to other countries. Most of the immigrants were single men, and they wanted to find somebody to marry, and I guess it was very difficult to marry a local person if you didn’t speak the language. The matchmaking process was done through photographs. My grandmother was told about this person in Mexico and was asked if she wanted to marry him, and she said yes. It was kind of like an old archaic version of Tinder.

Martha

With more severe consequences. You couldn’t just go out on a date. It was straight to marriage.

Alejandro

Actually, when my grandmother got to Mexico, she was already married. Her name was changed to Mitsuko Kasuga.

Martha

They married even before they met?

Alejandro

Yes. They even did a ceremony without the groom. There is a photograph where she is wearing a kimono and everything, but he’s not there.

Martha

A proper marriage?

Alejandro

Yeah, a long-distance marriage. When my grandfather came to Mexico, it was about ten years after the Mexican Revolution ended, and it was harsh times. They lived in San Luis Potosi.

Martha

Right now it’s a little better, but I can’t even imagine what it was like then. It’s not even like that big of a city now.

Alejandro

Water was scarce. My grandmother was shocked at breakfast when somebody brought her water and asked, “Do you want to use this water to wash your face, or for coffee?” She couldn’t have both.

After WWII began and Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Japan became an enemy of Mexico as Mexico was an ally of the US. The Mexican government gave the order to relocate all the Japanese people from the coastal and rural areas to the central part of Mexico, like Mexico City or Guadalajara, to have them close and monitor them.

It wasn’t as harsh as in the U.S. because they didn’t have concentration camps. (Actually, there was a small concentration camp in Queretaro.) My grandparents had already built a life in San Luis Potosi, and they had to start again in Mexico City, but it was good for them in a way. That’s why there is a big Japanese community in Mexico City. There is a Mexican-Japanese school and other things.

Martha

I was thinking about how circumstances forced your grandmother to move, but then you left Mexico by choice. You were like, “This is what I want to do.” I thought that was an interesting contrast.

Alejandro

Yes, my grandparents had a very difficult time, and now I’m in a more privileged situation. Their experiences are inspiring and a motivation for me. I always have it in my head and my heart.

I want to explore that part more. My grandmother used to write tanka poetry. They are short poems where she expressed most of her experiences, from the time she left Japan to her everyday life in Mexico.

Martha

It’s interesting that your grandmother was somewhat of an art-maker, even though it’s not visual art, she used art to help her process what she was going through.

Alejandro

I’m very interested in my grandmother’s poems about her life and what was happening around her. And the process of abstracting experiences and reducing them to verse within a rigid system of five, seven, five, seven, seven syllables. I like that idea of taking things from the world and reducing them into a short point.

Groana

How much of your practice is about performance?

Alejandro

I sometimes do performances. If I have a show with an opportunity to do a performance, I will. In performance, the body is the medium, the actions, the body and the remains are the work, but it’s very challenging to put yourself in front of a lot of people.

Some of the work I do with the traces of the body and the imprints has a residue of an action or a performative action—like painting the whole space with the body, or a wall. Performance is quite challenging, because you don’t know what’s going to happen, how you’re going to react, you’re vulnerable, etc. I’m very nervous before a performance, but when I’m doing it I kind of get lost and forget about it.

Martha

You’ve been talking a lot about Mexican-Japanese people, but the work you did on Ayotzinapa is more about a Mexican issue. It’s interesting how you embrace both.

Alejandro

I don’t mention it directly. I guess some of my work is a form of a silent protest. I made that piece after the missing 43 students, and when all the protests were going on in Mexico because of that. When you’re far from Mexico and you’re observing things from a distance, it’s difficult to address those issues, because you’re not there. You’re not experiencing it, but you want to talk about it. You want to make it visible for other people who don’t know about that situation.

I tried not to make political work that is in your face with blood and bodies. It was a performance piece where I ground cacao seeds and used the paste to make drawings that were instructions for actions and movements.

I was thinking of the number 43 in relation to the body and in this case bodies, and movement, in relation to the social mobilizations to protest against this criminal incident. So I had these three elements: body, movement, and symbols. The drawings on the wall became an accumulation of these repetitive actions.

And when I was grinding the cacao, the smell of cacao permeated the whole room in the exhibition space.

Even if you don’t want to talk about political issues, you inevitably end up addressing them—it’s something that we experience every day.

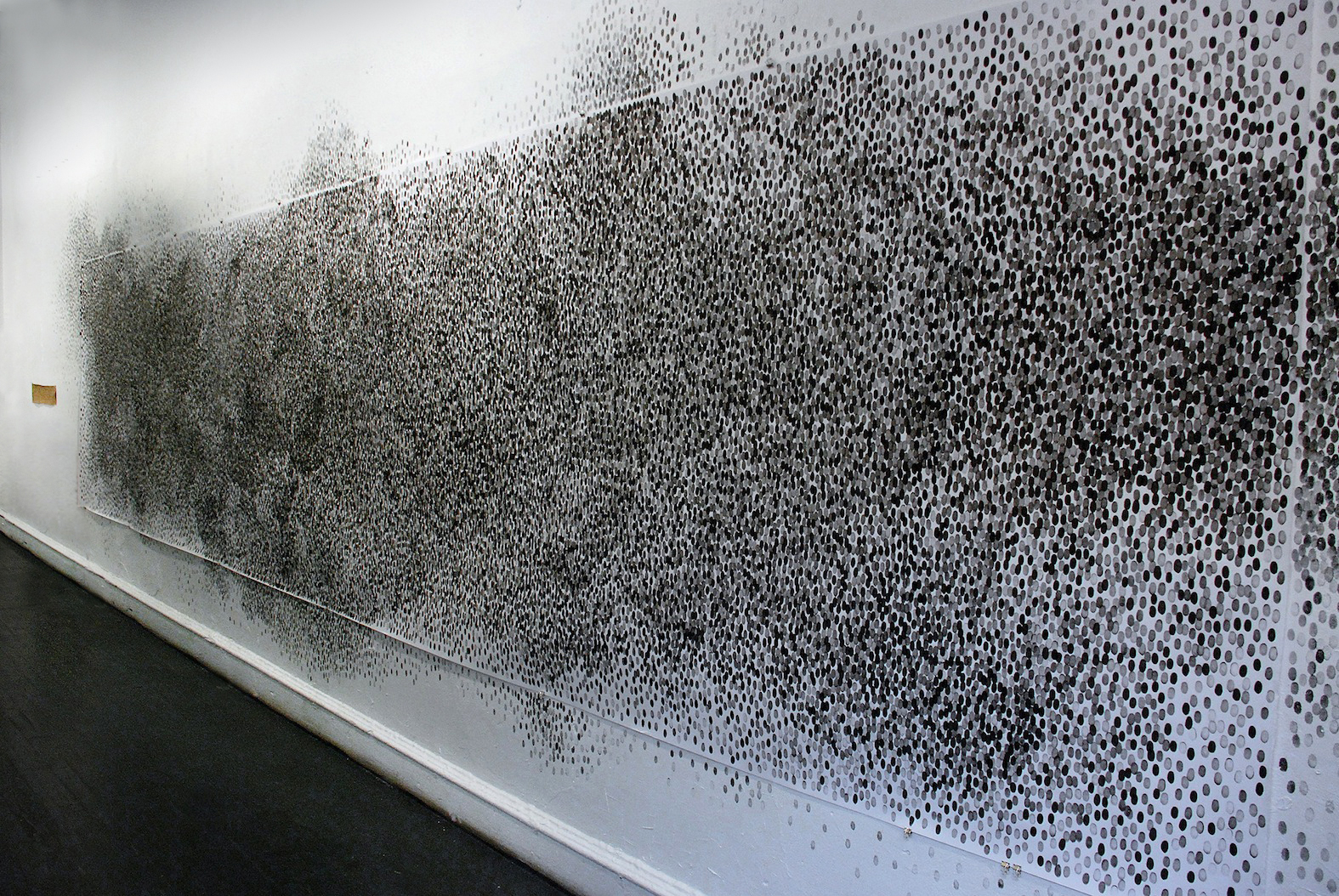

I have another work that is a big piece of paper with 47,515 of my fingerprints. I read an article in the New York Times stating that at the end of the Felipe Calderón presidency, the official number of murders from the drug war was 47,515. There were obviously more than that, but I wanted to recount all these numbers and make them visible. I counted each of the 47,515 fingerprints. I like to make work that can be grounded in political issues, but in a more poetic way, visually.

Martha

Which is very nice. I think about someone like Teresa Margolles and What else could we talk about? She talks about it in a way that you as a viewer are somewhat forced into violence. I like the way you approach it because it’s still very visible, but it’s not so violent.

Alejandro

Yeah, I don’t think I would like to attack violence with violence. My work is not so graphic. I think I try to find ways to say things that are around my life, in a non-aggressive way I guess. I just take things I see. If that is what I see and experience, I need to put it out there.

Martha

I can understand, because when that happened, I was here in New York. All of my friends, all the people I knew, were protesting back in Mexico. Protesters were even getting arrested, and I was here looking at it on my phone. I went to Union Square, and there were like three Mexicans there. I felt so weird not being back home.

Alejandro

I know what you mean. I make art, but if I also want to do some activism, then I do it. Artwork may come from political issues or family stories or other experiences, whatever is informing my work at that time.

Groana

What does your practice look like? Your daily practice?

Alejandro

I sometimes start by making sketches and drawings. I like to make quick drawings with watercolor, and sometimes more detailed sketches. I like to put them around on the walls and have them visually in front of me, and see them every day.

What I like about this process is that when I start making and object or something, I later find similarities to the things I did a long time ago. It’s a way to create your own visual language.

Then I also have to do my freelancing jobs in graphic design. I have to pay my bills you know, but I have flexibility with time, and I’m able to work and make my own artwork, but my schedules are a mess sometimes. I guess that’s my system of working or process, having all these visual elements and then trying to make connections around them.

Groana

Can you tell us about your most recent shows, especially the one opening tomorrow (December 9, 2016)?

Alejandro

The one that is tomorrow is a post-election show and related to the winning of Trump, part of the proceeds will be donated to the Center for Reproductive Rights and the Southern Poverty Law Center. It’s for a good cause. I made the smallest sculpture I’ve ever done. I’m responding to Trump and the wall, and also referencing the body.

The show that opened a few weeks ago was more of an installation. I wanted to do something intersecting sculpture, drawing, and installation. I had these prints of my body, my arm, leg and foot, and printed them life-size on metal. I use them as rulers, with them I measured and cut the pieces of wood to make the structure, kind of like tables. The objects I had on top were also imprints of my body, mostly of my hand, and then I drew the surface of the table. I had all these mix of things, everything around the body, like deconstructing my body and constructing something else and occupying the space.

The Palace at 4:20 am (2016) Plaster, graphite, pencil, raw hide, black gesso, bone black pigment, whitewash, magic sculpt, wire, wood, digital screen print on dibond.

Martha

It reminds me of the measuring system they use in the U.S., which was basically the king’s measurements. Like a foot was the length of the king’s foot.

Alejandro

Yeah, I decided to make my own system of measurement based on the body.

Groana

What are you working on now? I know you mentioned going to Mexico, to Chiapas.

Alejandro

Yeah, that is totally different from what I’ve been doing, more personal. At this point, I’m researching and studying more the history of the Japanese immigration to Mexico.

Immigration is something that happens all the time, and shifts certain structures in the world, socially, culturally, politically. I think it’s important to talk about all these in order to bring more diversity, I guess.

It’s funny, because now that I’m in the U.S., I’m interested in things from back home. Every time I go there, I gather more material. My parents are marine biologists, and they have all these old biology books. I remember looking at them when I was a child, but now as they don’t use them anymore, they told me I can do whatever I want with them, so I’ve been tearing them up and making collages, I love these images of shells, fishes, plants, etc.

Martha

That makes sense. I was never interested in the pictures that my parents took of me. But when I came here I was like, “I want to scan all of them, and do work around them.”

Alejandro

Yeah, there is some kind of nostalgia, no?

Groana

You have to step away, in order to see your life. That’s the whole reason we want residencies, right? We need to step away—not only to have the time to focus, but also to reflect on our lives.

Alejandro

To reflect and see the things from outside. I think that to get deeper into your thoughts, you have to step back a little bit and see yourself from the outside.

Martha

I think it’s very hard to focus on things when you have them so close to you. It’s easier to see them clearer when you step back.

Alejandro

You don’t see them. You take them for granted because you have them and you’re just like, “What else can I do?” You try to make things outside your bubble. Now, when you’re outside the bubble you’re like, “Oh, wait, I can see what is in the bubble.”

Martha

You don’t even think it’s interesting because that’s just normal life to you. When you’re outside, you realize normal life is not even a thing. And besides, that’s actually what you can talk about more, because that’s what you know about it, whatever else you are a little bit clueless, but your experience is your best topic. All of our experiences are so different that it’s important to say, “This is what it looks like to have my life.”

Alejandro

And in New York, there are people from all over the world, and everybody has different experiences in life. It’s interesting, what happens here, the conversations that happen here. Everything is around our roots, and that’s important. It makes you see that the world is more diverse. And on the other side, you don’t want to assimilate into another culture and lose your roots, because you want to keep your voice and keep your background.

Martha

There’s one part of you that really wants to fit in. Back in Mexico, I was rebellious, so I never had a quinceañera. Now that I’m here I’m like, “I wish I had had a quinceañera. I wish I had more of an accent, and I wish that I wish I was more Mexican,” whatever that means. When I was in Mexico cumbias were cool, and I will dance them at parties but never listen to them in my own time, but now I’m like, “Oh, I will listen to them in my house,” but that never happened before. It’s not like I really think there is such thing as more Mexican, I guess what I mean is that I wish I was part of a community of Mexicans here, I miss that familiarity.

Alejandro

Actually, that happens to me too. In Mexico, I feel like I need to assimilate more to the culture, and have a strong accent, in a way to prove that I’m Mexican. It’s like an identity play. Belonging and not belonging is confusing. It’s just a back-and-forth situation, of trying to find your place in the world.

Groana

What’s your relationship to photography?

Alejandro

In my practice I use photography to gather images, to get a collection of things that I see and captured my attention. Even if I take a photo of a chewing gum on the floor or something, it’s because it was interesting to me at that moment.

Recently I started printing my photos. I printed about 200, and I like to have them next to my sketches on the wall. Photography is my source material. Sometimes it helps me remember what I saw and what captured my attention.

Even if I don’t use them as artwork, they inform my work in a way. I like to take many photos of random things. I did a series of photos of only circular shapes, like a circular entrance or a circular object. I have many photos of that, and of sleeping dogs. They are part of my personal archive of visual images. I think it’s important for every artist to have visual archives.

Groana

Yeah, it becomes your library.

Alejandro

And accessible. That’s why I like to print them. Sometimes I make small sketches and forget about them. Now I’m forcing myself and put all of these images in front of me. I love that later I see them manifested in a similar form, but in another material. Like abstracting something from reality into a sketch and then transforming that into something else in another work or material. It’s like a filtering process.