Interview with Erica Baum

Erica Baum is one of the most intriguing photography artists working today. Baum’s scrutinizing of optic limitations images and words perpetuate bears riveting results, in which their commonly attributed potentials shatter to unravel new territories for ‘looking’. Experiencing her Naked Eye, Dog Ear or Card Catalogue series, viewers discover new scenarios, where the notion of gazing is redefined.

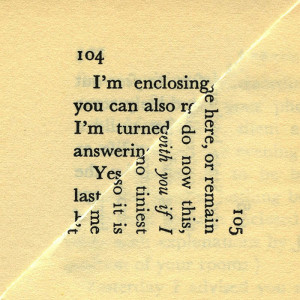

Using found sources including paper back books or index cards, Baum charges existing materials with uninvented narratives. Gestures such as folding or flipping aid the artist to build these alternate possibilities: a poem comes to light from the folded corner of a book revealing the otherwise covered next page or two curious eyes staring from a black and white noir with beamingly colored edges catch a sight of their onlooker. I’ve had the privilege to ask Baum a few questions about her striking practice:

— In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes separates photographic experience into two categories: studium and punctum, comparing the shift from the first towards the latter to an arrow piercing into his chest. Your works seem to stem from studium, which refers to firsthand informative or documentary photography, and transform into what Barthes would define as the subjective and capturing state, which is punctum. How do you see your creative process in response to Barthes’ concept?

My source materials, printed matter, linguistic and typographic traces of systems and structures reflect the circulation and dissemination of information in our shared popular culture. This is the ‘studium’.

I navigate intuitively, trying to corral and align my designated variables harnessing moments that suggest meanings beyond their original situations. The act of selecting and partially de-contextualizing the images could be considered the ‘punctum’. This is when the encounter with the subject transcends the ‘studium’. But there’s always a dialogue between the two.

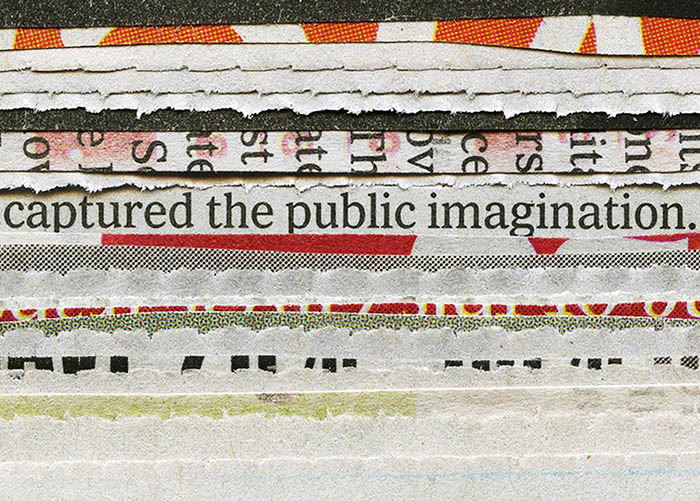

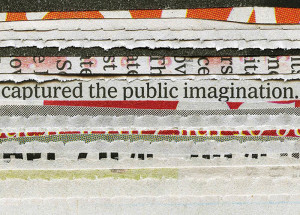

— Naked Eye Anthology, Dog Ear and Newspaper Clippings series all manifest performative associations with paper, involving various acts such as flipping, folding or cutting. In other words, you engage with the tactile quality of paper as much as you do with its utilitarian component of storing information or image. What does paper mean to you in terms of signifying a territory to constantly revisit?

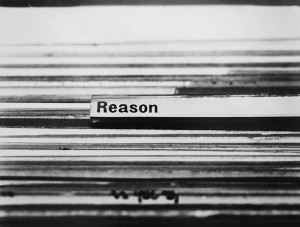

I’m looking for language in a visual field and most often it’s paper that provides that field. In one of my earliest series, ‘Card Catalogues’ I became aware of the hands behind the system. The librarians’ hand shaping and organizing and the researchers’ hand, pulling out files and rifling through cards. When I started that project in the mid 1990’s, it was intended to reflect a quotidian relationship to the library. But very quickly it became clear to me that libraries were decommissioning the card catalogues replacing them with computers.

In the ‘Dog Ear’ series I draw attention to the act of folding down a corner to save your place in a book. These moments spontaneously generate new experiences of language and meaning. They are specific to physical books rather than ebooks. Paper in both these cases provides a space for a physical encounter that can be captured photographically.

— In your work, you celebrate the power of words; however, you also strip them off of their traditional raison d’être. They no longer stand to ‘define’ or ‘mean’ what they originally did. Elena Ferrante calls prose a chain that pulls water up from the bottom of a well. Do you think you break this chain or rearrange its rings?

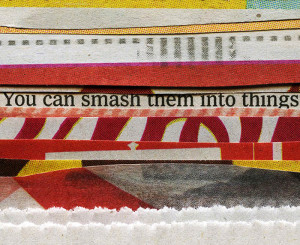

Often I’m treating words as things to be rearranged and repositioned exacting new meanings, not nonsense but a different sense. I always include enough photographic description, texture dimension, to allow an aspect of the original source to linger consciously.

— Your practice involves peeling off an image or text in order to juxtapose undiscovered narratives. Do you think those narratives are already embedded in there or you create them anew? In other words, how do you define the difference between looking and seeing?

I’m often drawn to photographs of people expressing an emotion, appearing to think and consider. In the ‘Naked Eye’ series this collection of images becomes a kind of indexical typology of narrative types, incomplete and non comprehensive, suggesting narrative rather than creating specific narratives and in that sense relates to narrative as a structure composed of types similar to the collection of types of art in my ‘Frick’ series and types of categories and subjects in my ‘Card Catalogue’ series. Hopefully the ‘looking’ and the ‘seeing’ are inextricably tangled up.

— As an artistic practice, photography is already far from solely ‘capturing’ the moment. In line to its merger with Conceptualism, photography is susceptible to issues surrounding conceptual art—visual narrative, practical execution and aesthetic challenges just to name a few. How do you see this dialogue between two disciplines?

Conceptualism is a part of all artistic practice. Whether consciously by intent or consciously in it’s reception there is always a platform where meaning resides.

*All images are Courtesy of Bureau and the artist.