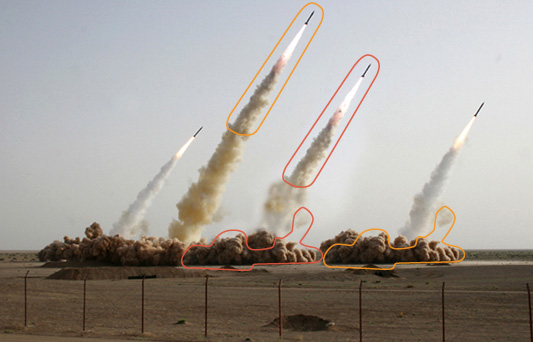

Jennifer in Paradise

If you’re something of a Photoshop nerd you might recognize this image “Jennifer in paradise” as that taken by John Knoll of his then-girlfriend Jennifer in 1987. John was working on a cheaper alternative to highly-priced imaging software. Since digital images were not easy to come by (it feels weird to even type those words) John used a scanner (also not easy to come by in 1987) to digitize this photo, which was all he had on him at the time. The software that John was working on would eventually become Adobe Photoshop, and the rest is history. Even in version 1.0, the software is impressive in what it can do, as John shows in this recreation of an early demo:

With this development in software, users could install and operate Photoshop on consumer-grade machines rather than pay for time (up to $900/hr) on hardware-based imaging applications. The democratization of digital image editing we know today started here, and Jennifer in paradise was the first proving-ground. Artist Constant Dullaart made it the subject of an exhibition in London a few years ago, and this open letter to Jennifer is worth a quick read. Although John himself doesn’t find the project particularly interesting, as this Guardian article notes, Jennifer is nonetheless inextricably linked to the history of digital imaging.

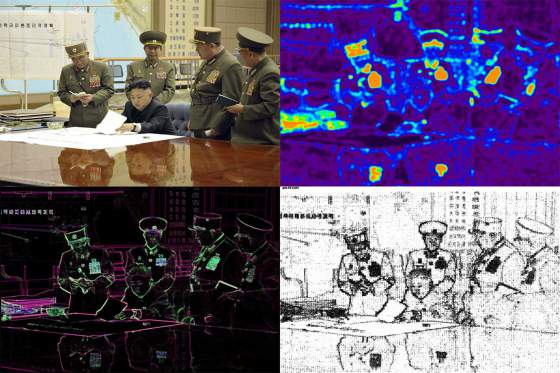

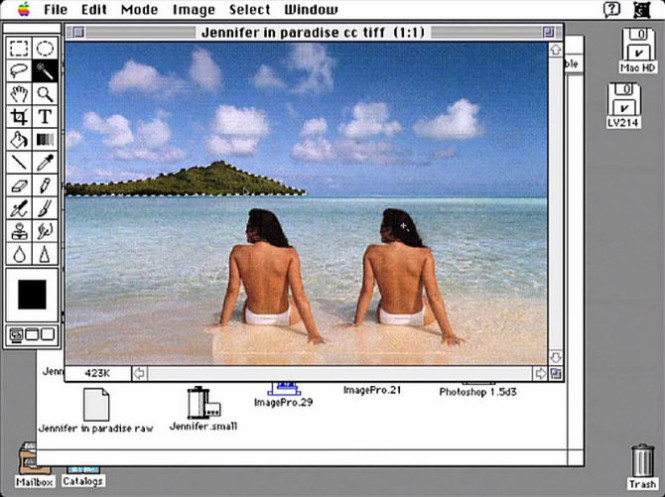

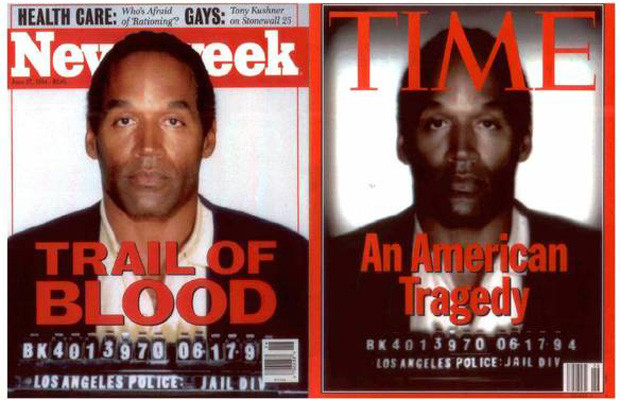

In a post last month on ArtSlant about Dullaart’s work with the Jennifer image, Edo Dijksterhuis argues that there is no overriding moral imperative that prevents us from altering images, with a couple minor exceptions. He cites the World Press Photo competition’s rejection of 20% of it’s entries on the grounds of their being digitally altered as one example of manipulation that is frowned upon. Another example is the widespread practice of restructuring the female body in advertising. Dijksterhuis says that we collectively disapprove of these particular offenses, but by and large we accept and condone the prospect that every image has been altered. But…is that really the case? Resigned acceptance and complicity are not necessarily the same thing, to say nothing of approval. We certainly don’t accept or approve blatant manipulation in the political arena (when we can prove it). This was the case when Russia provided altered satellite images as proof of Ukrainian involvement in the downing of Flight MH17 (twice). This was also the case with Iran’s or North Korea’s doctored images of missile launches. It was not acceptable in 1994 when Time magazine (unintentionally, according to them) published a sinister-ized mug shot of OJ Simpson on it’s cover. And on a far more banal level, I doubt most people accept it in online dating profiles either. And for every instance that gets called out, how many more do we miss? Are we ok with that?

Comparison of O.J. Simpson’s mug shot on the cover of Time and Newsweek in 1994

This is, of course, not to say that digital image manipulation is inherently wrong and should be socially unacceptable. Rather it points to the fact that we as consumers of images haven’t really figured out what we want from photographs, or how to reconcile them with our ingrained notions of truth. We want photographs to be both objective and expressive. This is a prickly issue much larger than a blog post can fully address, but the question of our expectations from photographs is less resolved today than it ever has been in the past. Photography’s dual-citizenship allows it to seemingly offer hard-truth objectivity on one hand and speculative fabrication on the other. Which of course makes it the perfect medium for politics, which are often bound up in the same contradictory elements of aspiration and pragmatism, particularly when these emotions are entwined with images of war. Take the story of the famous flag-raising on Iwo Jima by the US Marie Corps in February 1945, just over 70 years ago: The iconic image on which the memorial in Washington D.C. is based was the second flag raising that day. Marines were ordered to remove the first flag because it was too small and could not be seen from the beaches.

The second, iconic raising of a larger flag, photographed by by Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal

In her book Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag describes the second flag-raising at Iwo Jima by stating that “With time, many staged photographs turn back into historical evidence, albeit of an impure kind – like most historical evidence.” She goes on the claim that actual staging of events largely ended with the Vietnam war due to an abundance of photographers (I for one am not convinced this is true), and conceded that the possibilities for post-production manipulation are much greater as technology progresses. In the same book she traces the history of staged photography in war all the way back to the Crimean War in 1855. She describes a scene in which photographer Roger Fenton allegedly altered the landscape of a battlefield to make it appear more dangerous. Documentary filmmaker Erroll Morris — in an effort to find evidence for or against Sontag’s unfounded claim — wrote an opinion piece about the photographs in the NY Times in 2007 but it’s much more satisfying to listen to him talk about it on Radiolab.

Animation showing that rocks had rolled downhill between the first and second photographs. Proof for Morris the the second image was staged

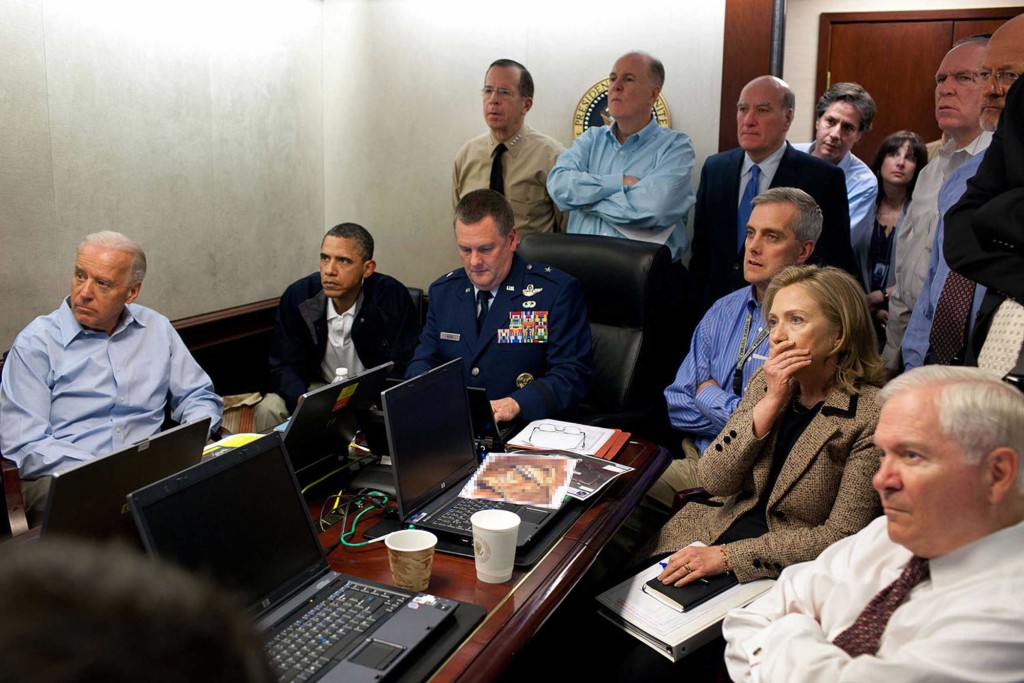

More recently, the images surrounding the raid that killed Osama Bin Laden in 2011 have their own set of photographic uncertainties. Faked images of his body were published in major news outlets before being discovered as fraud, but these images still circulate widely on the internet (I’m not linking to them, but a google search will bring them up easily should you want to look). And while that image is clearly not authentic, even the more verifiable image of the “Situation Room” in the the White House taken during the raid itself highlights the way politics takes advantage of photographic ambiguity:

The image itself is both gripping and evasive; we don’t know what they are looking at (is it the downed helicopter? Or the ensuing gunfight? Maybe the signal was lost and they’re simply waiting for it to return?). Ken Johnson in the New York Times went so far as to describe Hillary Clinton as Roland Barthes’ punctum, her hand covering a repulsed gasp. But…she also said she had allergies that day and was probably just stifling a cough (maybe it was even a yawn?) What can we make of that? Do you read that image differently now?

So while we know and resign ourselves to the fact that manipulation is and has always been part of photography, where do we go with that knowledge? Perhaps the most insightful approach comes from a computer engineer, Roger Cozien. Cozien developed Tungstène, an image-analysis program that is used to detect digital manipulation of photographs:

(WARNING: the faked bin Laden image appears at the head of this video, so skip it if you don’t want to see it!)

In a recently translated article, Cozien has strong words for the World Press with regard to the vague rules regarding manipulation in their entries, calling their rules “nonsense”. Taking a look at the actual guidelines of the world press photo competition, Rule number 12 under the Material Specifications says, “The contents of an image must not be altered. Only retouching that conforms to currently accepted standards in the industry is allowed. The jury is the ultimate arbiter of these standards.” In other words, “we’ll know it when we see it.” Cozien is worth quoting at length when it comes to the question of truth in photography:

We are all mistaken in considering that photography is the witness of reality. It’s wrong. Photography is a way for the photographer to express himself. The question is not: “What does the photograph show?” but: “What did the photographer mean?” Take a photographer coming back from Nepal. His speech will be very emphasized: “I was in Nepal, it was dreadful, unbelievable, horrifying!” Someone writing a press release using those terms will not be told: “Sir, you said it was dreadful but it was not, it was only tragic.” We never have this type of reflection. We never blame a journalist or a witness for using an inappropriate word. However, a photographer saying: “I saw a fire. My photograph was not representative enough of what I saw, so I darkened the smoke to give it a more terrible effect.” Why would this photographer be more blameworthy than someone who used some words to report an event? When the photographer modifies his photograph to show us, who were not there, the extent of what he saw and which was not depicted in his photo, is his action reprehensible, blameworthy? Is it legitimate?

This perspective is especially compelling given that it comes from a man whose career centers around raw computational data; he is not a photographer or an artist who takes advantage of ambiguity in his work, his work deals with unequivocal numbers and mathematical analysis. And yet when it comes to how we should approach photography, and what we should expect from it, he considers photography the exclusive domain of individual expression in precisely the same way that language is. He’s even working with a specialist in semiotics on a book addressing these issues in photography. In his view, if we want truly “neutral” images, we should get rid of human photographers (easier said than done) and allow it to be done by machines. That’s an issue for another day. Cozien thinks that we should respond to photography (all photography, not just art) in much the same way that we respond to the written word; take it all with a grain of salt, but a tweak isn’t necessarily a lie. Because there’s no reason to expect that this form of expression will be anything but easier and more accessible in the future. Adobe is still working on ways to allow photographers to manipulate their images on the go:

So with that said, feel free to hit the beach, because soon enough you’ll be able to make a perfectly expressed twin-copy of Jennifer before your feet leave the sand.