Keisha Scarville, The Placelessness of Echoes (and kinship of shadows), by Daniella Rose King

There is a poetry and lyricism at work in Keisha Scarville’s photographic and mixed media series Placelessness of Echoes (and kinship of shadows). It appeared in the narrative assembly of works across the Camera Club of New York’s white walls. The images lean on, extrapolate, and depart from the words of Wilson Harris, Jamaica Kinkaid, the artist herself, and other writers who have sought to explore the complex interplay of subjectivity, place, and power. Placelessness of Echoes… speaks of landscapes that are alive, possessed, and have stories to be told.

Untitled (topographic map), 2018

Journeys – both metaphorical and actual – are the foundation of Scarville’s artistic inquiries. Whether tracing her parents’ migration from Guyana to the United States (Passports); addressing her mother’s passing through material ciphers and their potential to conjure (Mama’s Clothes); or the excursions undertaken to produce Placelessness of Echoes… movements that transform bodies and individuals are explored by Scarville’s photographic gaze, in images that convey texture and shadow in seemingly impossible ways. Placelessness of Echoes… luxuriates in darkness, simulating the experience of an eye adjusting to the lowest levels of light. The series is performative and process-oriented; from scouting, to returning to traverse and negotiate the chosen terrain, to camping, observing, and engaging in the discrete and little-known rituals Scarville created to capture her photographs – this body of work meditates on time, place, and space and how each informs, overlaps with, and produces the other.

The “placelessness” of the work’s title, calls attention to the paradox of space, of how the wilderness confounds our attempts to command, locate, and describe it. The landscape in Scarville’s photographs refuses to be fixed in place. Further, the composite nature of the series, staged as it is in numerous, unnamed topographies, is quietly suggestive of the un-geographic facts of Blackness. (After all, where is Black?) To be dispersed, located, placeless, and out of place – all at once.

Untitled (River), 2017

With her camera – a tool for fixing in place and measuring time – Scarville creates bifurcating narratives of a black female body in and of its rural surroundings. In these we see how the landscape lives in the imagination of the artist – and how perhaps, it stands as a signifier for other spaces. One of these is the fictive space of Harris’s Mariella, the territory in Guyana that is the setting for his novel Palace of the Peacock. Another is the idea of a landscape at night, that in the artist’s words, “becomes everywhere and nowhere, occupying multiple spaces at the same time.” This sense of multiplicity and hybridity is intimately tied to subjectivity’s constant process of formation, and how these transformations are prompted and determined by spatial paradigms. For Scarville, the series is a way of decentering the body in thinking about place – resisting the urge to describe it as a dichotomy of body and nature, instead to think, in Katherine McKittrick’s words about “how bodily geography can be.”

The scenes created by Scarville are the diametric opposite of the cityscape, that which is constantly illuminated, surveilled, and controlled; these qualities programmed into its very topography. As such it is largely vacated of mystery, intrigue, darkness, and the unknown. For Black Americans, experience has taught a suspicion and fear of rural landscapes for the stage they provided for acts of racial terrorism; from lynchings and slave blocks to centuries of uncompensated and cruelly-cultivated labor all carried out on stolen indigenous land. Adversely, the landscape (especially at night) evokes stories of refuge and sanctuary, it conjures the fugitives who traversed the land in the era of the underground railroad. Scarville’s series captures glimpses of the ghosts of those whose self-emancipatory journeys are etched into the land. Making space for the unknowable, mystical, perhaps even magical qualities of the landscape at night mirrors the very capaciousness of the land, and seeks to recuperate the Black female body in nature. Partly through the guise of the shapeshifter – a central figure in Palace of the Peacock, and across a selection of Kincaid’s short stories – she is at once a metaphor for the placelessness of the Black female, the diasporic figure, and a vessel through which the individual navigates, commands, and is enveloped by space.

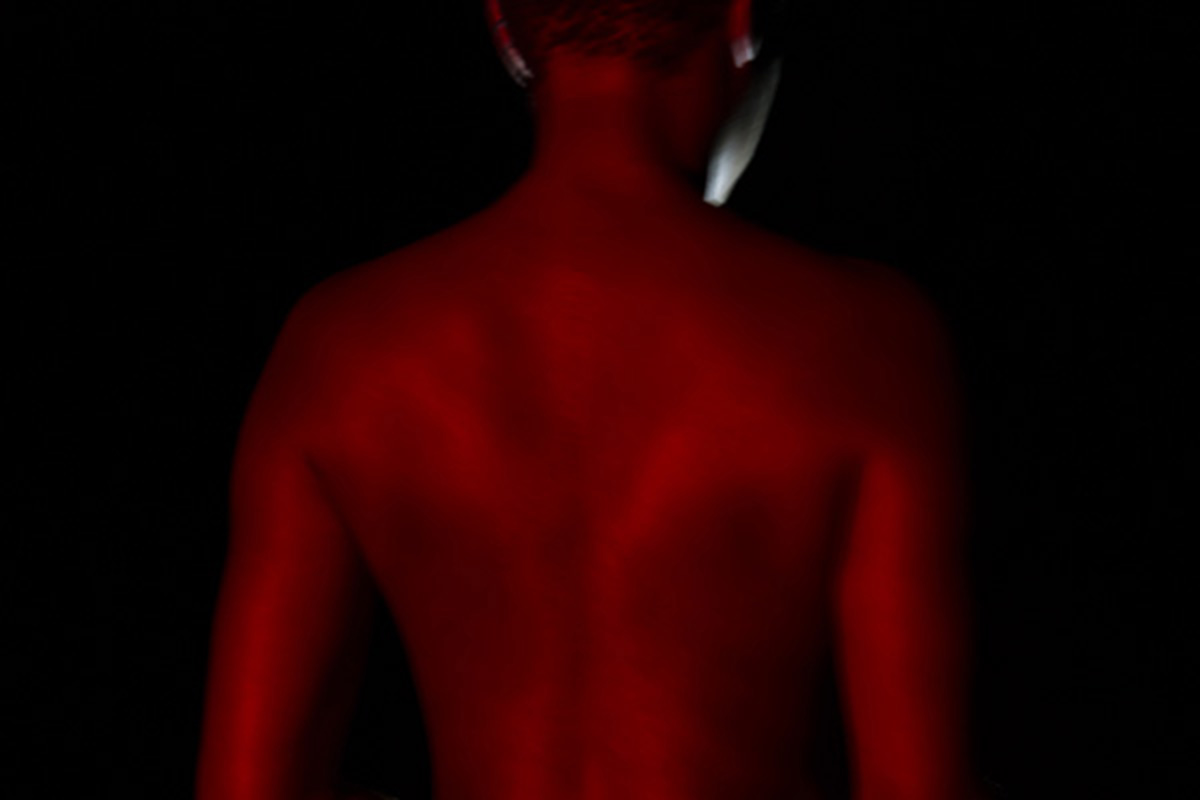

Untitled (back), 2017

In a number of images, we see a woman’s body, and the foreground and ground illuminated by red light; chosen in part as it is invisible to most nocturnal animals, and therefore undisruptive to their nightly pursuits. These strongly invoke traditional spiritual practices of the Black diaspora, themselves radical acts of resistance. They also call to mind the mystic or the witch – a maligned figure, whose roots are located in the first anti-capitalist struggles of feudal Europe and the newly-colonized Americas. Scarville’s photographs allow us to grasp and consider the complicated embodied history of the landscape: as a terrain of many terrors, as a fertile ground for growth, a place of imagination and becoming, and a setting for kinship and community.

Untitled (topographic reimaginings), 2017

– Daniella Rose King