Sarah Palmer’s No Whiteness Lost

This week I had the pleasure of meeting with photo-based artist Sarah Palmer. Here in her studio at The Invisible Dog Art Center, Sarah arranges, photographs and re-photographs small assemblages to produce thoughtful, highly literary images. For me, Sarah’s insights into photography, literature and her current project, No Whiteness Lost underscore the importance of continually connecting with and learning from other artists.

Liz Sales: You have so many Polaroids here!

Sarah Palmer: I have hundreds more. I shoot 4×5 film with strobes, so Polaroids or, these days, Fuji Instant packs help me to pre-visualize my images. A photograph is such a different visual experience than real-life seeing.

Liz Sales: But these don’t always serve a solely utilitarian purpose, do they? You include Polaroids in your still-lifes —for lack of a better word.

SP: Yes,I like to include photographs as physical objects within my images. I think of them almost at mirrors that reflect inward, eliminating the elusive “viewer,” creating an almost disturbing psychological space.

Mirror Dance, 2014

LS: Is this something you’re exploring currently?

SP: Yes, in many different ways. I’ve been slicing up old prints and putting them back together. For example, this is an image of a balloon that I composited with a Hubble Space Telescope image of the birth of a star. I took the same image, inverted it and printed that, as well. I combined the images and re-photographed the collage. There is this hard shadow, cast onto the background, which a real balloon would never make. I think this non-indexical quality widens the gap between what an object is and what an image of an object is, which is an important idea in my work.

Nursery (Carina), 2014

Liz Sales: So, this is part of a larger body of work?

SP: Yes, this series is called No Whiteness Lost. I borrowed it from a line in The Descent, a poem by William Carlos Williams. He became one of my favorite poets, when I was studying literature in college.

LS: I’m not familiar with The Descent. Could you tell me about it?

SP: Williams wrote, “[N]o whiteness (lost) is so white as the memory of whiteness.” He wrote this poem as an older man, and, to me, it really articulates the way memories transform as time passes. I don’t remember events as vividly as I remember feelings and emotions. If you asked me about a novel or a film, I would be more likely to recall how I felt when I read or watched it, the color or formal elements, the music and the tone, than the plot. That’s why I’ve appropriated No Whiteness Lost as the title for my series – I’m interested in making pictures that create color/form, “music,” and tone rather than narrative.

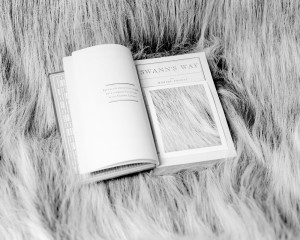

LS: That resonates in Object (Swann), which references Proust’s idea of the fallibility of memory. Are literature and poetry significant to your work in general?

Object (Swann), 2014

SP: Yes, text is always significant to my work. While making this work, I’ve also been thinking about the lead light and empty horizons – a sense of ecstatic futility – in Beckett’s Endgame, as well as the whiteness of Melville’s white whale, as a metaphor for horror.

LS: Whiteness as a metaphor for horror in literature often references Colonialism and racial dominance. Is that idea relevant to your work as well?

SP: That is quite a complicated question for me. I resist the didactic in my work. I am politically concerned but have a complex relationship to activism, and I struggle with how to engage these issues in my work. Perhaps this will change over time, as I mature as an artist. Photography is such an easily illustrative medium and I thwart clear narratives; rather the “whiteness” I reference here has the power to blind with glare, to obscure, to create blank space.

Hence, I tend more toward philosophy, looking at artists and poets who explore ambiguous spaces, including Williams and H.D. among Modern poets; Samuel Beckett; my father, the poet Michael Palmer; the poet Robert Duncan and his partner, the artist Jess, (both were close friends of my father’s); the poet and painter Norma Cole, (also a friend).

I’m also drawn to contemporary artists who engage with photography in fascinating ways, including my husband Dillon DeWaters, Sophie Ristelhueber, Viviane Sassen, Gabriel Orozco, Sigmar Polke, R.H. Quaytman (herself, the daughter of a poet, Susan Howe), Leslie Hewitt (whose work engages in a fascinating way with history), my friend Lucas Blalock, the brilliant Paul Chan, Lorenzo Vitturi, whose work I just discovered, and I could go on for pages and pages. It is really important for me to be part of a community, even if is a community of influence, artists I don’t know. The smallness, the inter-connectedness, of the world makes it more engaging to me.

A Shadow is a Shadow, 2015

LS: That reminds me of a conversation I had with Dillon. He also stressed the significance of being part of a community of influence and the importance of artists, filmmakers and writers being in conversation with one another through their work. How does being married to and sharing a studio with another artist influence your practice?

SP: Dillon’s and my work are hugely influential on one another. When we met ten years ago, we were in love with photography, with the history of photography. For both of us, that relationship to photography has evolved and developed, has transformed, really, into a more complex and interesting one, into an art practice. Both of us have moved away from more traditional forms of photography, into ourselves and our psyches, finding sources in other artworks rather than just in the field. We also have a son now, which makes an art practice both far more difficult and incredibly, more necessary. We have had to make peace with our pasts, so to speak, and in my case, that involves embracing my love for words and the way words make my heart race, create electricity in my head. That’s what I desire from my work.

Polke 1969 (Perfume Picture), 2015

We also end up photographing the same subjects, from time to time, on our own. We are actually on the cusp of releasing an ongoing series of limited edition diptychs, Pyramid Editions, one a month in 2015.

LS: Congratulations! It’s also note-worthy to me that you mentioned empty horizons in literature earlier. I’ve noticed that your images tend to obfuscate the horizon line. For example, in A Spiritual Urgency, an empty stepladder seems to exist midway between Earth and the stars, with no distinct horizon line separating the two.

SP: The ladder is actually surrounded by fake “snow” which I created by blurring stars photographed by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. I have a memory of being backstage at the ballet while they were testing the fake snow for The Nutcracker—snow falling on an empty stage. It was thrilling, and it stayed with me.

A Spiritual Urgency, 2013

LS: That sounds like a wonderful memory, and hearing about it adds a tenderness to the work. Are you a romantic?

SP: I’m a bit of romantic, but not (I hope) a blind romantic. I’ve thought a lot about the Sublime, ever since reading Edmund Burke as an undergraduate, and have been searching for that heart-stopping and wonderful-terrifying moment, looking over the edge of the cliff (hence, Endgame, Moby Dick, The Descent – apocalypse, horror, facing inevitable death). As a result, my scale has gotten relatively small; I used to make landscape photographs.

LS: I don’t understand.

SP: In my graduate thesis, I was searching for the sublime in America to see if it still existed, post-railroad era—

LS: Oh! Does it still exist?

SP: Nope, not in the German Romantic sense. So, I started to explore the sublime inside my studio, and my scale necessarily condensed.

Control, 2013

LS: It’s definitely worked out. In contrast to the small scale you’ve adopted primarily, you also appropriate astronomical images. Could you talk about your interest in space?

SP: What could be more terrifying than the vastness and unknowability of the universe and time, and our relative infinitesimal tininess? The terror I first felt at the idea of non-existence was not dissimilar from the terror of space and infinity, both around age 9. And yet, the Hubble has made these incredibly beautiful, knowable, picturesque images available to us. Even if they are romanticized data approximations, they are so late-80s and fantastic. Black light posters and smoke machines and raves. All-night dance parties.

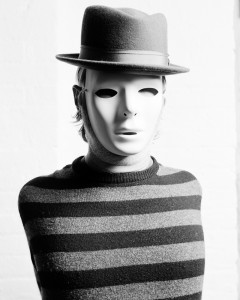

LS: You’ve found a tension between fear and pleasure, which I associate with the sublime, especially in your depictions of people. Could you talk a bit about your decision to seat your subjects facing away from your camera?

SP: That’s a very good question. I rarely photograph people and I’m not interested (in this work, at least) in making portraits, but people have this inescapable quality, a particular-ness, in photographs. And, therefore, there is something horrifying about removing their faces, which I do with hair or masks or simply by turning them away from the camera. I like to treat people no differently than I would treat any other object in my studio.

Wove out of the dark, 2012

LS: I’ve noticed that you often use studio supplies, like ladders and buckets, in your work as well. Is that in reference to the artist’s process?

SP: I work intuitively and don’t have preconceived notions going into the studio, so I tend to use what is available. Also, I love the idea of turning something mundane into something uncanny or unrecognizable through context, use against purpose; re-examining ordinary objects, and somehow through that examination transforming them into something radiant. For example, people tell me this image, No Horizon, looks like a scribble, but it’s actually a photograph of gathered tulle.

No Horizon, 2014

LS: Oh, I did think that might be a photograph of a drawing!

SP: That’s what I love about tulle! It responds to light in a way that causes it to appear blurry or unfocused on camera. I’m always fighting against the inherent representationality of photography. It’s an absurd and impossible struggle; photography literally re-presents reality. I’m using a medium that is intrinsically representational, and I’m trying to move away from representation.

LS: That’s interesting, because even though you are pushing against the medium in many ways, I find your work to be inherently photographic, or at least self-reflective.

Red Burn, 2014

SP: Oh absolutely, this summer I started a project, making contact prints on construction paper, by leaving 8” x 10” negatives on the paper out in the sun. So, even when I am not using traditionally light-sensitive photographic material, I am still referencing photography. Literature and philosophy are important to my work, but it is always still rooted in the medium of photography.