saying what you can’t say

My job is not to produce answers. My job is to produce good questions.

Glenn Ligon

This is my final post 🙁

It’s a conversation with myself and two artists: Dalia Amara, a friend, and Randy West, my first crit prof at SVA. What really stuck with me about their work is that there is a kind of truth in it. But it’s illegible. There’s no way to read it objectively. Anyone looking at their images can tell that there’s something there, but neither of them are invested in spelling it out. Below is a conversation I had with the two of them. It’s a combination of an in person interview, and a series of emails.

I came to this conversation thinking, what’s better about this than actually saying what you feel?

Daniel Johnson – I walked out of the department one day, and saw your book Randy. And it struck me how similar you and Dalia work.

Randy West – I thought that was weird. I don’t know if we do.

Dalia Amara – Yeah, I didn’t know until you wanted to pair us together. I thought Interesting, I had never thought of that.

DJ – Randy, tell us about your latest book, I Never Promised You Anything.

RW – Well, what can I say about this book?

DJ – You can start with the title.

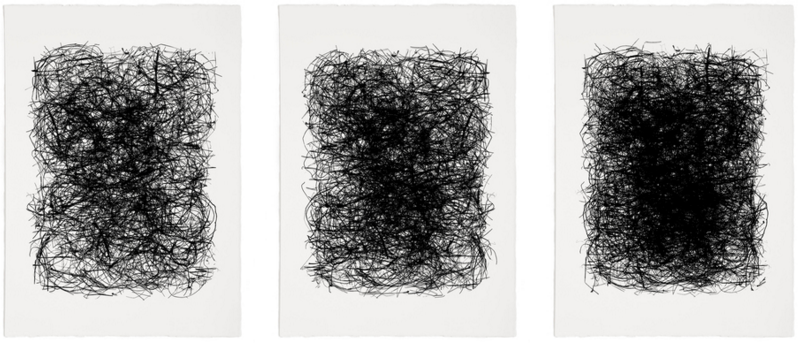

RW – Well, the title pulled it all together. I’ve been scanning things for, oh I don’t know, 10 or 15 years. I Never Promised You Anything was ultimately this series of rose petals that were scanned on the computer.

I Never Promised You Anything

Most photographers, I think maybe even most artists, you just like to look at something. So I was scanning rose petals. Before that I was scanning birds’ nests or objects just to see what it looked like.

I think I say this in the book, I don’t know how many years ago this was, but this was my midlife era and I planted a rose garden upstate. It seemed very cliché and wonderful to do that. I wanted to plant roses. How romantic. And how beautiful. Making them black seemed kind of natural for me because everything that I do, I typically go to the very romantic, the very formal, the very emotional. My work usually has those qualities, and the other thing I tend to do with a lot of my work is that I’ll do something repetitively. Whatever it is that I’m photographing I’ll repeat it again and again and again and again. And then it all comes together cumulatively.

So I scanned the rose petals, and I thought I’d start building them in the computer. I just started pulling them together and layering them. I’d go with the most delicate, white background with the fewest petals falling and then it would just mound into an almost filled up page or an almost filled up image. It’s all coming from a this notion of—How much more cliché can I get? Or how much more romantic can I get? And yet, changing them black makes it a bit more funereal, and the page, it becomes more and more and more black and it just keeps progressing and filling up. A good friend of mine, when she was looking at the work, she wanted the last image to be all black. You know, we show each other our work and kind of critique each other and give each other suggestions, and I remember her saying that to me, and I really respect her opinion. And it made sense, perfect sense, but I remember feeling this little tiny pain inside. I can’t make it all black because then it would be over. Then it would be dead. And there’d be absolutely no hope whatsoever. So the last image has just a little white where there’s just a few more petals to come and I think that had I made the whole entire image solid, it would have been death. Or it would have been over.

The title is funny because my husband—Alan—he and I are always joking and finding really stupid titles for artwork. And we’ll say, “Oh that’ll be a great title for a piece of art.” I have lists and lists of really bad titles or stupid titles. I can’t remember. I think he came up with the title. In the 70s, there was a popular song, a country western song, and it was “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden,” and this work came out of genuine love for building a rose garden. I just thought it would be great to have a rose garden. It’d be pretty. It’d be fragrant. And one of the things I think I’ve talked and written about is that planting rose bushes is not easy. I went out and got a book. I tried to learn how to do it. And I’m kind of hasty. You know, I’ll do things really fast. So I just dug a hole and put the roses in there and watered it and just hoped it would grow. And what I learned is that roses just aren’t that easy. They take a lot of care. Some plants, I guess you can plant. Just make sure it has water and sunlight, and it’ll be fine. But roses can be difficult. So the roses I kept buying, and Alan kept telling me, I was buying them for the wrong climate. I kept making bad choices about the roses. They just kept dying. So we laughed about it. And I thought if it lasts the summer, well that’d be good. At least they lasted a summer. Then we started joking and I can’t remember how it came up. But the song, “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden,” the lyrics of that song, it’s about love relationships. You know, I never promised you anything. Even the lyrics say it, “I beg your pardon, I never promised you a rose garden,” and at that point, Alan and I had been together for 25 years or so.

DJ – I was waiting for this—this is why I wanted you guys to talk. When I saw the book, I thought Randy…this is not about roses.

[laughing]

RW – It’s not! It’s not about roses.

DA – They actually look like ashes.

DJ – Roses are fine, but this is not about roses. I’m trying to see if you gave this a dedication. I can’t find it. But when I saw it, I read it. I read a dedication.

RW – Well, I think what it’s really about. It’s about life. It’s about relationships and maybe when that last page, if it ever did become fully blackened with ink. Then that would be the end of it. Does that mean life is over? Does that mean the relationship is over?

I think what I learned, it look me a long time, and Alan and I learned this together, is that you can’t promise anyone anything.

Dalia, you said you just got married recently. You can’t promise anything, you can only do your best. Your marriage can be as good as you make it. But you can’t really promise. I mean we do. But you can’t really promise anything. We make mistakes. Things change. How can you promise someone something like that? You just can’t. You go into it with the best of intentions, otherwise you wouldn’t, but I think love and life and friendships and all of that—it’s all about doing the best you can. Knowing that you’re going to hurt each other along the way. Knowing that you’re in it for as long as you can stand each other. Or like each other or want to be together. So it’s not about roses, but the roses for me were about love. And I made twelve images, which is like the cliché—a bouquet of roses. And then Paola, who wrote an essay for the book, she brought it into this discussion that twelve, is a calendar year. Twelve months is a calendar year. Every year we go through the same thing again. You hope that your roses come back and bloom again next summer. They go dormant in the winter—hopefully they bloom again. But they don’t always bloom again.

DJ – Maybe they bloom differently?

RW – They bloom differently. And then sometimes they just don’t come back. As a young person, I lost an awful lot of friends to AIDS. There are a lot of promises that you make to friends. It’s not just about love, marriage, or sexual relationships. It’s about friendships too. I think people, I would hope, that we try our best to be good. But we’re not always good. I’ve got some really bad days in me.

[laughing]

And I regret lots of behaviors that I have. But you do your best, and sometimes your best isn’t very good. Paola said one thing that really hit me.

Do you want to look? Great, I offer myself to your sight. You let your eye deposit its look on me; look at what I have to offer. Take heed however: I do not promise you anything, I never promised you anything.

What I offer, so that you may gaze at it, is not necessarily what you seek to see. There is no coincidence between eye and gaze, there is deceit, as Lacan reminds us: “Jamais tu ne me regarde là où je te vois”, you never gaze at me there where I see you. But there is expectation. And if, as in a love discourse, you accept the challenge of this encounter, then perhaps you might be able to find something other than what you expected without even knowing it. Something that shifts us away from repetition and turns me into an opportunity. Something that opens up a new horizon unfolding from the transformation we both share in the act of seeing.

We do want to be looked at. And hopefully, oh gosh, I hope I’m making sense. And not just rambling.

[by email]

DA – It’s interesting to hear Randy talk about as long as you can stand each other, and how it doesn’t just apply to romantic relationships. I feel most of my past is more intense friendships than relationships. I knew Matt and I were meant to be because I could spend the most time with him out of anyone I ever met, and still feel I didn’t have enough of him. With most people, as much as I can like them, I can only stand being around them so long before I want to be alone. With my husband, Matt, I can spend every second with him for days, weeks, months, years, and I don’t tire of him. There was a point in our relationship where I almost felt like we were an extension of each other; we hardly seemed like separate people. And yet, we are different in ways. There are definitely differences between us but at the same time I don’t think I met anyone I feel as similar to.

DJ – No, no, you’re making sense. You’re touching on all the notes I had prepared for myself about why I wanted to talk to both of you.

When I first came to grad school, I remember looking at Dalia’s work and it was challenging. My idea of what photography is was so young. I thought photographs were about life, things that were true. And Dalia’s work was so perfect that it was not about what was in front of the camera. I feel like neither of you are interested in truth as something that can be photographed. I think that both of you use a camera (or scanner) to record things that are not easily perceived, not “true”, but in some sense are extremely true. They’re more true than what’s actually in front of you. I was just really struck by the title of this work, I Never Promised You Anything. Like, how much more vulnerable can you be?

RW – When you go into marriage counseling, if you ever do, you kind of go in hoping that you can work something out, but basically you go into it wanting to know if there’s something to work out. Otherwise, you might decide let’s just go our separate ways. I’ve talked to a lot of people who are either married or in relationships, and there’s this point that you go to counseling for whatever reason, you think you’re going to fix it but fixing it might be separating from each other. That realization of that what you fantasized about getting may not be the reality.

I think that photography for me—I really am interested in what’s in front of the camera because we believe it was there. Even if it’s abstract, it existed. But what you end up getting in two dimensions, whether it’s on paper or on the screen, it won’t be the same. It’s not the same. You kind of have to step back and look at it again, and say, “Well now what do I have?” I don’t know if that’s similar to relationships but there’s a fantasy about what you think it’s going to be and the reality. Sometimes my pictures look better than the real thing. And sometimes, many times, they’re a huge disappointment.

DA – They’re much better in your head.

RW – Much better in my head. That plant is much better than if I would photograph it. That translation that the camera makes can make it better or be a huge disappointment.

DA – Even understanding how cameras work, there are still times when I have an idea that when I go to do it, I realize it isn’t physically possible. Like the angle of the lens. Or that I’m thinking of something that can’t exist. And then I have to change it. Sometimes I think of something that’s just as good or I give it up.

DJ – With your newer work though, I feel like you’re moving further away from that because you’re using Photoshop to do things that can’t actually happen.

RW – Are you creating things in the computer?

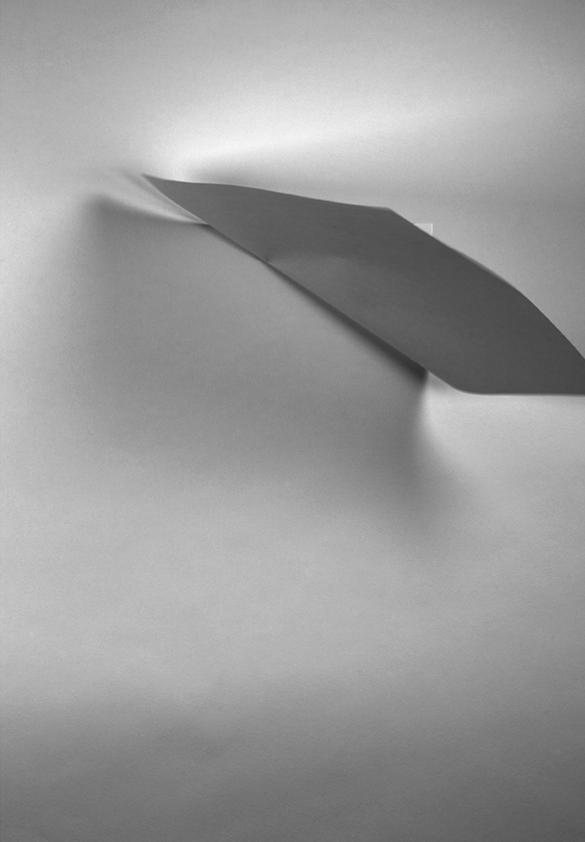

DA – Yeah, sometimes it’s more obvious than other times. The image of the statue where I put some white space in it. There was stuff in the frame that I didn’t want there, but I didn’t have control over it because I shot it outside. There were trees and I wanted it to be white space so I just added it in myself. Or there’s one I did recently––sometimes I’ll rearrange my room or my apartment because there’s something that I don’t feel is relevant in the frame. Sometimes it’s more of a hassle for me to move it, so I just put white space there.

DJ – So you’ve got two projects that you’re working on?

DA – Right now I’m working on Doubles Doubled. The idea was that the objects would be a stand-in for myself and my husband or something desirable. I was really inspired after I got married. We put our registry together and I was looking at all these objects to add to my apartment. Looking at catalogs and websites, and things were so perfect. When you get married, especially when you’re a woman, there’s all this pressure to look perfect and people will go to extreme lengths, the money they’ll spend, and the time and the energy.

DJ – But you did look pretty good at your wedding.

[laughing]

DA – I tried, but I was terrified—I did my own hair and makeup. I was afraid that I was doing everything wrong, and that I really wasn’t putting enough effort into it. But I was thinking of all of this. And how Photoshop is used to make things perfect. Here, I made the vase more shapely, like an hourglass. In one image, I used the waist cincher that I wore under my wedding dress on a balloon. I’m thinking about the humor in how photography is used to make us desire things. And kind of like being the anti-desire almost. I don’t know if that makes sense.

RW – But they are still very sexy and beautiful and sensual. I guess I use photographic technique and then I go in and manipulate something. I work with it, whether it’s layering the files on top of each other or adding something. I don’t have any ethical reason to stay true to the original—I just want to play with whatever I am recording.

I like that I can play. Manipulate things. It’s like if that vase needed to be more sensual and sculpted, then why not do it? It does look like that figure of the corset. Or at least it makes me think of that kind of form.

DA – I also don’t try to make it look perfect. I purposefully had the background squeezed in so that people would know that I manipulated it. It’s like an in-joke. I was thinking of Instagram and how a lot of celebrities or everyday people will Photoshop their photos. Sometimes there are little things like that, and then they become tabloid or blog posts, “Oh, check it out! You can see where she squeezed in her thigh!”

DJ – What role does the body have in your work? Your work is so influenced, or maybe inspired by the presence and absence of bodies. Could you talk about how you ended up using them in your work?

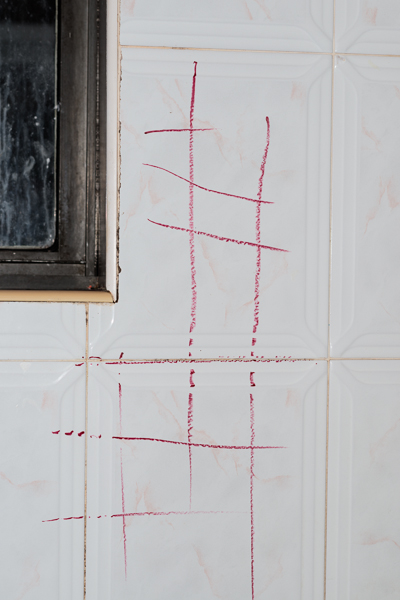

DA – In Death As If, I wanted to allude to the body’s presence while never showing it in order to talk about loss and absence. With the image “Disconnect” I wanted the clay to resemble a tumor—some kind of entity growing on the wood. “Relative Space” I was thinking about surgery, and the violence of cancer treatments, which can often appear more violent to the body than the cancer itself.

“Lipstick Remnants” came about from my own personal experience with my mother’s objects. I’m the oldest of five, and together with my one sister who is close to me in age, we were tasked with going through our mother’s things, in addition to trying to run the household and looking after the rest of our younger siblings. My dad was mostly working and living overseas, so the burden was on us. I was just shy of turning 21, and she was 20. We donated most of our mother’s things. It was mostly just stuff and the charitable route seemed the best way to honor her. But her makeup was too personal, and it couldn’t be donated in any case. It was way too painful to throw away. I felt the strongest connection to it. The shades and colors that didn’t suit me, remained in her bathroom drawers but she had a lipstick that I could pull off. I took it and wore it as a way of preserving its use. Eventually I wore it down and I threw it out, but by that point it was my own, and it was less painful to throw out. I used my own lipstick is in the photo, but the project is about my own death anxiety and body anxiety. It’s more fitting that my own was ultimately used.

In Home Fitness, I started using fragments of the body: my hair, the arm and body of the man, who is now my husband. I wanted to go in the opposite direction of death, and speak of sex and desire. I wanted to reference forms of art that came about before photography like classical sculpture or painting. So much of photography determines our bodily ideals, the Ancient Greeks used statues, and somewhere in the middle there were illustration ads. I wanted the body to be objectified, mysterious, and sexy. I also wanted to speak about the act of wanting to immortalize someone you love in something as concrete as a bronze or marble sculpture.

And in my current work, Doubles Doubled, I wanted to continue exploring the concept of ideals with not just the desire of the body but also the desire of things themselves. I am interested in how the objects can be used in place of the body, and speak about the manipulation used to build these ideals but I am also interested in the appeal in owning things. There is also an added humor that can be evoked in combining the two, such as the absurdity of putting a waist cincher over a balloon and calling it “Hugging a Balloon.”

I find bodies fascinating for our want to control them, and how they can also function beyond our control. We can control them consciously and unconsciously but when we can’t, we feel betrayed. So much of our time is spent trying to master the body, how we think, look or act. They’re also a reflection of our interior, our mental state and our inner biological health. We see the body as a home to our psyche. In this way, domestic spaces and the body are both perfect metaphors.

DJ – This idea that there is a truth behind photographs—like people who actually get angry. That’s just absurd to me. At the beginning of the day, photographs start off as a lie. You’re taking something 3 dimensional and you’re reducing it to 2 dimensions. That translation is destroying all kinds of information. You can’t actually represent an object the way it should be represented. You know, models that are good models they only look good because of the way they photograph, not because they look like that in person. Being in NY, I think we’ve all seen someone famous in the street and it’s like who is that unfortunate looking person, and then you realize who it was later.

RW – They just photograph really well.

DJ – The way you stand, the way you shift your weight, the type of lens, where the camera is, how you place your hand, there’s just all these little tricks that most people are unaware of. Nobody actually looks like what they look like when they’re photographed.

RW – I hate pictures of me.

[laughing]

Like, “Do I actually look like that?” Yeah I guess I do.

DA – I think that’s also why I’m usually interested in mirrors too. Because the way you see yourself and the way you’re in photos can be so different.

DJ – Yeah.

DA – Like they do different things.

DJ – I think I’ve noticed that seeing myself in video… seeing myself in a mirror, it’s always from the same perspective. The mirror is always right in front of me. It’s always in the same position. And I’m always just straight on, that’s all that I see. But if I see myself in video or in photographs, I can see myself in ways that I’ve never seen before. There’s that Sontag quote that I mentioned in another post. She talks about photography as being violent because you’re seeing someone in a way that they’ve never seen themselves.

DA – One of my more traumatic experiences of puberty involved mirrors. When I was born and for most of my childhood, I did not have a “bump” on my nose. With puberty, I inherited my mom’s very German nose. I was so used to seeing myself in mirrors straight on, and then one day we were in a department store trying on clothes, and I was surrounded by mirrors on all sides. I was horrified, I couldn’t recognize myself. All along, I was not aware of what I now looked like in profile. All the previous photographs of me in profile had a very different nose. I felt betrayed that people had this awareness of what I looked like much sooner than I did. Eventually, when it happened to 3 of my 4 siblings, as the older sister, I could point it out and laugh with them. We made sure to tease our youngest sister that never got it, we told her she was adopted.

DJ – I think both of you are interested in domestic life. Could you talk about that a bit? Would you admit that? Do you think of your work that way?

DA – I admit it. But it’s one of those things where if I say it, I know they might start to get ideas about the work that I may not like—just being a woman, it’s so loaded. I try to use domestic life and objects but not be overly political or cliché about it.

DJ – How do you even negotiate that space? It’s interesting that your work looks nothing alike, the themes, yes, but I don’t think anyone would say “Dalia and Randy, they are similar photographers” but the themes are there.

RW – I never really saw myself as being interested in domestic life though.

DJ – So when you think of the bird’s nest, that’s a home, the rose garden…

RW – I can see where you pull some of that together. It’s just not something I think about. If anything, for me it’s about whatever the thing is that I’m recording. I’m getting more and more interested in removing or concealing information. Like, whether it’s making, you know, twelve pictures of rose petals that eventually go from a very empty palette to one that’s very full of ink. You know, like very full—fill the page up with black ink—or if it’s, um, uh with the bird’s nests it’s the same thing. It’s, like, the first view of the fibers are really kind of readable and, uh, sparse and they get denser and denser and denser until the top totally fills in the center area of the image where it becomes very dense, black ink with newer work right now it’s trying. I think that in my mind, I have too much stimulus and in order for me to calm down, it takes a process of removing or concealing. Just quieting the picture. I can get really carried away with all of these little formal qualities, but the one that ends up being the most successful is the one that’s the quietest.

DJ – See, I think what you just said reminds me of Dalia. For Randy to say that he’s interested in taking things away, like, physically I guess I’ve always recognized that as one of the foundations of Dalia’s work—she always wants to say things but doesn’t want to actually say it.

DA – Well, with my earlier project, I think people had a hard time with it because they didn’t feel it was personal enough or that it was too cold in comparison to the subject matter, but I think that the work was really about my anxiety towards death because my mom passed away at forty-five years old from cancer and we didn’t expect it. We thought she’d outlive our father. She was a lot more physically healthy in her lifestyle—we just didn’t see it coming. Even when she was diagnosed there was a period where we thought she was in the clear and suddenly it just came back and it was everywhere and metastasized and it was too late to do anything. I could barely process what was happening. I think people expected images of my family. When other people would do projects about cancer, they’d take actual photos of the person or their objects, but mine was about this fear of confronting that and about feeling this loneliness and this anxiety and it was really more about me than my mom.

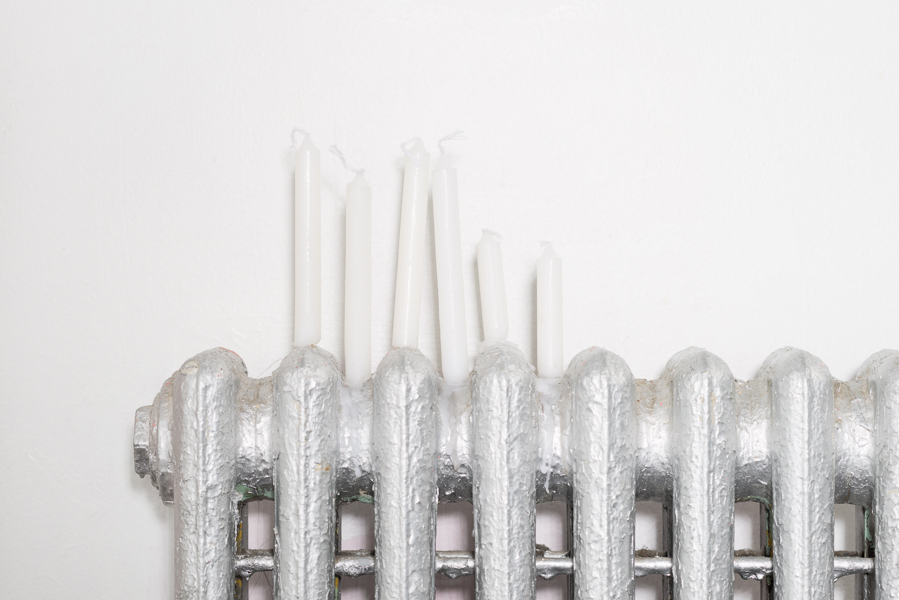

At the time, I didn’t really have a whole lot in my apartment. I didn’t make it a home, I was just in school. I have roommates and we just kind of lived in this bare but interesting place. When Hurricane Sandy happened, we spent a lot of time inside, it was like kind of being trapped. A lot of trains weren’t running, a lot of things were closed. I was just sitting in my room and staring at things. Like you do when you’re depressed. You’re not reading or watching a movie, you’re just sitting there and starting at your place. So I started to draw inspiration from that, and I wanted to incorporate some cliché elements of death, like the candles or like the draped velvet but also do it in an unexpected way.

My mom passed away in our house. The presence of her, slowly dying was not something we could escape, so I wanted to reference that too. When the domestic place stops being something comfortable and relaxing or inviting, and it just becomes violent and uncomfortable. I do feel like there is that anger, violence in the images. Maybe in that way they’re successful.

DJ – It’s there, but it’s it’s understated. You know, it’s kind of like you’re whispering, and the wind is blowing, and the moon is out, and it’s just kind of bleak. Not the work is “dark,” but it kind of is.

DA – I still feel vulnerable when I show my work. And sometimes scared of how much it may say about me without me realizing it. In some cases, maybe the viewer can only see what they see because they can relate in some way. Then we’re both vulnerable, and it seems less terrifying.

I’ve also experienced instances where viewers don’t see or read me at all in my own work because they can’t see past themselves. I did a studio visit with an artist who hated Death As If because the only thing it reminded her of was her father’s violent murder. She read my work as someone being kidnapped, tortured and killed. She could only read her own trauma.

DJ – What does it mean to be vulnerable?

I sent someone this quote from Toni Morrison the other day. I think it’s applicable to your work. Or maybe why you make work. Replace love with art.

Let me tell you about love, that silly word you believe is about whether you like somebody or whether somebody likes you or whether you can put up with somebody in order to get something or someplace you want or you believe it has to do with how your body responds to another body like robins or bison or maybe you believe love is how forces or nature or luck is benign to you in particular not maiming or killing you but if so doing it for your own good. Love is none of that. There is nothing in nature like it. Not in robins or bison or in the banging tails of your hunting dogs and not in blossoms or suckling foal. Love is divine only and difficult always. If you think it is easy you are a fool. If you think it is natural you are blind. It is a learned application without reason or motive except that it is God. You do not deserve love regardless of the suffering you have endured. You do not deserve love because somebody did you wrong. You do not deserve love just because you want it. You can only earn – by practice and careful contemplations – the right to express it and you have to learn how to accept it. Which is to say you have to earn God. You have to practice God. You have to think God–carefully. And if you are a good and diligent student you may secure the right to show love. Love is not a gift. It is a diploma. A diploma conferring certain privileges: the privilege of expressing love and the privilege of receiving it. How do you know you have graduated? You don’t. What you do know is that you are human and therefore educable, and therefore capable of learning how to learn, and therefore interesting to God, who is interested only in Himself which is to say He is interested only in love. Do you understand me? God is not interested in you. He is interested in love and the bliss it brings to those who understand and share the interest. Couples that enter the sacrament of marriage and are not prepared to go the distance or are not willing to get right with the real love of God cannot thrive. They may cleave together like robins or gulls or anything else that mates for life. But if they eschew this mighty course, at the moment when all are judged for the disposition of their eternal lives, their cleaving won’t mean a thing. God bless the pure and holy. Amen

DA – When I’m working on an image, the first thing that’s important is if I have an emotional reaction to it or if it comes from my own feelings. I place equal value on intuitive, irrational emotions and rationalized intellect. By putting my work out there, I’m then asking for an emotional response from the viewer. I hope for a strong response, negative or positive—I would be more bothered by a neutral uninterested response.

I use a series to layer emotions, the images build and add upon one another. I find my work is viewed best sequentially within a given series. The images are often weaker when divorced from each other. Maybe 4 from the same series can work together but definitely not less.

I agree, you can replace love with art in that quote, and it would still ring true. Art is a lot of work, it’s hard, it’s an emotional rollercoaster, and it’s an unattainable ideal.

To be vulnerable is to place yourself in an intimate position where you are sharing who you are, and are open to acceptance or rejection from others. I think most importantly you’re not attempting to control those reactions. I know I highlighted more negative reactions to my work in the interview so far but there are positive ones too. It’s not all bad, and when it is bad, you just have to keep making the work anyway.

After I worked on Death As If, Matt (my now Husband) and I moved in together. Before that neither of us felt domestically inclined but together we’re suddenly interested in buying a couch, rugs, and making a home. I wanted to move away from death, and focus on domesticity in relation to sex and desire. My work is tied to my emotions so changes in my life prompt me to move in different directions.

RW – I love hearing this. Hearing how you reacted to death within your family, and especially your mother. And then thinking of how I did it when I was in my twenties. Just out of graduate school, I was losing a lot of friends, a lot of lovers. A lot of people I knew were dying from AIDS, and I would go out to the beach because I grew up in the middle of the country in Indiana and the ocean was this, like, wonderful, amazing thing that I had not really experienced as a kid. I mean, I’d been to the ocean so it wasn’t totally foreign, but it was just a new landscape for me or a new seascape. So as I was losing friends, I started photographing these surfers and people out in the water. You know, these little tiny figures. And then when I would print them, I would print them very gray and then I would rub charcoal over the print. More and more and more almost unreadable so that you could maybe even not see the ocean and the figures swimming in the ocean. I took a different approach—I was trying to conceal information and to remove it. Maybe you won’t see it, and if you don’t see it, that’s okay. We don’t have to talk about it. We can ignore that this is happening.

One of the things that worked out to my advantage when I showed that work in the late ’80s early ’90s, was that it was shown in Los Angeles where you would maybe be outside in the bright sunlight and you would walk into a bright gallery, and sunlight and everything is so bright and white. And the white walls—that was the traditional kind of space for a gallery—you would come in and you would see these little gray rectangles on the wall. And a lot of people, because your eyes didn’t register, you really didn’t see anything. You saw a gray slab. And a lot of people would just walk away. They’d walk away and just be like, “Oh great, rectangles on the wall.” And think, “Oh this is minimalism.” But if you gave it a minute or two, you’d start to see little tiny figures in the seascape.

For me it was about slowing down. I’m not sure what you’d say you felt when your mother was dying. I think maybe we all deal with emotions differently. You know, whether it’s with the rose book and roses or love or being in love or out of love or the loss of people. I think my true self is an incredibly emotional person, but there’s this surface that I’ve learned to put on which is to be unemotional because the emotions are way too heavy. They’re way too cliché. Like, no one actually wants to hear your problems—no one can really feel it. My mother is still alive, so I don’t know what it’s like to lose a mother. But I can hear you talk about what it’s like losing a parent, and I can imagine maybe what that might have been like. I can empathize but I don’t know what that feels like. We’re all probably dealing with emotions differently. My emotions have always gotten me in trouble when I’ve let them be way too obvious. I don’t know if it was from childhood, but I’ve always felt better when I could pull the emotion way down—like making rose petals into one black sheet of paper, or making seascapes into really gray slabs of almost nothingness. The emotion is a real quiet emotion. There could be sadness underneath it all, like when I look at this work. I haven’t seen it since you graduated.

I love these photographs because there’s a lot of humor in them. I remember thinking they’re funny, but then when I hear the story and I look more at them it’s like, “No, there’s a lot of sadness and anger in them.” I mean, just the rope on the window, that’s—I’m laughing but I’m not—I’m in a state of confusion, which I guess is a good state. It’s being interested enough to be confused. What’s going on in here?

DJ – What I’ve always liked about your work, is that it doesn’t give you an answer. It would have been easy for her to be like, “Hey guys, my mom died. I’m sad.” Take a bunch of selfies. But Dalia didn’t do that. She worked really hard to produce these images and to learn how to talk about death and anxiety.

I’ve kind of been here for the entire ride, so I’ve had the inside scoop. But when you first started making this work, you didn’t really talk about your mom dying.

DA – My first critique with Penelope I did, but it made it difficult for people to read the work. It forced me to be more personal, and that wasn’t the direction I wanted to go. So then I thought…

DJ – Wait, wait, I want to talk about personal because what does that even mean? You’re making work about your mom dying. How could you not make it personal?

RW – I don’t know that this is about her mom dying, and I don’t know that my book is about me and Alan. That’s where it comes from.This is the time that it was made. If you were to look at my seascapes from the late ’80s you would not think AIDS. AIDS wouldn’t enter your mind at all. They would just be dark, gray seascapes. But it’s what made me make the work.

I think what Dalia’s pictures are for me, they’re very poetic pieces that give off an emotion or a feeling and I can either find humor in them or I can find quietness or I can find some romantic, graceful qualities in them.

The thing is if I can feel something. If I can feel the candles. If I can feel the candles on the radiators and have some kind of reaction to that—it’s a much more successful image than if you had made something that was about the death of a parent. Unless you wanted to document death. But that would be a different artist.

DJ – That’s what I like about you guys. The work isn’t just one thing. It’s like you make work to communicate these things you actually can’t articulate. Which is what’s so incredibly difficult but also elegant about it. How can you say how you feel when your mom dies? And how can you say what it feels like to plant a rose garden upstate? Like, what do those things feel like? You can’t just say it.

RW – And actually if I had made a body of work about planting a rose garden it would probably be pretty bad or pretty boring.

I think that what you and I would like to do, or myself, I’d like the viewer to get to the place where they can feel something that’s––one of the things you did say in your email was that the thing that you can’t really articulate, the minute you describe something you kind of kill it because it’s been described too much with words and you’d rather just look at something and have an emotional reaction to it.

DA – I didn’t want my pictures to make sense necessarily, completely. I think confusion is fine. You know, people have said “What does duct tape have to do with your mom passing?” or “You know I find this humorous, isn’t that like troubling to you?” Part of it was trying to feel like I was in control but also realizing that, you know, to feel like we’re in control is kind of silly. We’re not in control so in that case they can be funny because sometimes they were just failed attempts or made to look like that. Someone said, “It looks like someone wanted to hang themselves but there’s no way you can hang yourself with the rope like that.” I was like “well, you know sometimes I might feel like killing myself but I don’t want to actually kill myself.”